Whilst searching for a photograph of West End pharmacist J.P. Davies, I discovered a little treasure trove of memoirs of the local Air Raid Precautions (ARP) group. A storage box contained not only a photo of J.P., who was the Chief Warden, but also other photographs and ephemera, including a minute book of the West End ARP committee.

These were donated by Elsie Dunn, who along with her brother Douglas, lived in Little Jane Street and was a member of the ARP. This blog looks at West End in World War 2 based on this material.

1939 – The outbreak of war

Throughout 1939, the clouds of impending war hung over Europe. Rearmament rapidly increased and frantic diplomatic efforts were made to prevent the outbreak of hostilities.

The Commonwealth Government began to build up Australia’s armed services, but relied on the states to manage internal security. This included preparation for air raids. The world had been horrified by the devastation wreaked during the Spanish Civil War a few years earlier. The attack on the Basque city of Gernika in 1937 demonstrated the likelihood of heavy civilian casualties from aerial bombardments in future wars.

As well as the threat of war with Germany, Japan’s policy of southern expansion, or nan′yō, was of great concern in Australia.

Key personnel such as police, fire brigade, and ambulance members began air raid response training. From February of 1939, exercises were held at the Kelvin Grove Defence Reserve. They were based on the approach to Air Raid Precautions (ARP) that was being followed in Britain.

On the third of September 1939, following Germany’s attack on Poland and the subsequent declaration of war by Britain, Australia also declared war.

Formation of ARP groups

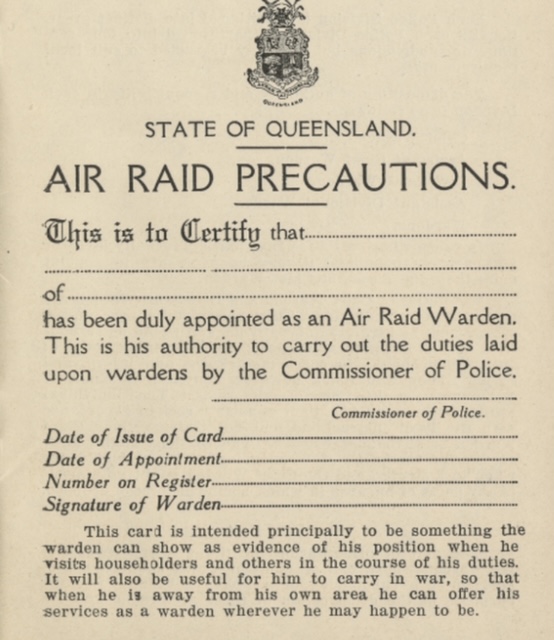

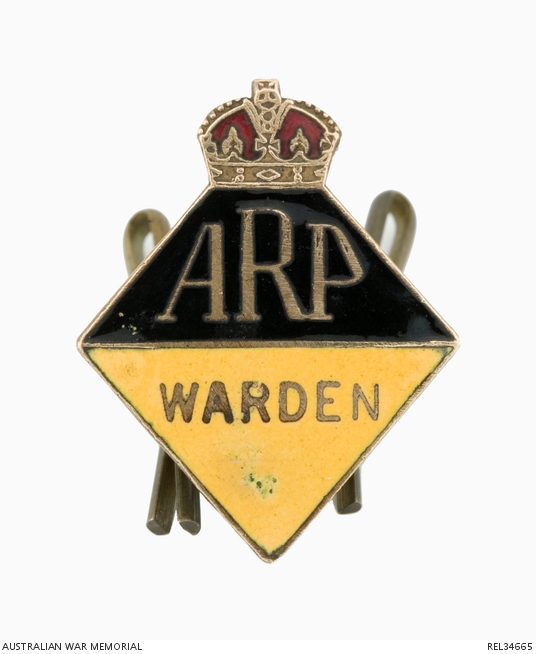

The Queensland Police established local Air Raid Precautions (ARP) committees. Well known local chemist J. P. Davies took on the role of Chief Warden for the West End District.

In October, Davies and Sergeant Allen of the West End police held a public meeting at the Lyric Theatre to recruit volunteer wardens.

At the end of the year, the Queensland Parliament passed the Air Raid Wardens Act. Wardens were to be appointed by the Police Commissioner. During air raids, they were authorised to enter any place and arrest anyone trying to prevent them, and also had all the powers of a police constable.

1940 – Australia mobilises

Australian’s 6th Division left for Europe in early 1940, but France fell to the Germans before they could be deployed. By early 1941, both the 6th and 7th Divisions were fighting the Italians and Germans in North Africa.

In West End, the drive for sufficient air raid wardens continued. Men outside the military recruitment ages of 20 to 40, and those in reserved occupations, formed the bulk of warden numbers. Recruitment of women did not commence until early in 1942.

By June of 1940, 2,000 wardens had been enrolled in Queensland and were in training. They were assigned to the subdivisions of their local Committee area where they lived. Wardens’ roles included surveying their allotted areas to determine who was living where, and identifying people who would need assistance in the event of an air raid.

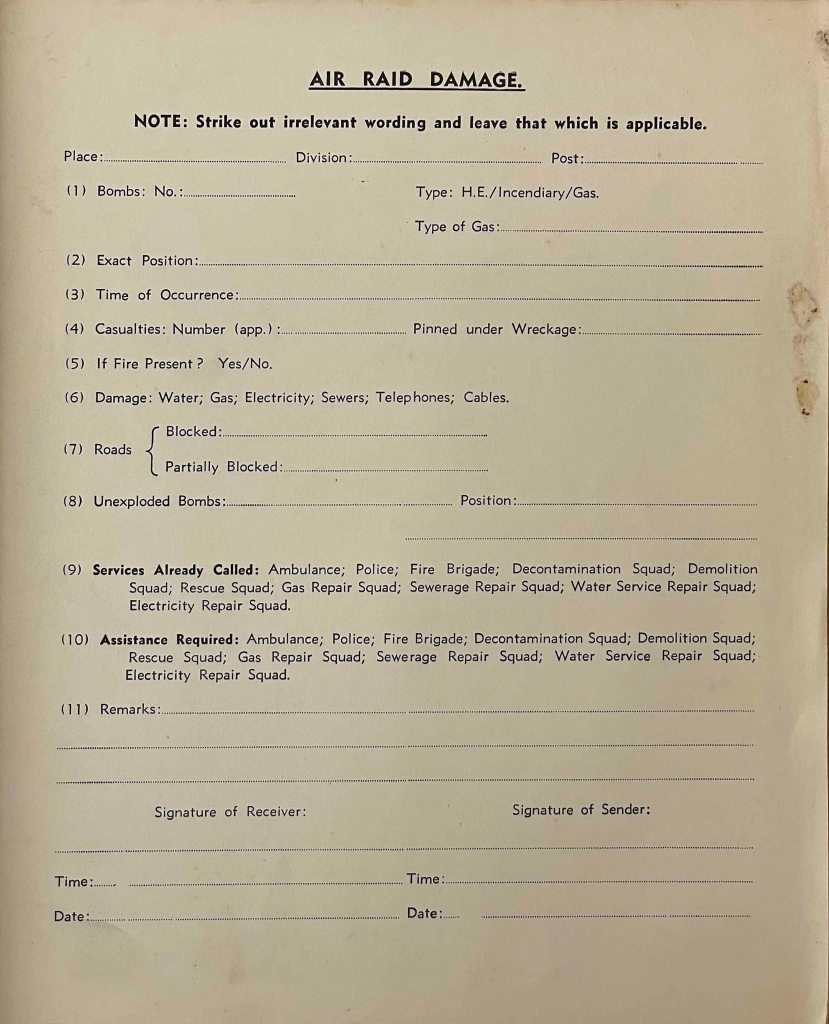

During air raids, wardens were to perform first aid and contact emergency services as required to advise of injuries and fires. At this stage, locations for air raid shelters had been determined, but none had been built to avoid panic. The war was still very distant from Australia.

In September, the blitz began in Britain, with sustained heavy bombing of cities. In the same month, Japan joined the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, further raising the prospect of war in the Pacific.

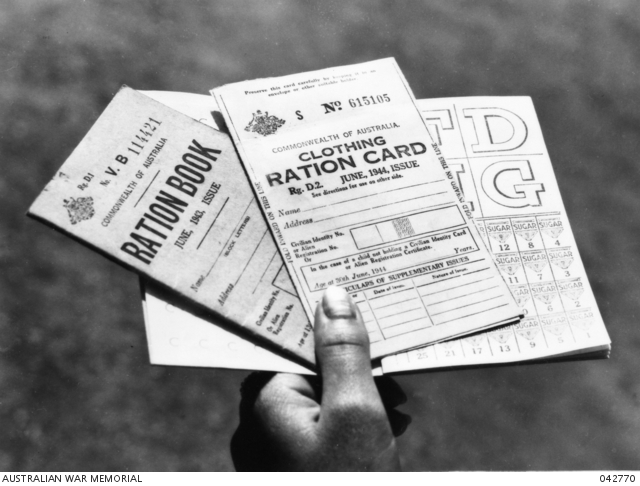

Petrol rationing

Australia relied on imported oil, and tankers under British control were being diverted elsewhere, causing our reserve stocks to plummet. The government introduced petrol rationing in September and further tightened allocations in 1941. Road traffic dropped by a round 60% as a result.

The complex scheme was open to rorting. In 1944, West End petrol station proprietor Thomas Cleaver was found to be running a scheme in which he purchased ration tickets on the black market. These enabled him to sell petrol to people without tickets. He charged them 8 shillings a gallon instead of the regulated two shillings and sixpence (5.5 cents per litre). Cleaver was sentenced to two and a half years with hard labour.

The West End ARP group

By the end of the year, the West End ARP group was in operation. In December, J.P. inspected his wardens at posts that had been selected around the district. These were locations where the wardens were to assemble when an air raid alert occurred. One was Peters’ Arctic Delicacy factory, today part of the West Village development, where a first aid post had been established in the basement.

1941 – Australia at war

Throughout 1941, tensions mounted in the Pacific. In July, Australia sent its 8th Division to Malaya instead of to the Middle East, to assist in defending an anticipated attack by Japan to obtain oil supplies from Sumatra.

Motorcycle dispatch riders

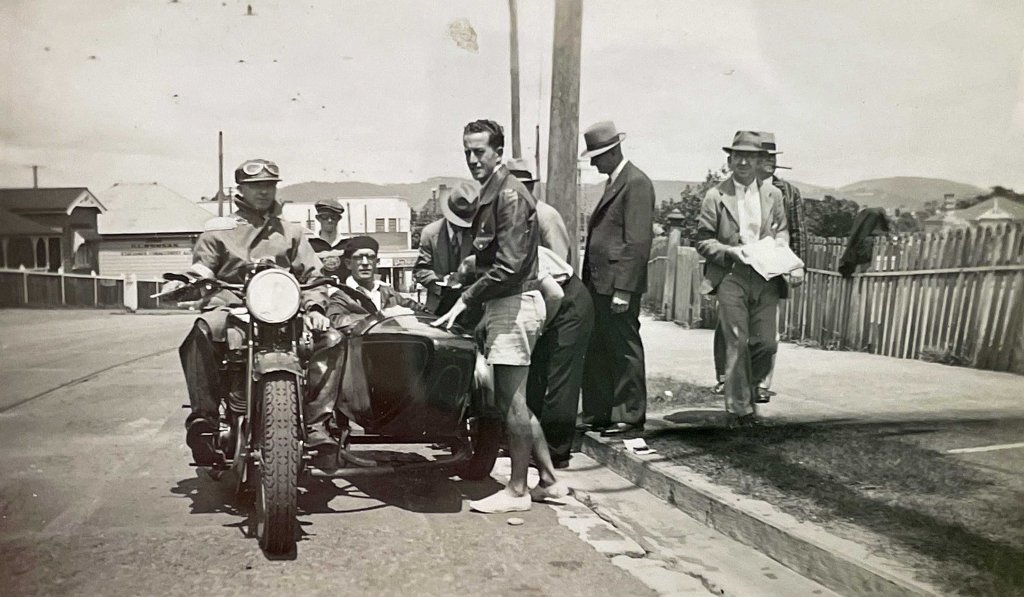

Numerous photos in the Elsie Dunn collection are of motorcyclists in front of the West End State School.

Hospital authorities were concerned about the ability to communicate with first aid centres during air raids, as there was a distinct possibility of the telephone network being damaged. A call was made for volunteer motorcyclists to act as dispatch riders.

In January of 1941, the first trial was held. By mid 1942, there were over 100 motorcyclists taking part.

Black out trials

In August, the civil defence authorities decided that it was time to test blackout processes. Wardens patrolled the streets during the blackout, and The Courier-Mail reported that the only casualty was to warden R. Moloney of Highgate Hill, who was attacked by two dogs while investigating a light on a property.

The one hour exercise on the Southside was followed by a two and a half hour blackout for the whole city in September. Further blackout trials were held from time to time.

The minute book in the Elsie Dunn papers held by the State Library of Queensland1 commences with the November 1941 meeting of the West End ARP committee, held at the School of Arts. There was a report on a recent black out trial in which 149 of the West End wardens participated.

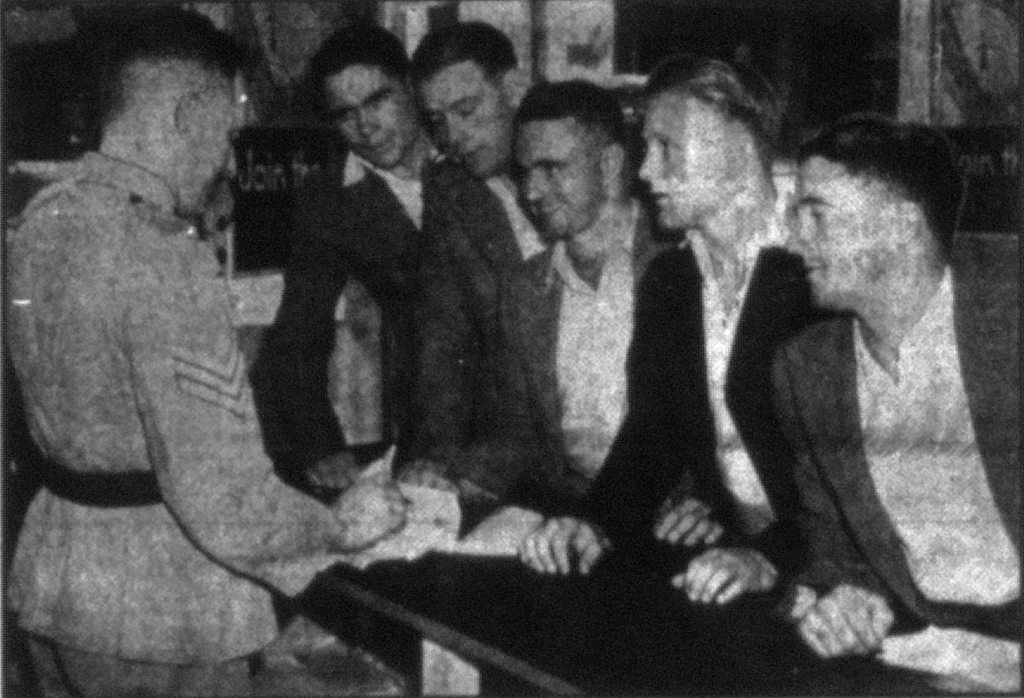

Recruitment for the armed forces continued to ramp up. In October, the Courier-Mail reported the recent enlistment of five Cobbers in Arms, all from West End and Highgate Hill, who had gone to St. Laurence’s College together.

All five served together in the 2/5th Armoured Regiment, which for various reasons was never deployed outside of Australia. They were discharged by 1946.

On the 8th of December 1941, Japanese troops invaded Malaya, in coordination with attacks at Pearl Harbor, the Philippines, Guam, Wake Island, Thailand and Hong Kong. Australia rushed hastily trained recruits to Singapore to shore up defences.

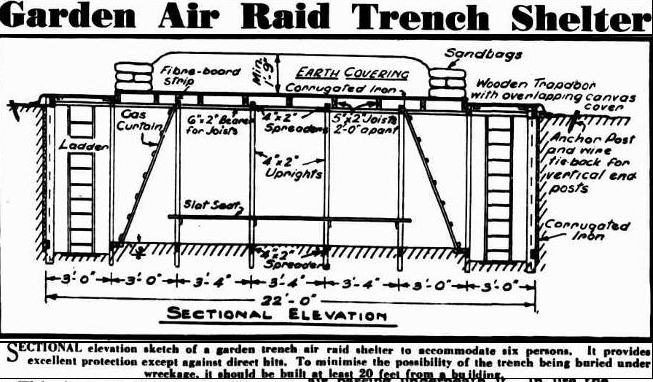

Home air raid shelters

Residents were now encouraged to build back yard air raid shelters. A demonstration shelter in Musgrave Park assisted householders with their planning.

The December West End ARP meeting discussed the West End sand dump and the need for residents to collect their allocation. The sand was to be used in home made pillows used to extinguish incendiary bombs.

Recruitment of women

At this meeting, Sergeant Allen of the West End police talked about the urgent need to recruit more women, as there was a serious lack of wardens during day time when most men were away from home at work. Only 3 women had volunteered in the West End Division, although by March, 1,100 female wardens had been trained around Queensland.

Women wardens were only on duty in day time.

Things get serious

With the Japanese rapidly advancing down the Malayan peninsula, on the 27th of December, Sergeant Allen called a special wardens’ meeting at the West End Police Station. Allen was alert to the danger of air raids, as his own mother was living through the blitz in London.

He called for a check of all first aid posts to ensure that there were stirrup pumps, 2 way nozzle hoses, shovels and gas masks. Wardens’ houses were to have an “ARP Warden” sign at the front.

Sergeant Allen urged all wardens to wear their badges. A document “Hints for the guidance of Air Raid Wardens” from early 1942 intimates that wardens had previously been ridiculed when they wore their badges, as the threat of air raids hadn’t been taken seriously by many.

1942 – Crisis

Singapore fell to the Japanese in February of 1942, and Australia lost one quarter of its overseas troops, killed or taken prisoner. Less than a week later, on February 19, Darwin was bombed for the first of 64 times. Many thought that invasion was imminent and this was being debated in Japan.

All this came as a great shock in Australia. Singapore had been developed by Britain as an “impregnable” naval base at the staggering cost of £60M, and Australia’s defence strategy was based on a naval repulsion of any attack at Singapore.

Schools

The Queensland Government decided that schools along the coastal belt and in the far north would not open after the summer holidays, affecting almost 100,000 children. The Education Department expanded its correspondence classes, however schools started to re-open from mid February after slit trenches or other suitable shelters had been provided.

My father told a story of how as a 13 year old schoolboy at Junction Park State School, he and his classmates were put to work at digging slit trenches. They far preferred this to sitting in a classroom!

Not long after they were dug, the trenches at West End State School were filled with storm water and then turned to mud.

Air raid shelters

After an urgent appeal for bricklayers late in 1941, air raid shelters began appearing along city streets.

Employers were asked to prepare shelters in suitable locations. For example, the Queensland Can Company factory in Vulture Street had a shelter under its crown seal building in Turin Street.

Around Brisbane, 235 ‘pillbox” style shelters were constructed with the intention of reusing them after the war with the walls removed as park and bus shelters. Only 21 survive today.

ARP committee meetings

The first West End ARP committee of the year was held in January at the West End State School, and Police Inspector O’Driscoll attended. He commanded the South Coast District that extended down to the NSW border. Florence Michael O’Driscoll had literally been dragged into prominence as a constable in 1914 when he was awarded a Medal for Merit after doggedly pursuing a stolen sulky and was dragged along the street after grabbing the reins whilst being assaulted by the thief.

Perhaps there were mutterings at the meeting about the fall of Singapore, as he is recorded as having admonished the meeting saying that

“it was not the time for recriminations and if they were going to blame the Empire for any mistakes made, they would have to go back to the days of Adam“

O’Driscoll went on to stress the need to select a suitable warden post to be used as a mortuary, as overseas experience had shown that this was essential. He said that identification discs should be worn by everybody, especially children, in case of injury during an air raid. Bracelets were not encouraged due to the possibility of loss of a limb. The Queensland Government manufactured discs for school children and others had to organise their own.

Wardens were to conduct a census of homes in the area to determine which could accommodate families whose houses had been destroyed in air raids. He finished by telling the assembled wardens that it was “not time for the carping critic“.

The February meeting was attended by Police Commissioner Carroll, who urged wardens to build backyard shelters as an example to others.

Monthly meetings of West End wardens continued through 1942. The meetings kept wardens up to date on developments, allowed feedback on problems such as inadequate street light shielding, and also included training sessions.

The number of women involved had steadily increased. Davies informed the June meeting that 126 male and 35 female West End wardens had participated in a recent black out trial.

In July, the West End ARP Division held a display afternoon in Davies Park which included demonstrations of fire fighting and first aid.

Wardens were meant to be issued with an armlet, badge, whistle, rattle, steel helmet and respirator, but the problem of shortage of equipment repeatedly arose. Inspector O’Driscoll advised wardens that respirators were irreplaceable and some had been damaged when children were allowed to play with them. Helmets were also in short supply.

“Brown-outs” and rationing

In late 1941, permanent “brown-out” regulations requiring restricted lighting had been introduced by the Commonwealth Defence Committee. The restrictions were progressively tightened through 1942, with the most stringent requirements introduced in June.

With greatly reduced street and vehicle lighting, the number of road accidents increased. A few days after the new regulations came into effect, a Highgate Hill man died after being hit by a tram in darkened Stanley Street. Brown-outs finally ended south of Rockhampton in July of 1942.

Rationing of clothing, tea and sugar was introduced from mid 1942. Later, butter and meat were added. Rationing was progressively removed after the war, with the last item, tea, freely available from July 1950.

June of 1942 saw the Battle of Midway that halted the Japanese advance across the Pacific. Over the period from July to January of 1943, Australian troops doggedly pushed the Japanese back along the Kokoda Track. The fall of Port Moresby, and subsequent increased air raids in Australia, were avoided.

Adopt a POW scheme

In August, the Red Cross inaugurated a scheme in which volunteers would collect donations from householders in a street. If they reached a level of £1 a week, a street sign was erected and each house received a gate badge. The Red Cross used the money to send relief parcels to prisoners of war.

Some long term local residents recall these, and a street sign remained in place on Colton Street, Highgate Hill, for decades after the war.

Towards the end of 1942, the West End wardens’ meetings were changed from monthly to two monthly, although Davies instigated an hour long practice session once a month.

1943 – The tide turns

By late January of 1943, the allies had defeated the Japanese forces that had invaded New Guinea six months earlier, and the likelihood of further air raids greatly diminished.

At the February meeting, Inspector O’Driscoll urged wardens to maintain interest as the country was “still passing through a crisis“. However, month by month attendance dropped and over 100 wardens had resigned by February. His announcement that 250 additional stirrup pumps had been delivered was met with applause.

In May, there was a tragic reminder that the war could still come close to Brisbane. A Japanese submarine sank the brightly lit hospital ship AHS Centaur off Moreton Island, with the loss of 268 crew and members of the 2/12 Field Hospital.

By October, O’Driscoll was using a carrot and stick approach to maintain enthusiasm. He warned that there was risk of attack by Japanese suicide squads, and also suggested that ARP groups start developing the social side of the organisation. One attendee mentioned that many West End shop keepers had removed the protection from their windows in violation of the security regulations still in force.

By late 1943, hastily constructed air raid shelters in backyards and public spaces such as schoolyards all over Brisbane started to become a health concern. Even with corrugated iron roofing, after rain they often had water in them where mosquitos bred. Some collapsed altogether after heavy rain. Householders were advised to fill them in if they had become breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

The year ended with an ARP meeting at the Lyric Theatre in Boundary Street with a very low turn out, despite the appearance of Victor the Great, a ventriloquist.

1944 – The beginning of the end

During 1944, the US forces continued their island by island drive towards Japan, whose defeat now seemed inevitable.

With large numbers of men in the armed forces, many women had entered the workforce in jobs previously unavailable to them. A group of local women saw the need for child care facilities and lobbied the mayor, John Chandler, for assistance. The mayor agreed to the use of the School of Arts building, initially free of charge, and the Kurilpa Child Care Centre, still in operation today, was born.

As the year wore on, the wardens’ meetings became less frequent. In April, Inspector O’Driscoll gave “a splendid interpretation of Kipling’s immortal Gunga Din“. At a June meeting of Chief Wardens at the Roma Street police station, there was speculation that use of the organisation for other community duties could be possible in the future.

Towards the end of the year, wardens spoke of how after five years of working together, they would miss the many friends they had made.

1945 – Peace

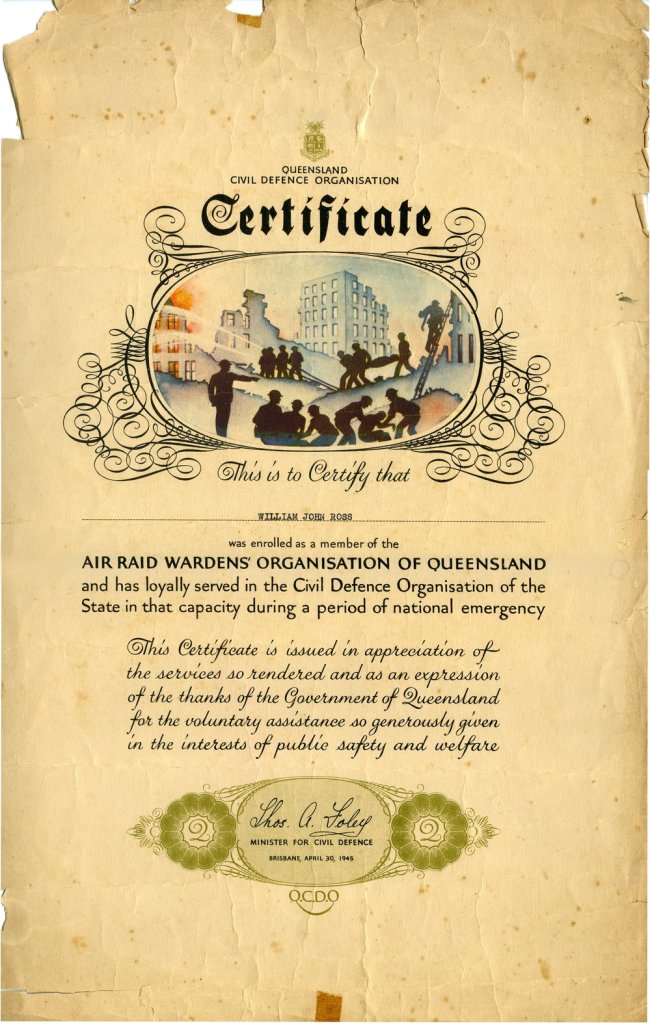

The ARP organisation was formally disbanded at the end of April. In May, J.P. invited wardens to his home to plan a celebration for wardens and their families.

The event was planned to be held at the Rialto Theatre and was to feature entertainment and the presentation of participation certificates, although no newspaper report of the event seems to have been published.

Following the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August, Japan agreed to surrender. The fate of many missing Australian service personnel became known after the surrender.

Throughout the war, and for some time after, the Courier-Mail published daily photos of service men and women killed, injured, missing or taken prisoner. Here’s a small sample from Kurilpa. My post “Lest We Forget – Highgate Hill” takes a wider look.

Thoughts of maintaining the ARP organisation for civil defence did not materialise. The Queensland Civil Defence Organisation was re-established in 1961 to deal with emergencies in the event of a nuclear war. This eventually became today’s State Emergency Service.

References

Most references appear through the text as hyperlinks.

- Dunn, E. (n.d.). Elsie Dunn Papers. State Library of Queensland

© P. Granville 2024

Once again Paul, thanks for this story, I love your outstanding research! Here’s an Air Raid whistle that I saved from the old Newmarket police station on the northside before it was moved and then burned. https://historyoutthere.com/2019/11/08/archaeological-emergency/ It featured in a couple of stories, but neither to the fantastic depth of this story of your’s. https://historyoutthere.com/2019/11/15/history-corrected-after-100-years/

LikeLike

Thanks Harold. I know my posts are too long for most readers. Your’s are a far better length and always interesting. We had one of those whistles and a helmet at home that had belonged to my grandfather. I think my parents threw them out when they moved home years ago.

LikeLike

Fantastic read – thank you so much.

Not sure if you are able to help me or could point me in the right direction, I live in The Village Apartments (old Tristan’s soft Drick Factory) I’m on the Body Corporate and we have a newsletter that we produce for the owners. I would like to find out some history of the House Conspiracy – long before it’s present artists use. I’m thinking like when it was built, who built and who lived in it first – what was their history coming to West End etc.

Can you point me in the right direction – I love old building and history but don’t know how to find info – on the net is all modern info but I’m trying to look at the beginnings.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Shane thanks for your comment . If you’d like to use the ‘contact me’ feature of my blog , I’ll be able you email you what I have.

LikeLike

Excellent article, Paul – great photos. I must check Elsie Dunn’s papers when next in SLQ. Regards, Bevyn Jarrott

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bevyn

LikeLike

Thanks Beyyn

LikeLike