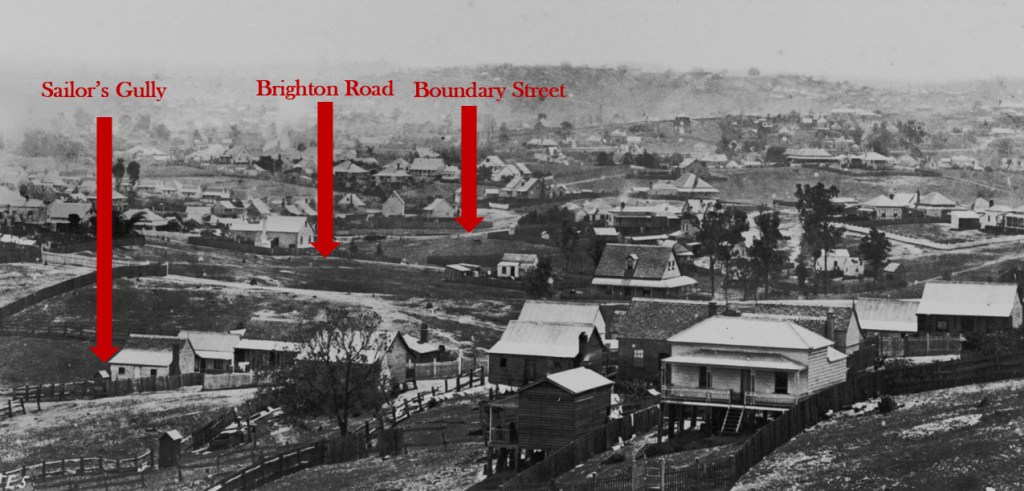

Walking down Hove Street in Brisbane’s Highgate Hill is like a trip into the past. There are many 19th century houses on the way down to the end of the street, where once springs fed babbling creeks lined with ferns. This is Sailors’ Gully.

There are intriguing references to this location over a 30 year period from the 1870s. A 1930s description mentions runaway sailors living in tents, and some later settling permanently with their families. My research has uncovered the stories of desertion from 3 ships, and of four sailors and their families who made their homes here.

The location

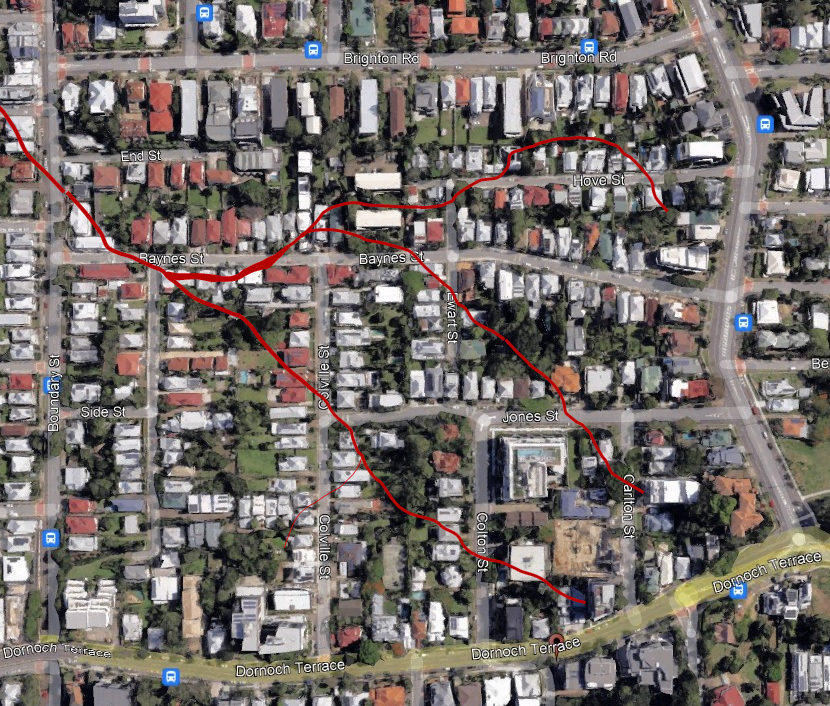

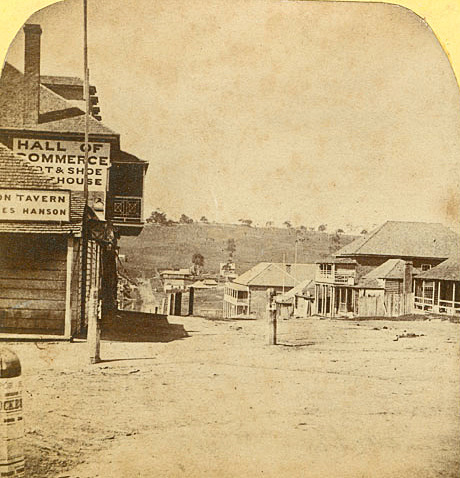

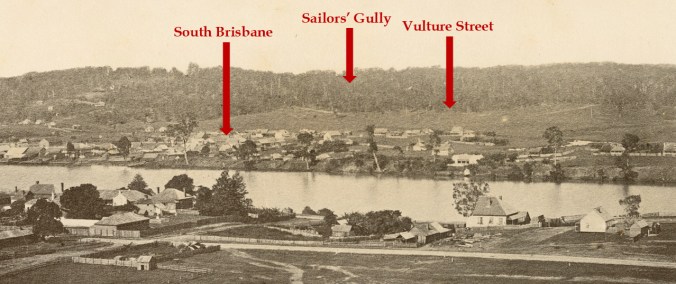

References to Sailors’ Gully start with the electoral roll of 1874, and end in 1899 in association with Council drainage work. The name Highgate Hill derives from an 1864 subdivision of land by Nehemiah Bartley under the name Highgate Hill Estate. Over time, Highgate Hill was used for a wider area encompassing Sailor’s Gully and eventually became the suburb name. Sailors’ Gully faded from memory.

The gully occupies a bowl between the ridges followed by Brighton and Hampstead Roads and Dornoch Terrace. It originally contained converging water courses, which were diverted into a drainage system completed in 1899.

A creek ran from the gully’s end at Boundary Street through West End and emptied into the Melbourne Street swamp. A newspaper article written in 1930 described this creek, and there’s further detail in my post Kurilpa, Water Water Everywhere.

The origin of the name

There are two versions of how Sailor’s Gully got its name.

A 1930 newspaper article on the history of Highgate Hill tells of runaway sailors.

“A tent community was formed in the gullies between Dornoch-terrace and Vulture Street. They were runaway sailors who had deserted ship, and lived in tents with their families Eventually, a number of them built homes, and in some cases their descendants are still living in the same locality, which, appropriately enough, had been called Sailors’ Gully.”

Another explanation was given in an anonymous letter to the editor that appeared in the Brisbane Courier in 1923. The author, who states that he was born in South Brisbane in 1862, explains simply that “it got that name because a few of the seamen of the riverboats bought ground, and settled there“.

Sailor desertion in the 1860s

Queensland became a separate colony in 1859. A major objective of the new government was to increase immigration. The instigation of assisted passages and a system of land orders that could be used to purchase land at government auctions quickly boosted arrivals.

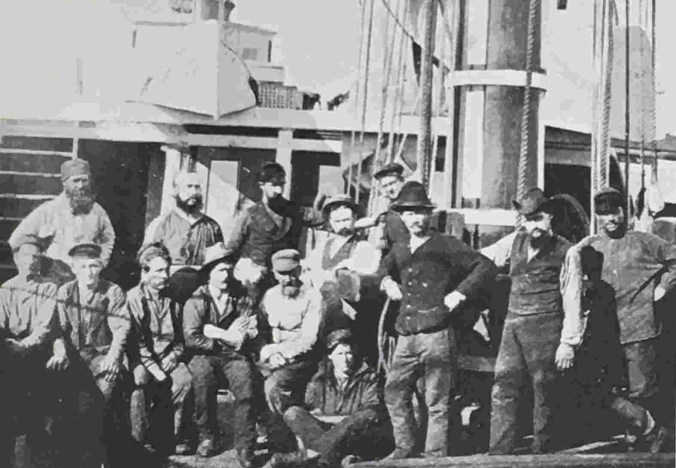

During 1862, 18 immigrant ships arrived in Moreton Bay and all lost some of their crew to desertion. For many sailors, the chance for a new life in Queensland proved irresistible. Some encountered problems with the officers on board, and others formed romantic attachments with female immigrants. The financial cost was high, as sailors were usually paid for the voyage after the ship arrived back at its home port.

The number of deserting sailors was so high that ships often left Brisbane with a greatly reduced crew. Some sailors managed to get away in a manner avoiding punishment. Others were tried for disobedience or desertion and were typically sentenced to 2 to 3 months with hard labour.

During 1862, 40% of the prisoners admitted to Brisbane Gaol were sailors. One newspaper report states that in December of 1862, there were 70 sailors in a jail with a nominal capacity of 108 male prisoners. That year, the Government purchased a ship which was to be anchored near the river mouth to serve as a prison for runaway sailors and relieve the crowding at Petrie Terrace.

A search for sailors

A breakthrough in identifying some of the Highgate Hill sailors came when I discovered that due to variations in use of the apostrophe, Sailors’ Gully appears as three separate references in transcriptions of Queensland electoral rolls from between 1874 and 1884. There are a total of 32 names listed.

After searching the Queensland State Archives indexes of crew names from the 1860s, I found three from the electoral roll. A fourth name came from a search of prison records. Here are their stories.

George Tidey and Charles White

Disobedience on the Persia

In November of 1861, the immigrant ship Persia completed its journey from Plymouth to Port Curtis, Gladstone. It was the first immigrant ship to arrive in Central Queensland.

The 100 day voyage had been eventful and tragic. A heavy gale washed away a lifeboat, there was a fire in the bakehouse, and the ship almost ran aground in heavy rain in the sub-Antarctic Crozet Islands.

There were 24 deaths including 17 children, 8 births, and one marriage during the voyage, with 430 immigrants arriving at Port Curtis. Passengers had been scandalised when “two libertine, girl-loving sailors managed one night to break into the young females’ department“.

When, at the request of the Captain, Gladstone police arrived on board to arrest the two sailors, a group of their shipmates crowded around protecting them, and refused orders to disperse. This was thought to be due to a disliked first mate and a desire to stay in Australia.

The Persia continued on from Port Curtis to Brisbane with 200 of the immigrants. There, fifteen of the Persia crew were sentenced to 12 weeks hard labour for disobedience to lawful commands at Port Curtis. Eight were discharged after a month at the Captain’s request and returned to the Persia, anchored at Brisbane Roads and ready to depart.

The Captain’s problems weren’t over, however, as four days later he contacted the Brisbane agents of his company, J & G Harris, via the Lytton telegraph office.

“I send this by Captain Jones. I cannot come on shore myself. Telegraph to Mr. Harris, and ask him to go to proper quarters for assistance to get my ship to sea. Send a good force of armed men, and engage a steamer to bring them at once. Beg of Mr. Brown to come with his men at once; it is very urgent.”

The Police Magistrate, together with twelve soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Seymour, and six of the town police under Inspector Griffin, headed out to Brisbane Roads in a river steamer and brought back 9 sailors, including 6 of those who had recently been released to rejoin the ship. They were sentenced to 12 weeks’ hard labour.

A few days later, the Persia sailed for Hong Kong with a cargo of 150 casks of bottled beer brought from England and 325 tons of coal.

The Tidey family

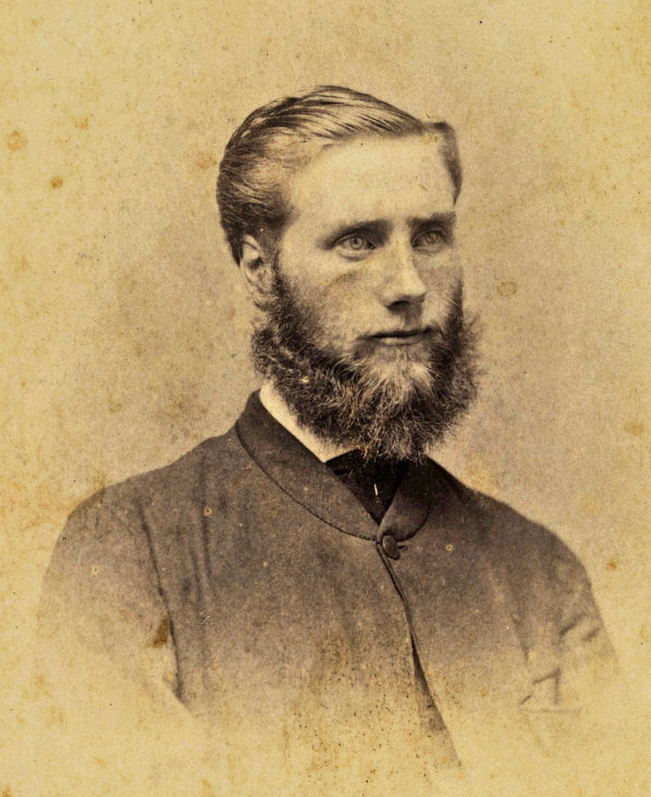

George Tidey (sometimes recorded as Tidy) was born in 1843 at Worthing, Broadwater, Sussex, England. He appears on the crew list of the Persia as an able seaman and was one of the sailors imprisoned for disobedience. Early in 1862, George was released from jail, and a year later, he married Bridget Moloney from Newmarket on Fergus, in County Clare, Ireland. The couple had 10 children, including one set of twins, and all sons except for a daughter in 1882.

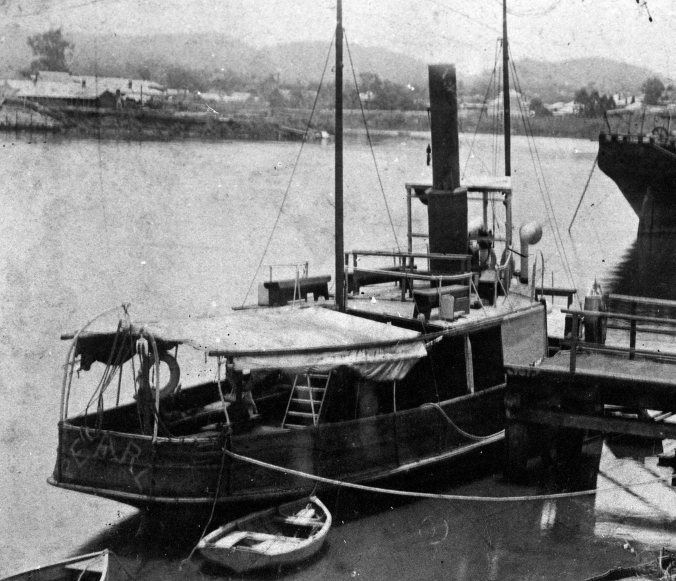

George was listed on the electoral roll at Sailors’ Gully and later Highgate Hill from 1874 until 1883. A descendant of George has entered information on him in FamilySearch, and there are also family recollections in MyHeritage. These stories are of George having jumped ship to stay in Australia and later working on river boats such as the Pearl and the Youngmat.

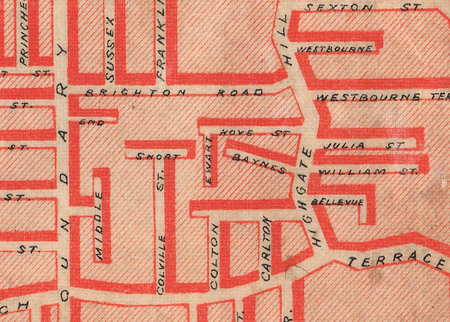

George owned land in the gully in Short Street, at what is today 45 Baynes Street, and this is likely to be the location of the family’s first home. He later purchased another block from Joseph Baynes on Hampstead Road near the corner of Baynes Street and sold the other property.

In 1877, George was still listed in the Post Office Directory as a seaman, but in 1882, he and Bridget started running hotels, initially at Indooroopilly.

Bridget died in 1887 when they were at the Brian Boru Hotel at Gatton, and the year after George married Harriet Elizabeth Gower. They had one son and continued running hotels in various locations. Harriet passed away in 1903 at just 44 years of age. George finished his hotel career as the publican at Eight Mile Plains in 1907.

In his final years, George lived in Annerley with the family of his son, John. In the 1913 electoral roll, despite over 20 years working as a publican, he gave his occupation as mariner. George died in 1917 aged 74.

The White family

Twenty-four year old Charles White was a shipmate of George Tidey on board the Persia and was in the same group jailed for twelve weeks in December, 1861. In July of 1862, five months after his release from prison, he married 18 year old Ellen Harvey.

Ellen had been a passenger on the Persia, so in Charles’ case, the motivation to desert was to start a new life with his shipboard sweetheart. The couple had eight children between 1863 and 1887, with five surviving to adulthood. Successive electoral rolls and post office directories from the 1870s show Charles and Ellen living in Baynes Street.

Charles was the only one of the sailors that I have identified who continued working as a seaman for the rest of his life. From the late 1870s he was employed by the Queensland Harbours and Rivers Department.

In 1889, Charles was second mate on the dredge Hydra which was based for an extended period on the Norman River in the Cape of Carpentaria. A few years earlier, gold had been discovered at Croydon, spurring the development of the area.

Towards the end of the year, a steam launch and coal punt became stuck in the sand, and Charles and three others were sent by Captain Sunners to try to get them off at high tide.

They became stranded in strong weather and went for 4 days with no food and little water before they could return to Karumba. Charles claimed that he had been verbally abused by Captain Sunners on his return and he resigned and returned to Brisbane.

After formally complaining, his version of events was rejected in favour of Captain Sunners’ statement that they could have easily returned. Charles was told that he would not be employed by the Department again. The issue was raised in parliament by Thomas Glassey and James Drake, but Minister Macrossan rejected the requests for an enquiry, siding with Captain Sunners.

Charles retorted in a letter to the editor in which he cited testimony by other crew members that they had offered to take food to Charles and his men, but Sunners had rejected the request, saying that they “could eat snakes and rats“.

At the time of his death in 1904, 67 year old Charles was still working, by then as a deckhand on the “Grazier“. This vessel was owned by the Baynes family’s Graziers Butchering Company and was used to transport meat.

While loading the ship at the Queensport meatworks,Charles fell into winch machinery and was badly injured. He died two days later and the company flew their flag at half mast for a day in respect. Ellen continued to live in Baynes Street until she passed away 2 years later.

Robert O’Brien

Desertion from the Conway

The Conway was built in St John, Canada in 1851. After a few years operating as a general cargo ship, in 1853 she started transporting immigrants to Australia. By 1862, she was engaged in the Queensland subsidised immigration scheme.

Having departed Southampton in August, the Conway arrived in Moreton Bay 102 days later with 396 immigrants onboard. Of these, 96 were single women selected by Maria Rye, who had founded the Female Middle Class Emigration Society the year before.

At that time, ships usually anchored at Brisbane Roads, near the mouth of the river. In the days before major dredging, this avoided the time consuming journey up the river with its shifting sandbanks.

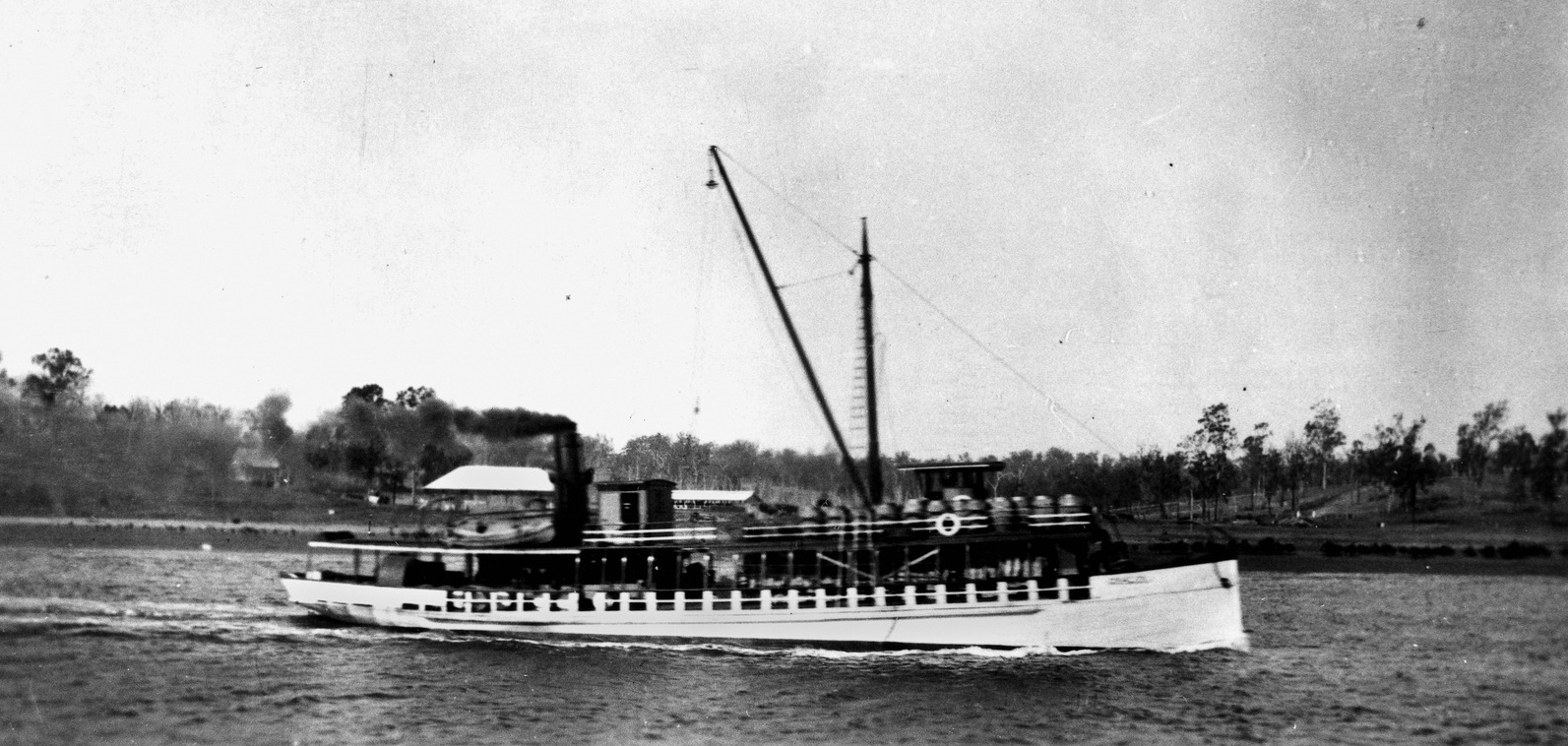

Immigrants completed their journey on one of the many Brisbane paddle steamers.

A few days after their arrival, a group of the Conway passengers were on their way up river on the steamer Rainbow. When passing by Breakfast Creek, a group of 10 sailors who had hidden amongst the immigrants appeared on deck, jumped into the river, and swam ashore. The badly decomposed body of one of them was later found floating in the river near Eagle Farm.

Five others hiding on the Rainbow who had balked at swimming ashore were discovered and duly tried for desertion. It transpired that Captain Spence had promised to discharge them on arrival but had later changed his mind. As a result, they were given a light one month sentence. The 15 sailors who had hidden on the Rainbow represented almost half of the Conway‘s crew of 40.

A few days later, three of the runaway sailors ran into one of the ship’s male passengers, Francis Davis, at the Sovereign Hotel in Little Ipswich. They accused him of informing the Captain of their plan to abscond, and a fight broke out. One of the sailors, a Swede named Christian Anderson, pulled out an 8 inch (20 centimetre) double-edged knife and threatened to give Davis “3 inches of cold steel”.

When two policemen arrived, Anderson ran for the door, exclaiming, “By the Holy Jesus no man shall take me”. After a struggle, the police wrestled him to the ground. The three runaways were sentenced and fined. Unable to pay the fine, their sentence was extended and they were finally released in October, 10 months later.

The O’Brien family

One of those who successfully swam from the Rainbow to the riverbank at Breakfast Creek was Robert Valentine O’Brien. He was born in Dublin, Ireland, in 1842. Robert had a strong motivation to run away, as he had met his future wife on board. Eighteen year old Ellen Prest1 was from Poplar in Middlesex, a village that by then had been swallowed up by an expanding London.

Robert avoided being arrested, and the two married five months later. Two others of the runaway sailors also married women who had been passengers on the Conway.

Robert initially found local employment as a sailor. He appears in the 1874 electoral roll living in Sailors’ Gully, and the 1878 post office directory lists him as a labourer. By 1886, the O’Briens were living at 3 Colville Street. The current house on the lot appears to be of later construction.

From the 1880s, Robert worked as a carpenter, and in the 1890s Ellen ran Colville Store, possibly from their home also named Colville.

Robert passed away in 1898 and Ellen continued living in Colville Street. From around 1908, Ellen, a member of the Trained Nurses Association, ran a midwifery practice from there. Her obituary states that she had been a nurse since the late 1880s. Regular birth notices mentioning Nurse O’Brien were published from 1908 until 1915, when her health started to deteriorate and she probably ceased practising.

The couple had five sons, six daughters, 28 grandchildren, and at the time of Ellen’s death in 1919, four great grandchildren. Their last child, Colville Edward “Jack” O’Brien, served in the 26th Battalion of the 1st AIF. He lost his life on the first day of the Allied offensive in August 1918 that was to end the war.

The family had become quite prosperous, as can be seen from their plot in South Brisbane Cemetery which includes a memorial to Jack.

John Stride

Insurrection on the City of Brisbane

The City of Brisbane dropped anchor in Moreton Bay in June of 1862 with a crew of 39, of which 21 were seamen. The rest were officers, the purser, stewards, cooks, and a storekeeper. Most of the seamen deserted. A newspaper reported that “at her mizen the police flag has been flying over her since arrival“. This was a means of alerting the Water Police to the need for their assistance with problems onboard.

With a constant flow of sailors deserting, the Water Police were reorganising to manage the situation. A detachment was camping at Luggage Point while the hulk Julia Percy was being prepared to serve as a police station and prison. Brisbane Gaol was badly overcrowded. During 1862, of the 590 admissions, 229 or around 40%, were sailors.

Shortly after the ship’s arrival, one seaman was found hiding on the steamer Hawk and given a 12 week sentence. A few weeks later, 8 others were jailed for a month for disobeying orders. They asserted that the first mate had used threatening language, and while the intention was to return them to the City of Brisbane before she sailed, they vowed never to return.

As the date of the departure on the City of Brisbane drew close, she was left with almost no crew due to desertion, and several seamen were engaged in Sydney and travelled up on the steamer Telegraph. However, on arrival, they refused to board the ship.

The nine jailed sailors were brought back, but there was a general insurrection of the crew. All 15 remaining seamen were placed in irons by the police, and the ship was taken to sea with the temporary assistance of sailors from the Theres, and then departed for Peru manned by the officers, cook, steward and carpenter, with the sailors locked up below decks.

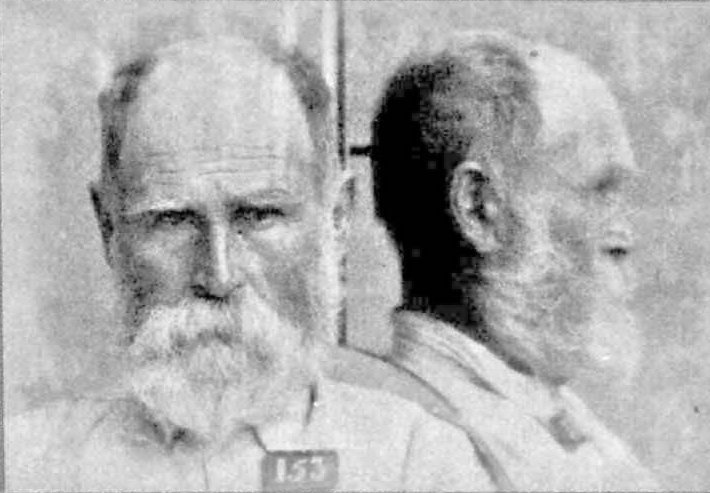

The Stride family

John Stride appears in the 1874 electoral role at Sailor’s Gully. In an 1890s prison record, his arrival in Brisbane is noted as being on the City of Brisbane in 1861. John does not appear on the crew list, but is listed as a crew member of the Morning Star, which arrived in Sydney in June of 1861. He is probably one of the sailors brought up from Sydney who refused to board the City of Brisbane.

John was born in Evercreech, Somerset, in 1834 and he had spent time in the Royal Navy. In 1865, he married Jane Chisholm and they had two daughters and three sons, one of whom died in infancy.

The family lived in Hove Street, Sailors’ Gully, from at least the early 1870s, except for a period around 1875, when they were at the Enoggera Waterworks. John was employed by the Board of Waterworks from the early 1870s as a pipe layer. Jane passed away in 1880, and by 1891, John had fallen on hard times.

At the time vagrancy, or homelessness, was a crime. In the 1890s, John served a total of 8 sentences for vagrancy, amounting to 22 months in Boggo Road Gaol. He also served shorter sentences for theft, including that of a tomahawk from a Fire Station, a purse and cloth, and a frying pan worth one shilling and ninepence.

John died in 1892 from heart failure.

Mary Whitta nee Stride

In 1889, John and Jane’s second child, Mary, married Thomas Whitta. In the 1890s and 1900s, Thomas worked at various places in the Rockhampton area including the Keppel Bay Pilot Station and the Hector Gold Mine.

By 1907, Mary was back at Hove Street with her children, and Thomas was admitted to the Goodna Asylum where he died the following year. Mary worked as a charwoman, or cleaner, until the older children were able to support her. She was to live at Hove Street until her death in 1960 at age 92.

Conclusion

At least four runaway sailors made their homes in Sailors’ Gully.

Whilst I have found no contemporary references, the story of Sailors’ Gully starting as a tent community of runaway sailors is quite plausible. It’s likely that groups of seamen who had been shipmates, planned their desertion, and in some cases served prison terms together, would also initially stick together.

In the 1860s, it was not unusual for immigrants to live in tents for a period after arriving in Brisbane. There are mentions of groups camping not far from Sailors’ Gully in today’s Musgrave Park, Jane Street in West End and on Highgate Hill.

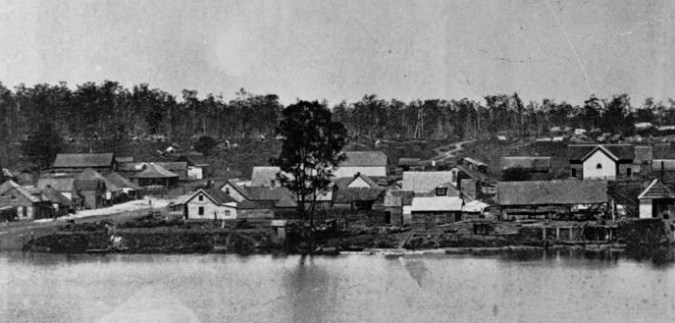

Sailors’ Gully was discreetly located beyond the treeline that followed Vulture Street, and was only a 20 minute walk from South Brisbane. It also had a reliable water supply. An 1878 advertisement for a house, today located at 49 Baynes Street, mentions ” a spring of pure water, which has supplied the whole neighbourhood during the late drought”.

Sailors’ Gully today

Appendix – Sailors’ Gully in later years

By the 1880s, most of the rough dirt tracks heading down into the gully had been named.

By 1906, Baynes Street had been extended from how it appears in the map above to encompass Short Street and reach Boundary Street. Stevens Street, unnamed on the map above, was linked to Colville Street a few years later.

Stevens Street, named after the first European owner Samuel Stevens, was the home of the Welsh Jones family for many years. William Jones served as an alderman in the South Brisbane City Council for 12 years and was mayor in 1893 and 1904. After his death in 1916, the street was renamed in his honour.

The boot factory

With the value of boots and shoes imported into Queensland in 1880 sitting at around 179,000, there was great incentive for establishing local manufacturing, and numerous small boot factories sprang up around Brisbane.

One of these, initially called the Stanley Boot and Shoe Factory, was established in around 1888 in Sailors’ Gully, adjacent to the O’Brien’s home on Colville Street. It was owned or run by Joseph Laurence. Availability of water from the creek may have been a factor in its location.

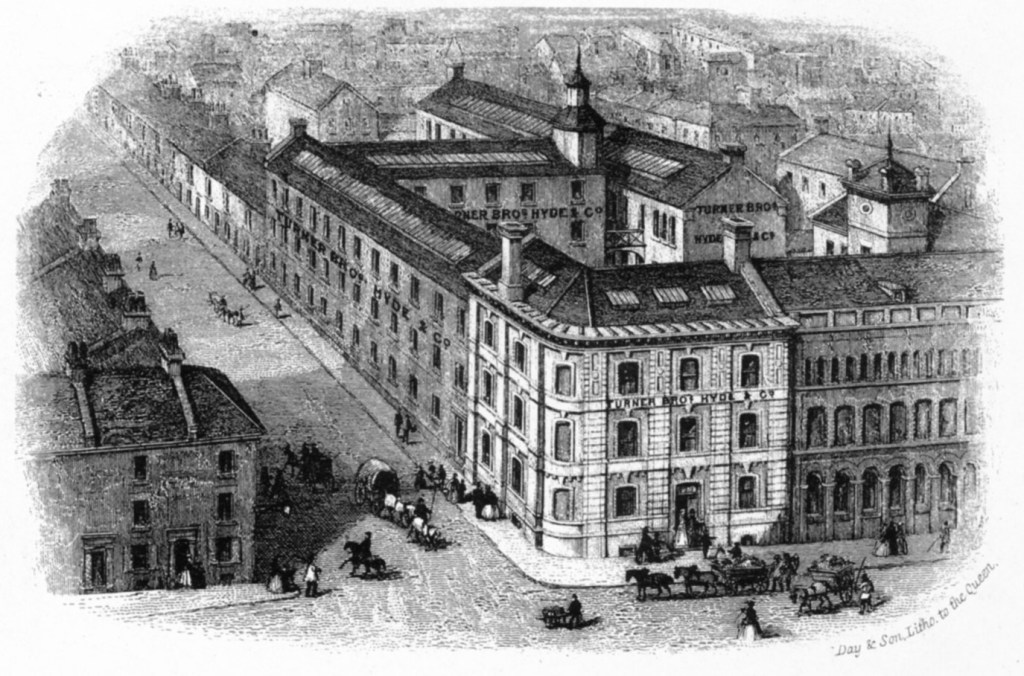

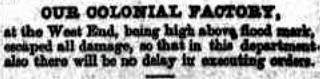

Boot making was a labour intensive process, and an advertisement for employees in 1890 sought “twenty to thirty makers and finishers of all classes of work”. By the time of the flood in 1893, the factory was producing boots under the name of a large English firm, Turner Brothers Hyde and Company.

The company’s stock in Elizabeth Street was badly damaged by the 1893 flood, but it was able to fall back on the boots produced at the Colville Street factory. At this point in time, H. T. Field is mentioned as the “Attorney’ for the company, in the sense of a person who has the legal right to act for someone else.

The details of Field’s relationship with Turner Brothers & Co. are not clear, but in 1895, H. T. Field and Co. as occupiers were advertising the factory to let. This year saw a boot makers strike that lasted 14 weeks from May until August and the factory was not leased out.

Just 3 months later the firm was declared insolvent and no more is heard of it. The factory buildings were still in situ circa 1889 when plans were prepared for the drainage of Sailors’ Gully.

The creeks disappear

In 1892, the South Brisbane City Council started discussing the building of a drainage system in Sailors’ Gully, but work didn’t commence until 1899.

Despite the drainage system, some buildings along the old creek lines still occasionally experience flooding after heavy rain.

Sailors’ Gully retains many homes with gable or steep pyramid roofs, typical of the 1870s.

References and notes

- Ellen Prest does not appear in the passenger list for the Conway held by Queensland State Archives, but is listed in National Archives of Australia Series J715 “Ships passengers lists – Brisbane – inwards – chronological series” which has been indexed by the Queensland Family History Society.

© P. Granville 2025

So good Paul, thank you for all your research on our little neck of the woods/gully.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks It’s nice to get some feedback!

LikeLike

Paul, an excellent piece of work.

Now I have to walk over to see it.

Bill

Dr William J Metcalf

Adjunct Lecturer, Griffith University,

Honorary Associate Professor, University of Queensland,

Brisbane, Australia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely fascinating. My gre

LikeLike

Hi Catherine

Unfortunately your message has been truncated. I’d love to get the full message from you . One option is to use the ‘ contact me’ feature to send an email . Paul

LikeLike

Extraordinary attention to detail to provide such a well rounded article of local history. I have enjoyed each and every read created by Paul, this one being particularly close to home. So very appreciative of your time and efforts to make the past of our local streets so easily accessible by bringing them back to life.

LikeLike

Thanks so much Tracie for your very kind comment.

LikeLike