In 1875, the Anglican parishioners of South Brisbane devised a plan to obtain the perfect block of land on which to erect their new church of St. Andrew’s. The plan was disrupted by a neighbour, and parishioners had to build their new church on a much shorter and lower part of the block. Thirteen years later, they finally acquired the missing land, and then only through an unusual sequence of events.

The first Anglican church in South Brisbane

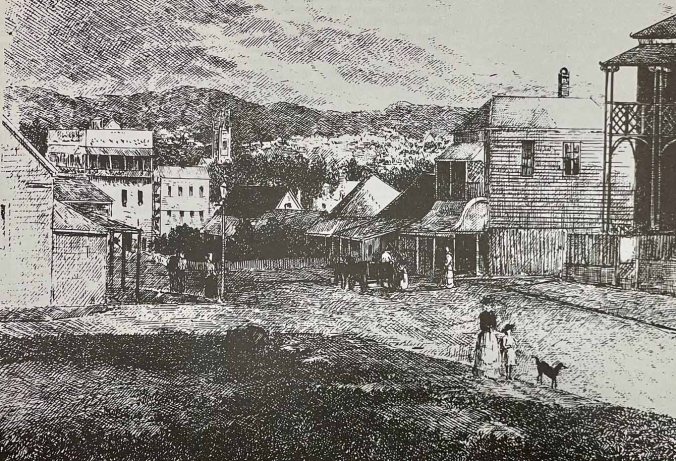

In 1842, Moreton Bay was declared open to free European settlement and squatters’ men began arriving regularly at South Brisbane with bullock teams hauling bales of wool. The small South Brisbane settlement slowly grew, with the development of shipping, light industry and surrounding farms.

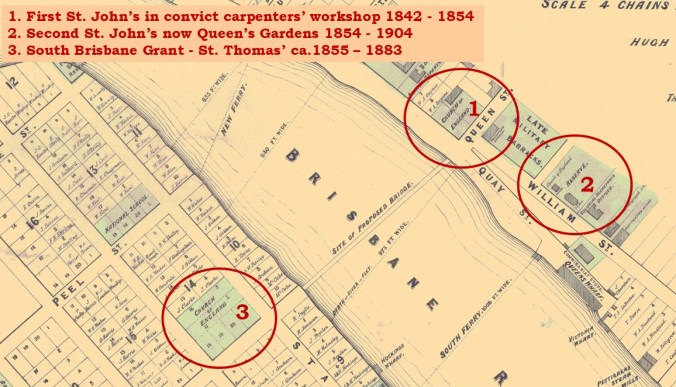

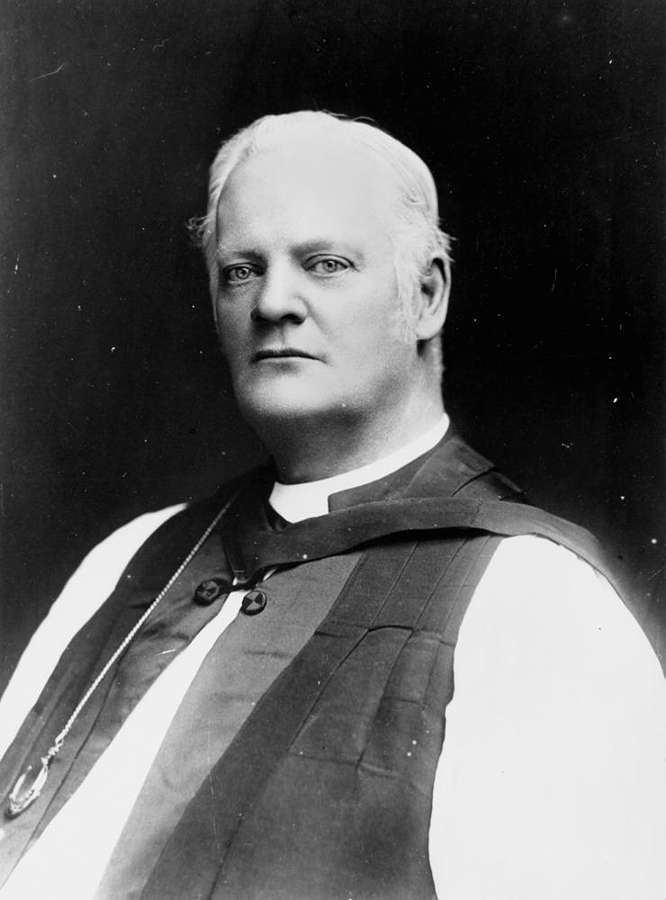

In 1849, at the instigation of Bishop William Tyrell, the NSW government granted land for a South Brisbane Anglican church, school and parsonage at the location today of the Queensland Museum and Art Gallery.

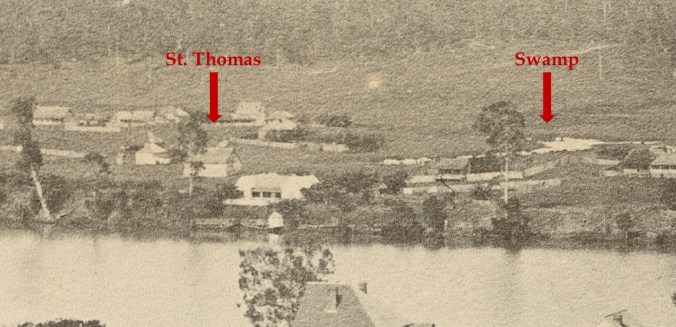

By the mid 1850s, a small church had been built on the site and given the name St. Thomas’. It was unfortunately located on low lying land close to an extensive swamp which stretched down both Melbourne and Merivale Streets.

In a newspaper report from 1905, long term parishioners Miss Thompson and Miss Green recalled the church being used during the week as a schoolroom and as a place for lantern entertainment. There was no fence around the property in the old days,

“the consequence being that animals strayed around freely. On one occasion a cow was surprised in the vestry, and on another some goats were discovered under the communion table.”

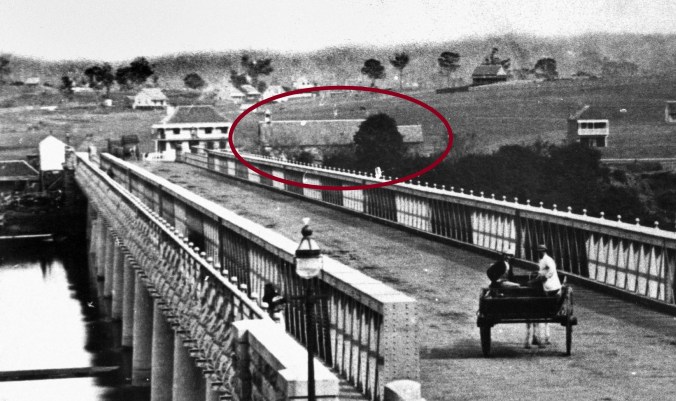

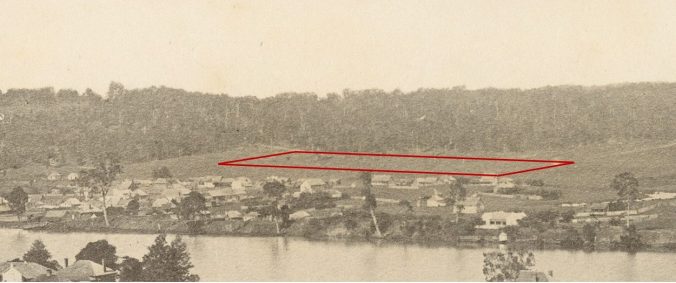

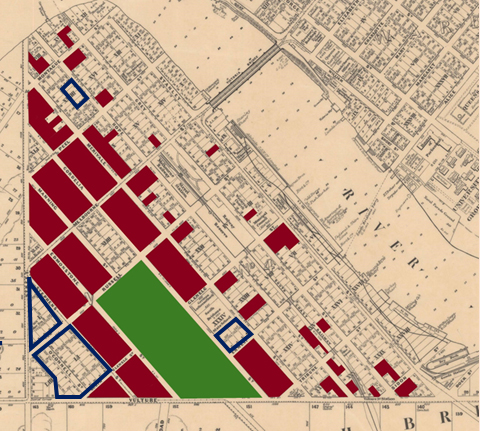

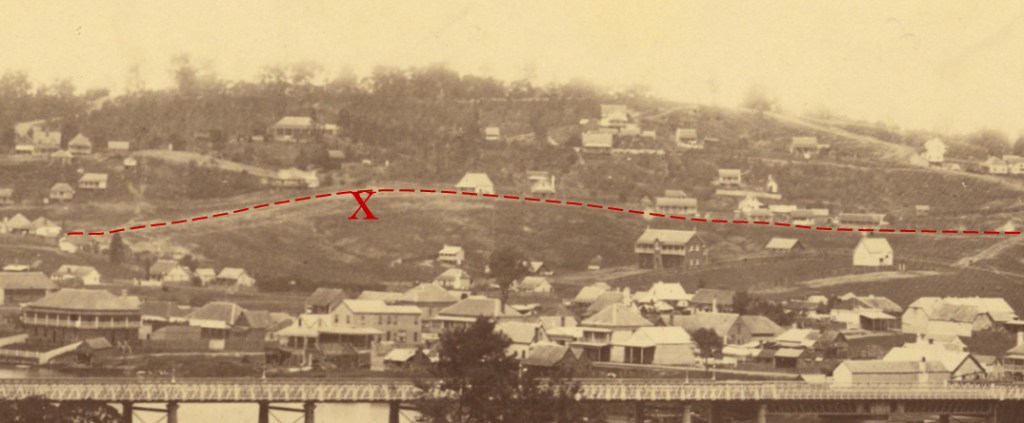

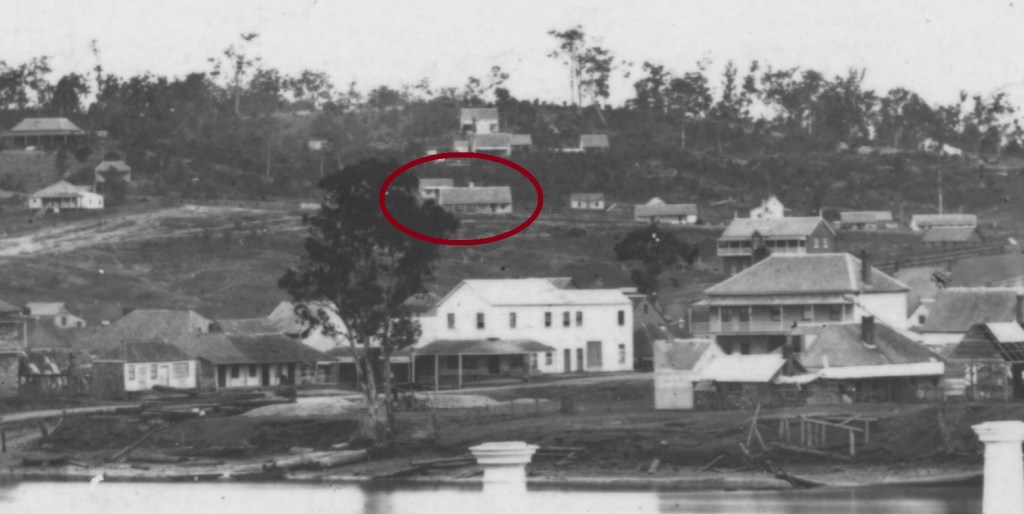

As I described in a previous post, after ten years of political intrigue, mismanagement, and financial crisis, the Victoria Bridge finally opened in 1874. The image below from around that time shows a now enlarged St. Thomas’ church at a significantly lower level than the bridge.

By this time, parishioners would have seen water coming perilously close to or entering the church in the floods of 1857, 1864 and 1870, all of which exceeded 3 metres. They wanted a larger and more imposing church, but on higher land.

Looking for land

There was little opportunity to purchase suitable land for the new church. A recreation reserve, given the name Musgrave Park in 1883, occupied a large area ( see my post Musgrave Park – The Early Days). In 1865, five trustees had been appointed to maintain and manage the reserve in the public’s interest.

Also, in 1864 the Colonial Government had transferred to the Corporation of Brisbane almost all of the land in South Brisbane that had not yet been sold. With most country members of parliament unwilling to fund a Brisbane bridge, this was a political compromise to allow work to proceed.

Commonly known as the Bridge Lands, this also included large parts of what is today Dutton Park. The Council mortgaged most of it to the Bank of Queensland to pay for the construction work. For more on this, see my post The Fascinating Story of the First Victoria Bridge.

The 1874 land sale

In September 1874, with the bridge completed, the government decided that the time was ripe to sell the small number of remaining blocks in South Brisbane that were not part of the Bridge Lands. The bidding was spirited, and 36 perch (910 square metre) blocks sold for between £22 and £32.

After the sale, all of the vacant land north of Vulture Street was either part of the recreation reserve, mortgaged Bridge Land, or town blocks of around 900 square metres with private owners. Further south, beyond Vulture Street, only limited subdivision had occurred. Most blocks were of 6 acres (2,400 square metres) or more, too large for the church and distant from the community. The building committee needed an innovative approach.

Influence at work

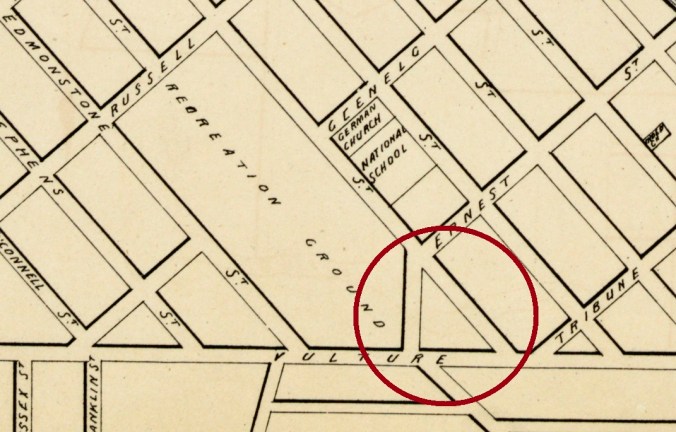

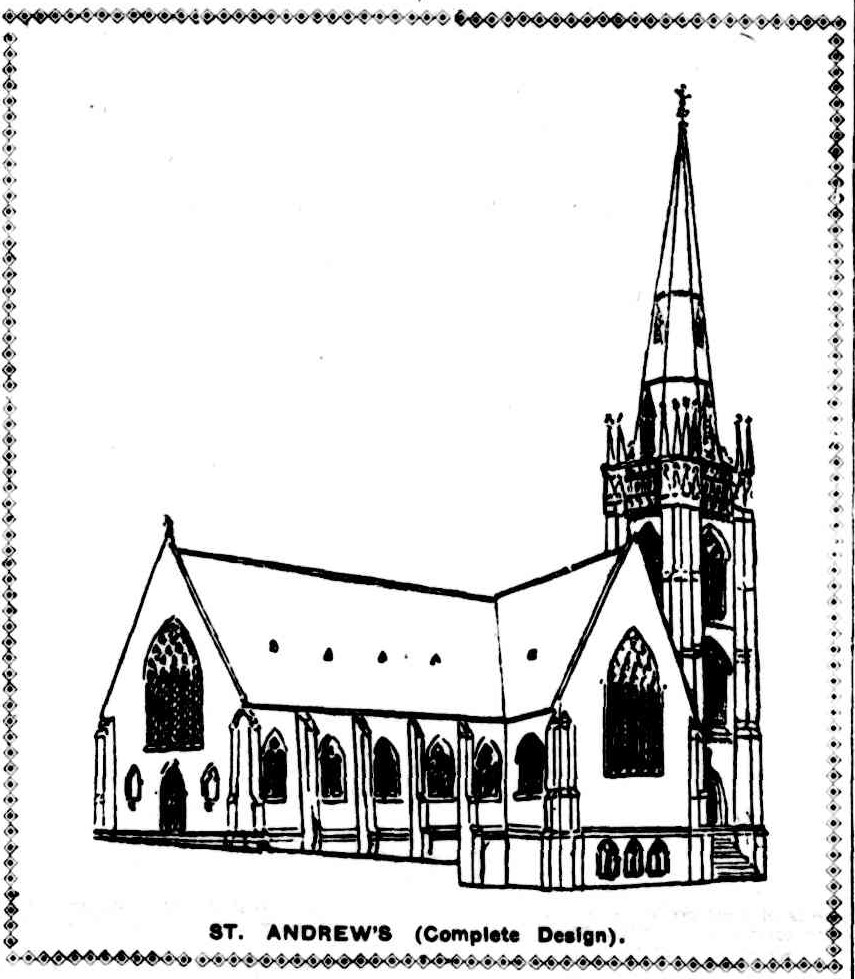

The Anglican parish building committee identified the south-east corner of the recreation reserve as an ideal location for their new church. Its flood free location on a high point of Vulture Street would make the church visible from much of Brisbane. However, acquisition would require them to convince those responsible to agree to excise a section from the recreation reserve, and then sell it at a public auction.

There was no shortage of influential parishioners who could have assisted in achieving this. In 1878, the building committee was reported to include William Theophilus Blakeney, the Queensland Registrar-General and a trustee of the recreation reserve, Edward Deighton, Under Secretary of Works and John Gerard Anderson, in 1875 General Inspector of Schools and from 1878 Under Secretary of Public Instruction. Under-secretaries were public servants in charge of departments.

The secretary of the building committee was retired Indian Army Colonel E. R. D. Ross, who was active as a magistrate and well known through his extensive charitable activities.

As well as Blakeney, two other of the five trustees of the recreation reserve, William Baynes and committee member Albert Hockings, were parishioners.

Their efforts were successful and the south-east corner of the recreation reserve was excised.

The parish bidders

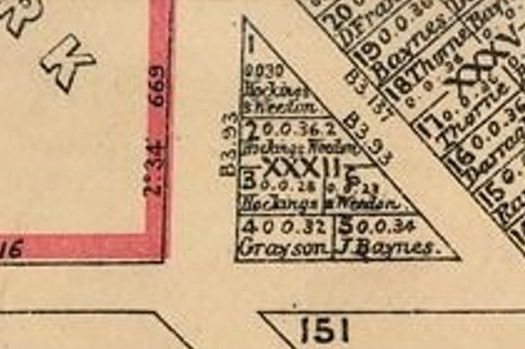

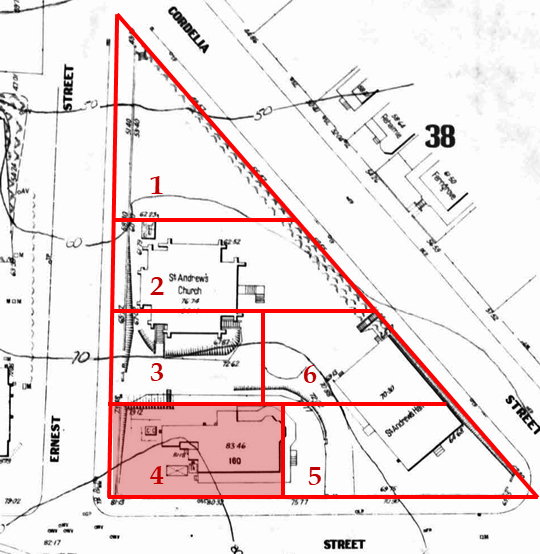

The excised land was split into 6 allotments, each of around 32 perches (800 square metres) and put up for sale by the Queensland government. At the auction, most were purchased by two representatives of the parish, Albert Hockings and Thomas Weedon. A 1905 newspaper article gives an explanation of the financial plan.

“Funds for the purchase of the land were lent by a small syndicate of parishioners, who contributed the necessary amount between them, and under a deed of agreement, drawn up by Mr. P. Macpherson, (now the Hon. P. Macpherson, M.L.C.), the money was eventually repaid to them without interest.”

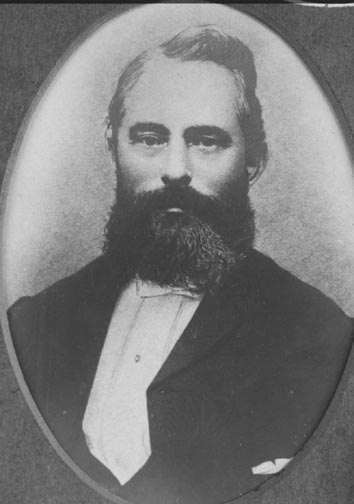

Albert Hockings

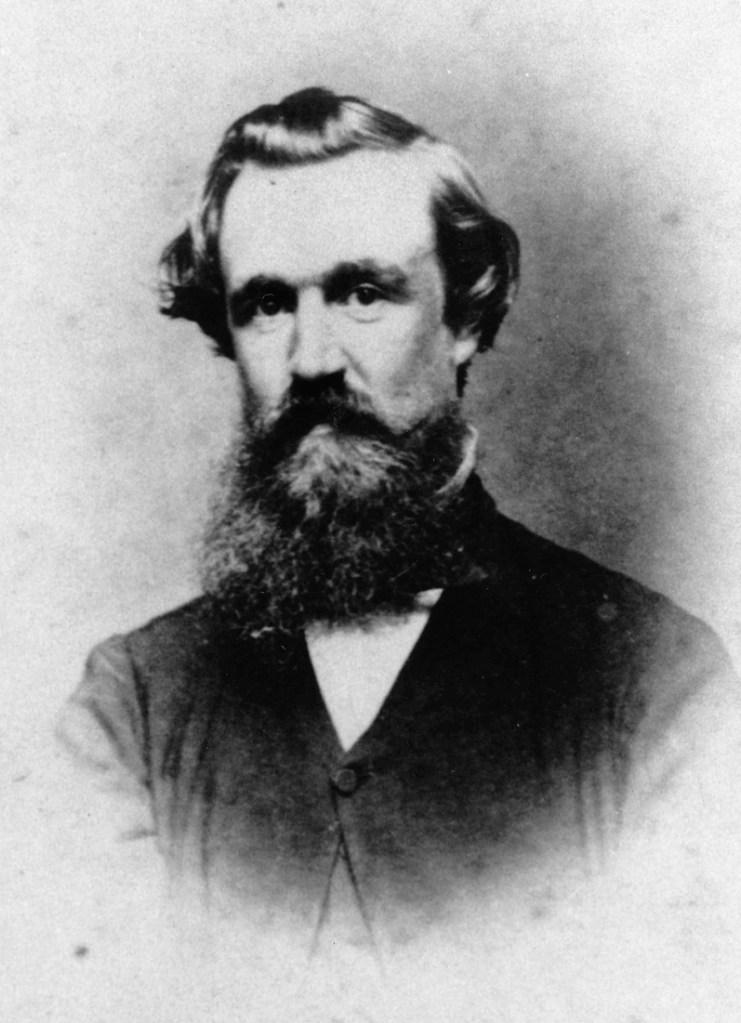

In 1846, Albert Hockings moved to Brisbane from Sydney where he had arrived as a teenager in 1841. He ran various enterprises, but became best known for his Rosaville Nursery at South Brisbane, where he spent decades acclimatising and breeding plants suitable for Queensland’s climate.

Hockings was also very active in community affairs. He was an alderman for many years and Mayor of Brisbane in 1865 and 1867. Hockings served as President of the South Brisbane Mechanics’ Institute, was a trustee for the South Brisbane Recreation Reserve and the South Brisbane Cemetery, and was a member of the Board of General Education.

For a fuller description of his life, see my post “Albert Hockings and his Rosaville Nursery“

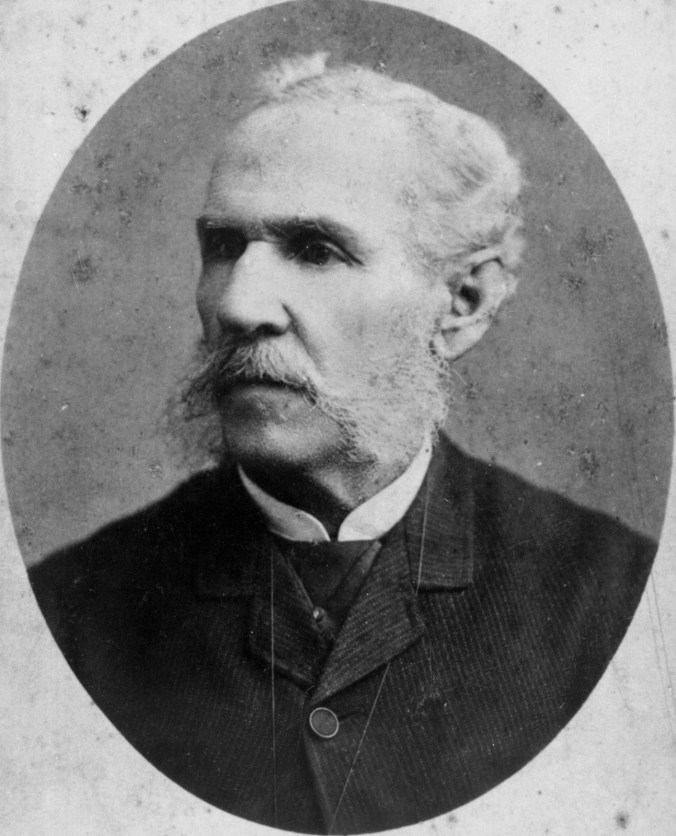

Thomas Weedon

Thomas Weedon first arrived in Brisbane in 1863. After a few years in Sydney where he managed a paper mill, he and his second wife Phyliss returned to Brisbane and made their home at a house they called The Wilderness on Hawthorne Street, Woolloongabba.

Thomas and Phyllis had been active parishioners at St Thomas, and later supported the establishment of Holy Trinity church across Hawthorne Street from their home. Thomas was a lay reader there for many years. Phyllis was a co-founder of the Brisbane Hospital for Sick Children. She bequeathed her entire estate to Holy Trinity Church.

Joseph Baynes

Joseph Baynes was the third and probably unplanned bidder for the parish. He had a watch and clock-making business in the city and lived on Vulture Street. His brother William, who was on the church building committee, ran the well-known Graziers Butchering Company.

The auction

The auction of the land took place on the 26th of October, 1875. The reserve price was £100 per acre, or £20 for a 32 perch block. At the land sale in the previous year, the highest prices were the equivalent of £31 for a 32 perch block.

The auction moved through each of the allotments from north to south. Only a summary of the auction results was published, without any commentary on the bidding.

The first four allotments were purchased by Hockings and Weeden, according to plan. Lot 1, an awkwardly shaped triangular block of 30 perches, sold for £34.

Whilst allotment 2 sold for a similar price to the first, 3 and 6 went for £55 and £61 respectively. These amounts were around double those of the previous year’s auction. They were also well over the reserve price, an indication that bidding was lively.

Things went awry when David Grayson outbid the parish representatives and purchased the prime block on Vulture Street, allotment 4, for £130. At this point, Joseph Baynes stepped in and secured the last allotment, number 5, for £135, avoiding a total disaster. However, without allotment 4, the church couldn’t be built on the highest part of the block as had been planned.

Who was this David Grayson who had frustrated the parishioners’ plans?

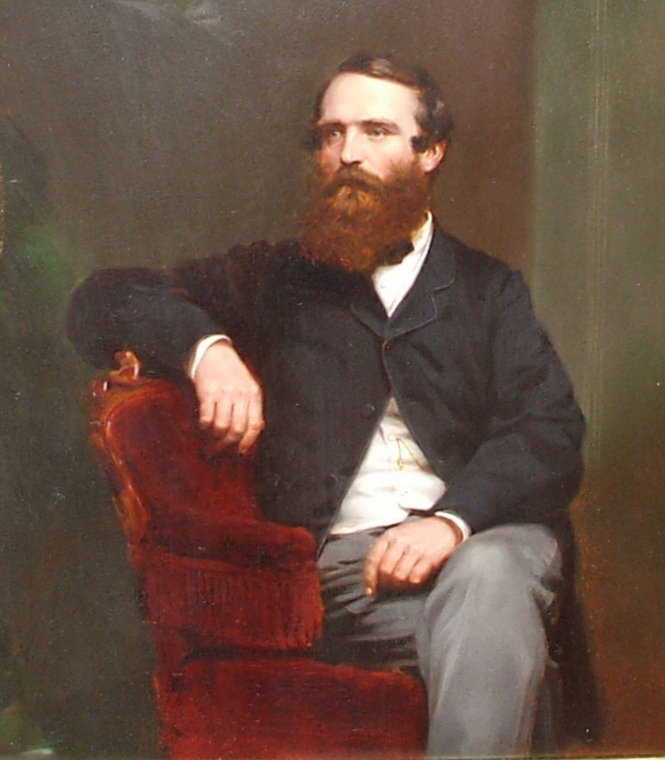

David Grayson – the “bumptious ex-alderman”

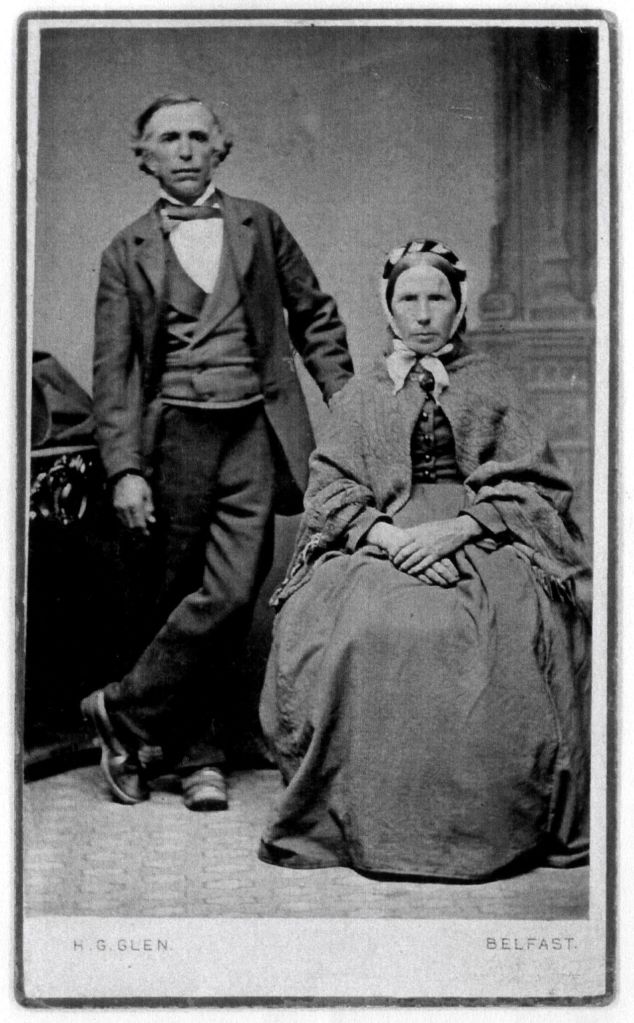

David Grayson was born in 1833 in the Parish of Seago, County Armagh, Northern Ireland. He emigrated to Australia in 1855 and in 1859 married Elizabeth McKee. She was also from Northern Ireland. In around 1860 the family, by then including a baby daughter Jane, moved from Sydney to Brisbane.

Grayson worked as a storeman for E. B. Forrest, who moved from Sydney to Brisbane in 1860 to establish a Brisbane branch of the Colonial Sugar Refining Company. By the mid 1860s, the company was located at the Australian Steam Navigation Wharf on Eagle Street.

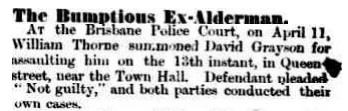

Grayson gained some notoriety over the years through his court appearances, usually after summoning someone who had assaulted him. Whilst he was usually successful, it begs the question of what provoked these assaults, and letters to the editor regarding Grayson are quite venomous.

In 1866, John Cameron wrote a letter accusing Grayson, accompanied by his toothless bulldog, of being a disruptive influence at the wharf, mentioning his ‘cadaverous countenance“. Another letter to the editor described an outburst by Grayson at a public meeting held by the local member T. B. Stephens as a “stupid and vapid peroration” and went on the describe him as “E. B. Forrest’s Mr. Lickspittle“.

Newspaper reports continued over the years. In 1872, for example, readers were treated to a description of an altercation on a rainy day between Grayson and a John Kennedy near the Alice Street ferry terminal, using their open umbrellas as weapons. Grayson claimed that Kennedy had “used towards him an opprobrious epithet“. The case was dismissed.

In 1871, the family home and an adjacent house Grayson owned on Vulture Street, opposite the site where St. Andrew’s would be built, both burnt to the ground. Despite this setback, his wealth steadily increased.

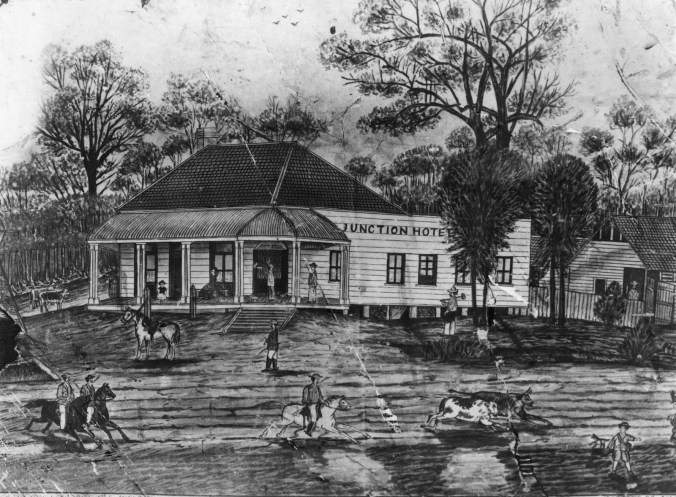

He was active in lending money for short term mortgages, a common approach at the time. The loans typically earned 12% interest. Grayson continually purchased property around Brisbane, including a farm at Brown’s Plains and the Junction Hotel at Annerley.

In 1872, Grayson was elected as alderman for South Brisbane, and three years later he had become chairman of the finance committee, responsible for approving purchases.

That year, in a court room crowded with spectators, he was tried for breaking the Municipality Act by approving the purchase by the Council of timber from himself. Despite barrister Isidore Blake’s interesting defence that Grayson’s election was irregular and therefore he wasn’t legally an alderman, he was found guilty .

Newspapers reported that Grayson, who had an annual income of over £4,000, refused to pay the £75 fine. He was taken to Brisbane Gaol in May of 1875 and served a 3 month sentence in lieu of paying the fine.

Later in 1875, Grayson was tried for assaulting William Thorne, whom he blamed for his conviction, calling him a “dirty informer”. Thorne, later mayor of Brisbane, had been the nominal complainant in the timber case. Grayson was found guilty and fined 40 shillings.

Grayson died in March 1877 at age 43, after what was reported as a long illness. The cause of death was “inflammation of brain” or encephalitis. This could have caused confusion and personality changes.

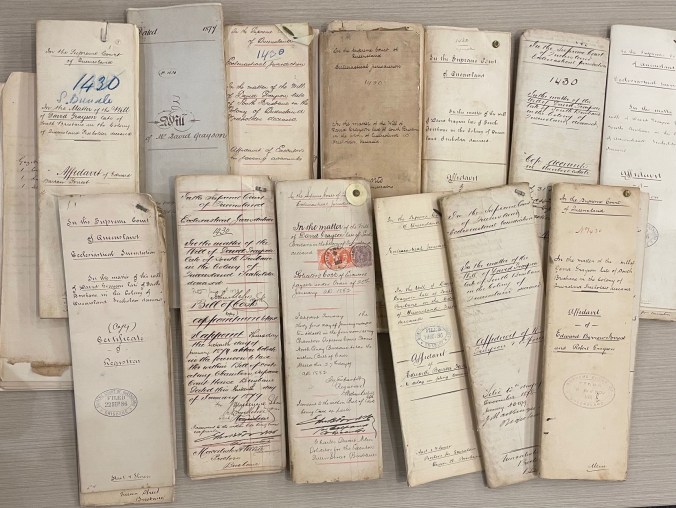

Grayson’s trust fund

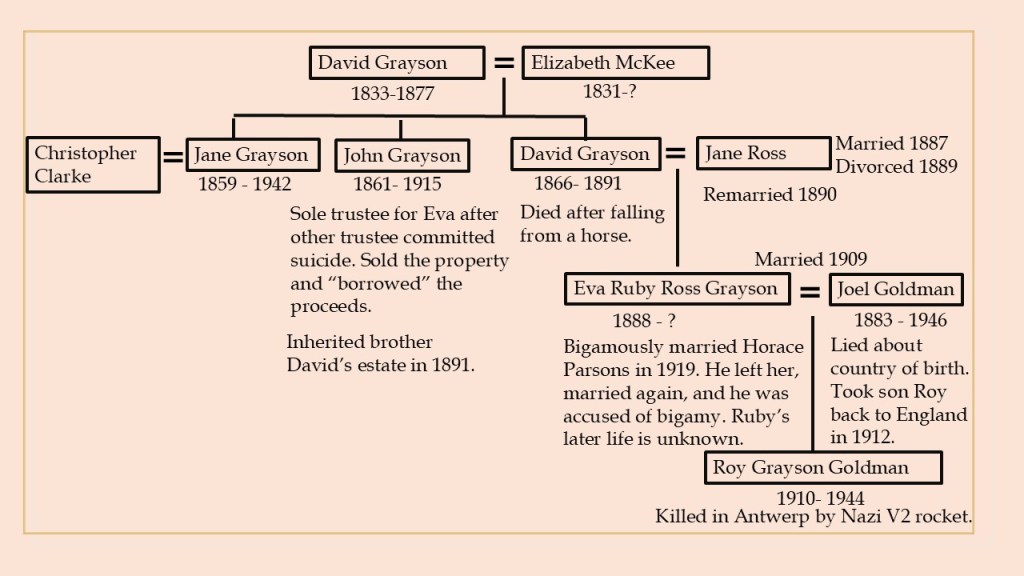

Grayson’s will specified that most of his large estate would be placed into a trust fund. It was to pay an income to his widow and support the education and maintenance of his 3 children. There were to be distributions to his daughter when she married or turned 21, and to his two sons when the youngest, David, reached 21 years of age in June, 1887. As the trust had significant income, none of the many property holdings were sold by the trustees.

The executors and trustees were Grayson’s old employer, Edward Barret Forrest, and his cousin, Robert Grayson, a country-based police sub-inspector.

Being based in the country, Robert Grayson played a minor part in managing the trust. On a misty night in 1888, he drowned in the Condamine River at Warwick on the way home from the pub.

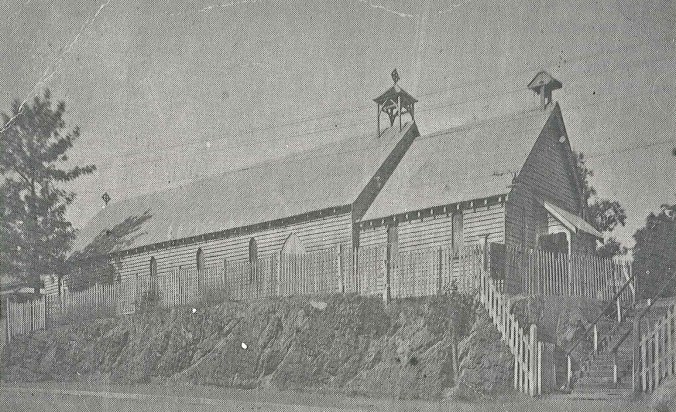

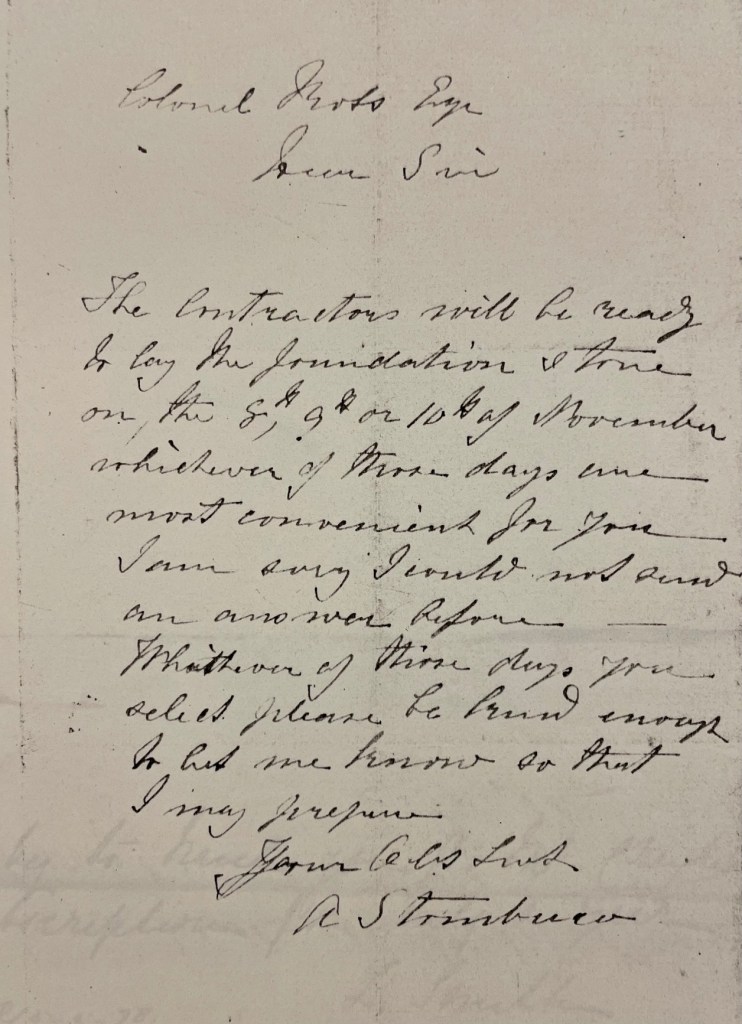

The church is built

By 1878, sufficient funds were available to commence construction of the church. Before his death, Grayson had refused requests to sell allotment 4 to the parish. In August, Samuel Grimley, on behalf of the building committee, wrote to trustee E.B. Forrest in one last attempt, requesting a lease on the land with the right to purchase in the future.

Forrest replied, stating that he did not think selling the property was in the trust’s best interests. He did offer to lease the block, with the right of first offer for the land when it eventually went on the market, but this was too risky an option for the parishioners.

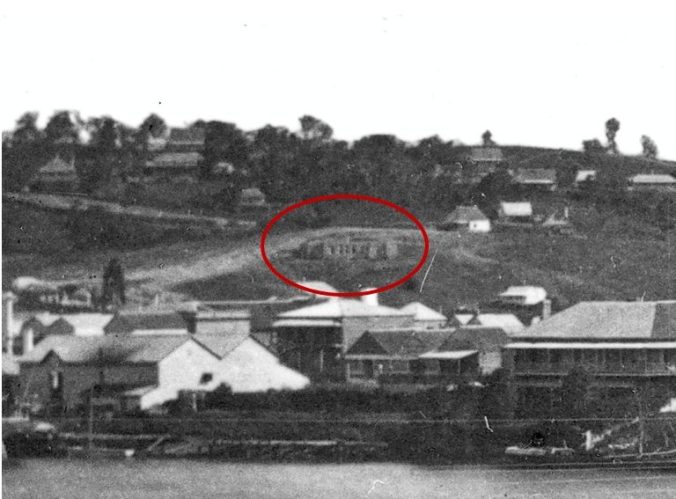

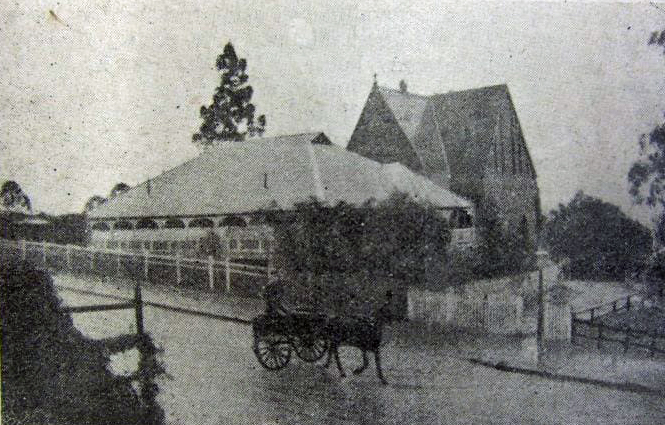

A few months later, work on the church commenced on the narrow allotments 2 and 3 down the slope from Vulture Street.

On St. Andrew’s Day, the 30th November 1878, Governor Arthur Kennedy, laid the foundation stone.

When the walls had reached a height of just 6 feet (1.8 m), construction ground to a halt for two years until more funds were raised. The church became known as “Smith’s Folly” after the Rector, the Reverend Frederick Smith, who was a driving force behind the project.

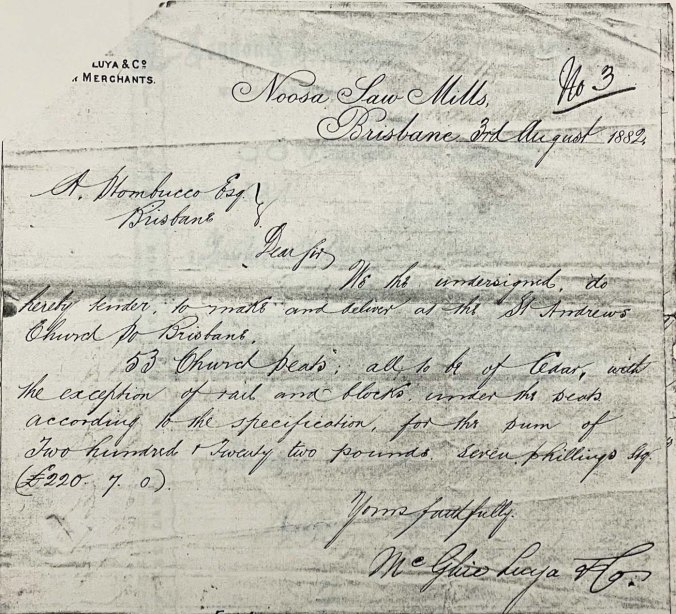

Recommencement of work in 1882 was marked by Bishop Hale ceremoniously laying the chief cornerstone. A bottle containing copies of newspapers and a document listing all concerned were placed in a cavity behind the stone.

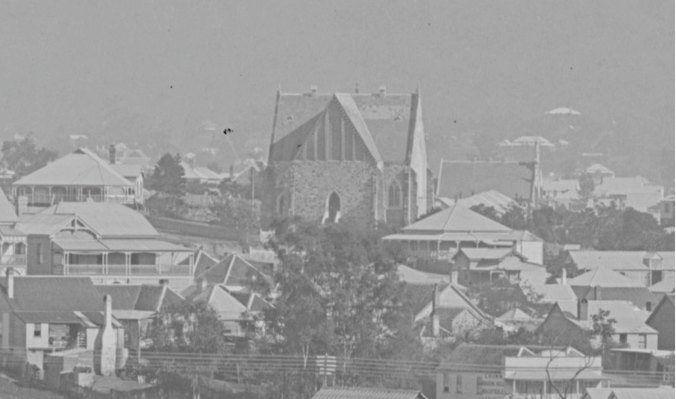

The church opened in June 1883. About half of the designed nave had been constructed.

With no rectory, alternate accommodation had to be found for the rector, at an extra cost to the parish of around £30 a year. In 1886 for example , the Reverend Dawes took up the role and found a house in Mortimer Terrace. This was a private lane running between Vulture and Sexton Streets opposite St. Andrews.

David Grayson junior

In 1887, Grayson’s youngest son David junior reached 21 years of age. Under the conditions of his father’s will, this triggered distribution of the remaining estate to him and his older brother John in equal parts valued at around £15,000 each. Their sister Jane had received £1,000 when she married 6 years earlier. In the split up, David took ownership of allotment 4 that St. Andrew’s parishioners had been waiting to acquire since the auction held 13 years previously.

David became well known around Brisbane and appeared in court at least 3 times, charged with reckless driving of a buggy. On two occasions, he seriously injured children.

In 1888, David junior married Jane Ross, and the marriage soon proved to be a disaster. Domestic violence inflamed by drunkenness caused Jane to leave her new husband several times, on the last occasion a month after she gave birth to a daughter, Eva. Grayson appeared in court charged with assault shortly afterwards.

Soon after, Jane decided on a divorce, and her brothers employed a private detective to gather the necessary evidence. This culminated in their breaking a window pane of his house in Leichhardt Street and thrusting a candle through the window to reveal Grayson and Appelina Brella, also known as Mrs. Cummins, in bed together.

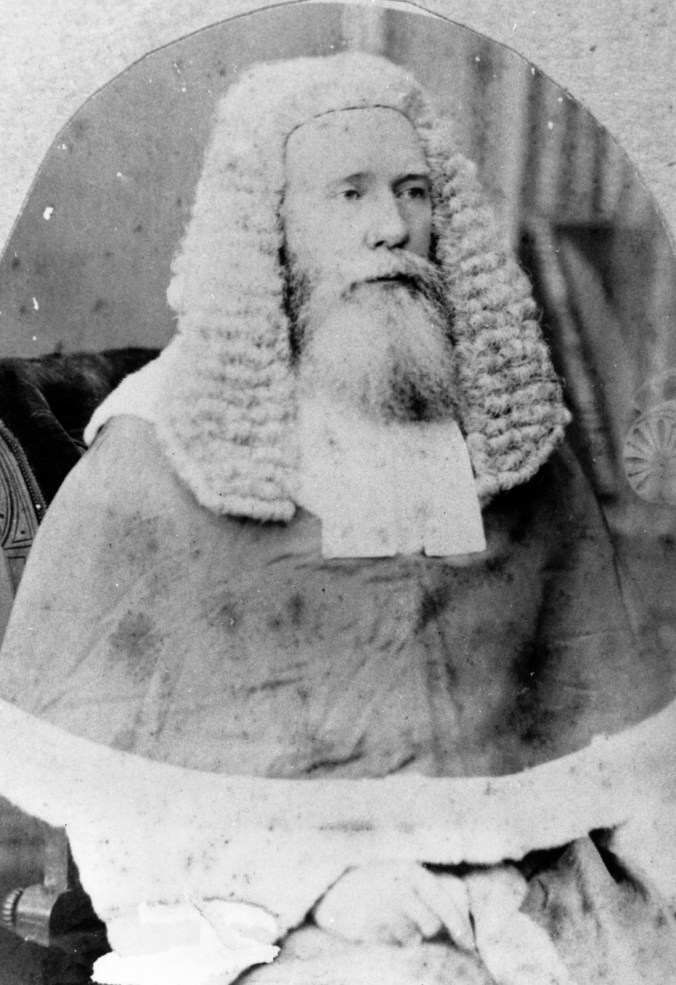

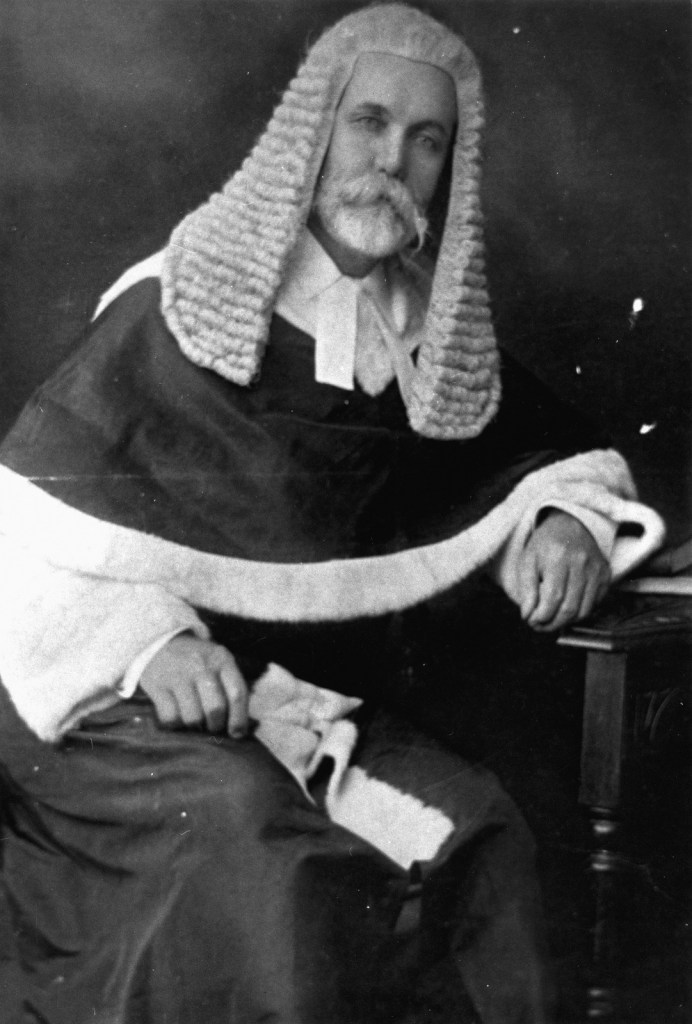

Judge Charles Lilley granted a decree nisi for dissolution of the marriage, to be moved absolute in six months, with Jane having custody of Eva.

As part of the divorce settlement, David Grayson transferred around £5,000 of his real estate, including his father’s home on Vulture Street, to a post-nuptial trust fund. His ex-wife Jane was to be the beneficiary unless she married again, at which time it would devolve to his daughter Eva. The trustees were David’s elder brother John and a tobacconist named Donald Campbell.

The post-nuptial agreement includes an affidavit from Jane stating that David had “dissipated and spent in debauchery and adultery all his means” except for what had been transferred to the trust. He was penniless and living in Townsville. In 1891, a now divorced 24 year old David was working as a stockman at Inkerman Station near Bowen. He died after falling off a horse and hitting his head. He left what remained of his estate to his brother John.

John Grayson

John became the only trustee of the post-nuptial trust soon after its establishment. The other trustee, Donald Campbell, committed suicide by shooting himself in the mouth at his shop in Queen Street. He had been in financial difficulties.

John took advantage of this situation by selling most of the trust properties and lending himself £1,375. For more of the Grayson story, see the appendix to this post.

The rectory is built

In June of 1888, David had transferred allotment 4 to his brother John. It’s probable that John offered to sell it to the parish soon after, as in September the Diocese Council approved a loan of £500 to purchase the land. The high price reflects the land boom which was then at its peak.

The transfer eventually occurred a year later. In August of 1889, Diocesan architect John Buckeridge called for tenders to build the rectory. It was completed soon after.

In 1910, the hall was completed at a cost of £1,000.

With a growing congregation, extension of the half built church became essential, and fundraising began in earnest in 1914. The war intervened, delaying progress. In 1932, the church nave finally reached its originally designed length. The church barely fits into the narrow location where, in 1875, Grayson’s intransigence forced its construction to commence.

In 1988, the rectory was sold and moved to Eight Mile Plains.

In 2003, the house changed hands again, and was relocated to Pullenvale where it was restored. The land that the parish took 13 years to acquire is now used as a parking lot.

Appendix – More on the Grayson family

David Grayson Senior’s daughter Jane married Warwick pharmacist Christopher de Lacy Clarke in 1881. He was prone to heavy drinking and left her to live with another woman in Sydney. She divorced him in 1891 . Clarke married again in 1893 but in 1902 he committed suicide with morphine.

Jane Ross Grayson remarried in 1890, and the proceeds of the divorce settlement passed to her 2 year old daughter Eva. John Grayson turned out to be an untrustworthy trustee. Despite the requirements of the trust, he was not transferring regular amounts for his niece Eva’s maintenance and education. In 1891, Eva’s uncle John Ross and a family friend Alfred Pryor took the issue to court6. Judge Patrick Real appointed Pryor as Eva’s legal guardian and ordered Grayson to pay him £40 a year, including the amount in arrears.

Seven years later, Pryor was once again before Judge Real, as Grayson had still not paid a penny for Eva’s support. The judge ordered that Eva’s uncle John Ross and guardian Alfred Pryor replace Grayson as trustee of the post-nuptial trust. I have not yet discovered the eventual outcome.

In 1909, Eva married Joel Goldman. Joel had recently arrived in Australia, and had been passing himself off as an American. On their wedding certificate, he correctly gave his parents’ names as Barnet and Esther, but stated that his birthplace was New York City, whereas he was born in Hull, Yorkshire. He was possibly covering up a previous marriage. He’d also been convicted of stealing a cheque book and large number of postage stamps back in 1899.

In 1910, their only child, Roy Grayson Goldman, was born. Joel travelled back to England in 1912 taking 2 year old Roy with him. Later records show his wife as Lucy Goldman, but they may not have married.

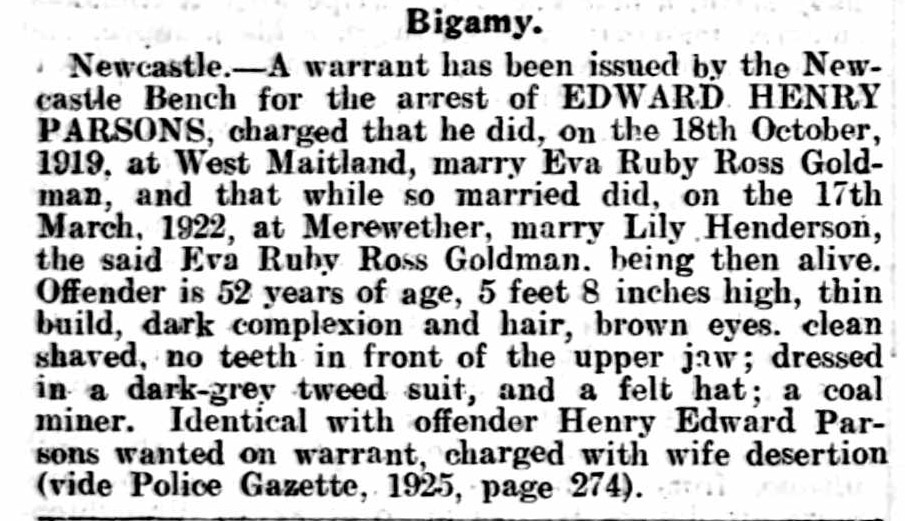

In 1919 Eva married Edward Parsons at West Maitland NSW. He left her and in 1922 supposedly bigamously remarried. However, I have not found a divorce record for Eva and Joel, and her marriage to Parsons was probably bigamous. When, in 1933, Parsons finally appeared in court on the charge of bigamy, the case was dismissed due to a lack of witnesses. I haven’t been able to trace Eva’s later life.

Eva and Joel Goldman’s son Roy Grayson Goldman, who had returned to England with his father as a 2 year old, was a Flying Officer in the RAF during World War 2. He was killed in 1944 along with 566 others when a German V2 rocket hit the Rex Cinema in Antwerp. Roy had married Lilly Barnett a few years previously, but the couple had no children. Joel Goldman passed away in 1946.

References

Most references appear in the text as hotlinks.

- Smith, H. W., & Trethewey, J. M. (2000). The Allens and the Graysons / by Heather W. Smith and Jillian M. Trethewey. H.W. Smith & J.M. Trethewey.

- St. Andrews Anglican Church Records (n.d.). State Library of Queensland

- Wetherell, E. W., & St. Andrew’s Church of England. (1979). The story of St. Andrew’s, South Brisbane. St. Andrews Church of England. State Library of Queensland

- [Souvenir booklet] / St. Andrew’s Church of England, South Brisbane. (1959). St. Andrew’s Church of England. State Library of Queensland

- Queensland State Archives, Item ID ITM2678269 GRAYSON David; GRAYSON Jane Ross post-nuptial agreement.

- Queensland State Archives, Item ID ITM94957 Equity File Eva Ruby Ross Grayson

© P. Granville 2025

Paul, gre

LikeLike