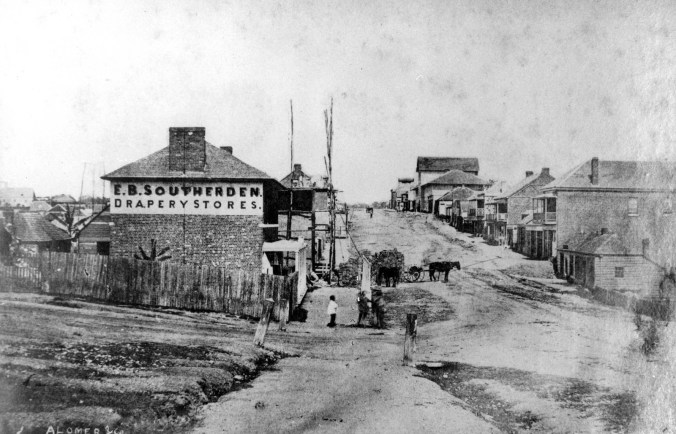

Brisbane in 1853

In 1853, eleven years after the commencement of free European settlement, Brisbane was a small town. The population was around 3,000 Europeans plus an unknown number of First Nations people, Chinese indentured labourers, and others not counted in censuses.

When in late March a group of convicts who had escaped from Norfolk Island started rampaging around Moreton Bay, it caused a sensation. The Moreton Bay Free Press cheekily commented that

The excitement in town on Wednesday and Thursday was such as has not been witnessed by the oldest inhabitant. It was actually possible to see four people in the streets together and many and conflicting were the rumours.

But let’s have a look first at Norfolk Island, where the story begins..

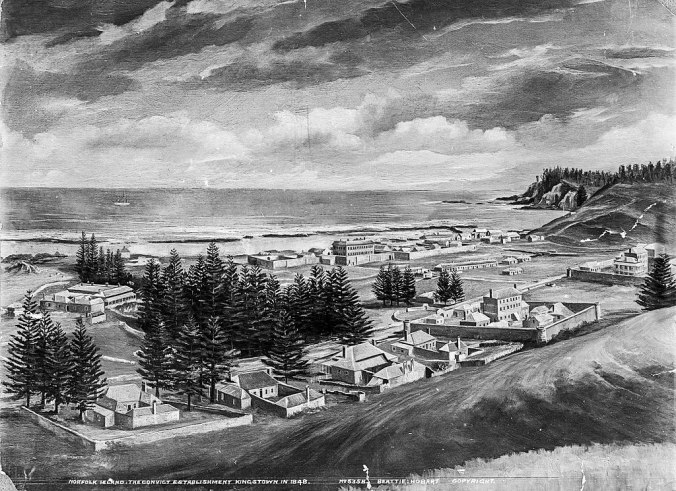

Norfolk Island

Captain James Cook came across and named Norfolk Island in 1774. At that time it was not inhabited, although archaeological evidence points to Polynesian occupation from about 1150 to 1450. The first convict settlement was established in 1788 and was shut down in 1814. In 1825, the convict station was reactivated under the same plan for new places of punishment for reoffenders that saw Moreton Bay established.

Stories of excessively brutal and inhumane treatment of convicts reached the mainland from time to time. In March of 1852, the concerned Robert Willson, Roman Catholic Bishop of Tasmania, made his third visit to the island. He wrote a report for Lieutenant-Governor Denison. Robert Hughs described the report in his book “The Fatal Shore”1.

It described mass floggings, blood-soaked earth, and an atmosphere of “gloom, sullen despondency, despair of leaving the Island.” He saw hideously overcrowded cells, men loaded with 36-pound balls on their chains, wizened pallid creatures staring at him “with their bodies placed in a frame of iron work.” He found the sole medical officer so much in cahoots with Price (the Commandant) that he claimed a desperately sick prisoner had to be kept in an airless cell because ventilation would be “prejudicial” to him.

It was no wonder that prisoners were driven to escape or mutiny. One such escape took place in 1853.

The escape

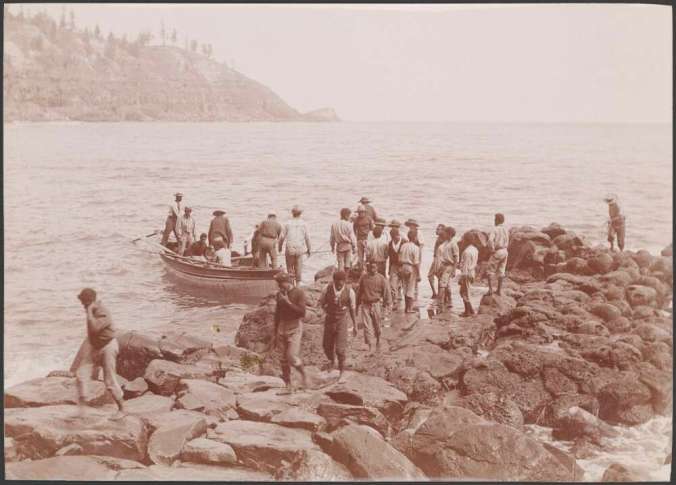

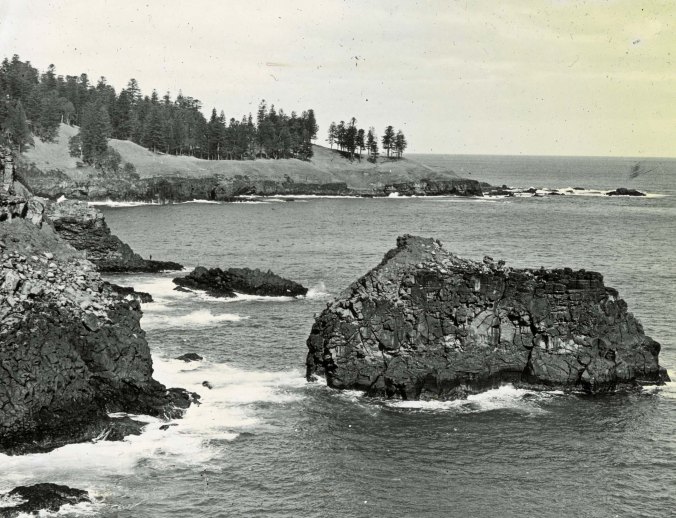

Norfolk Island lacks a harbour, and boats were used to transfer passengers and cargo to and from ships anchored off the coast. This was the only means by which people and goods arrived and left until an airfield was built in 1943. Convicts were put to work rowing the boats to and fro and handling cargo.

John Forsyth, a coxswain, described the events of the 11th of March 1853 in a subsequent court case. The barque Lord Auckland was being unloaded using a large boat known on the island as The Launch. On this occasion it was crewed by 9 convicts, accompanied by 3 armed soldiers of the 99th regiment, 4 constables who were trusty convicts, and Forsyth the coxswain in charge of the boat. They had just unloaded 6 passengers and some cargo.

It was evening, and the boat was about to return to the ship for the night to allow an early start at unloading the next day. The anchor had become fouled, and the coxswain asked the convicts to all come aft in an effort to free it with the next swell. In what was a prearranged plan, the convicts overpowered the soldiers, seized their weapons, and rowed along the shoreline in the twilight.

After rowing 3 or 4 kilometers, they came close to the shore among the rocks and ordered the others off the boat. Before all could get off the convicts thought that they saw another boat, and set sail with one constable still on board and the coxswain hanging on to an oar for grim life after being hit by it. They pulled him aboard and headed off to the west. On the boat there was just 11 pounds (5 kilograms) of bread, and some sugar, butter and tea. There was no compass.

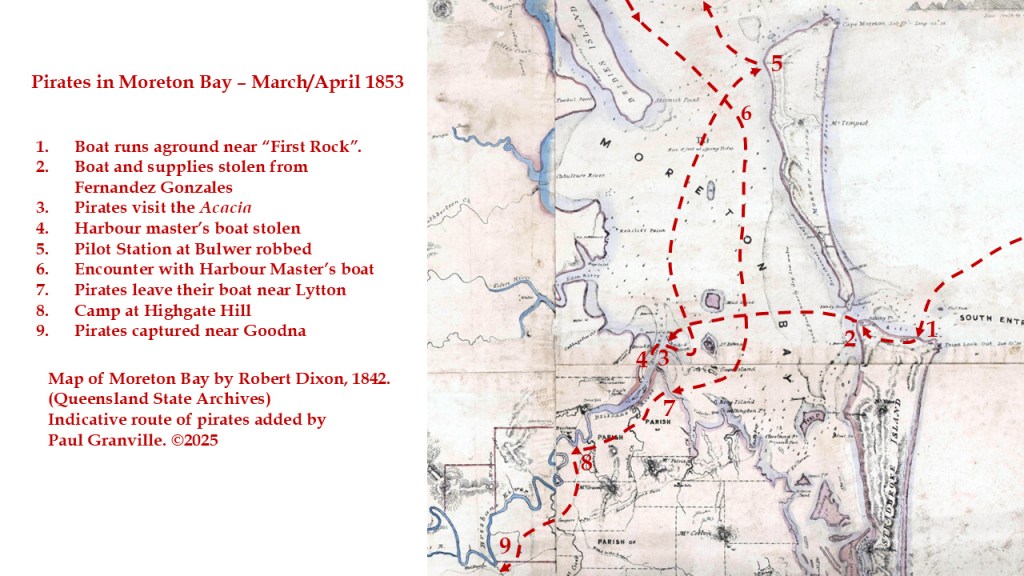

The Pirates in Moreton Bay

The arrival (map reference 1)

It took the runaways 14 days to sail the 1,400 kilometres from Norfolk Island to Moreton Bay, and they had been becalmed for 6 of those. At around 7 in the evening, after passing Point Lookout on Stradbroke Island, they came close to shore at what was described as “First Rock”, most likely today’s Adder Rock (Map Reference 1).

Two of the convicts swam to the beach to speak to some First Nations people asking where they could find water and Europeans. The boat became unseaworthy after it ran aground in the surf forcing the oakum sealant out of her seams.

Attack on Fernandez Gonzales’ camp (map reference 2)

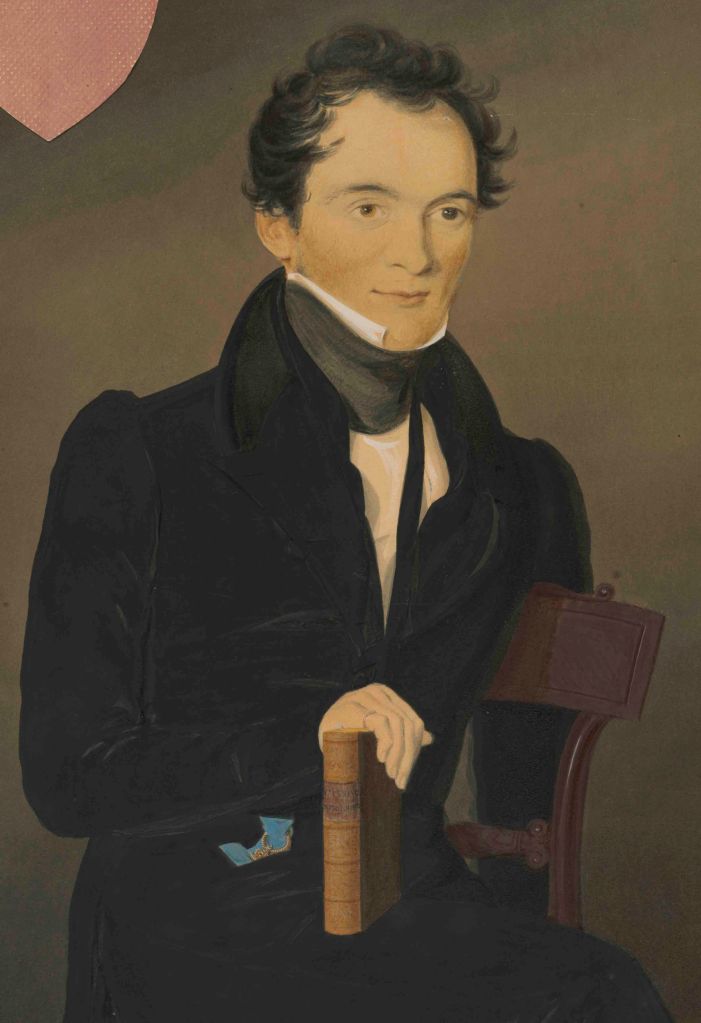

Fernandez Gonzales was born in Manila in 1822. He was one of a group of sailors tried in 1848 for disobeying the Captain’s orders on route to Sydney. He came to Brisbane where he joined the boat crew at the Bulwer Pilot Station. Before long, Fernandez had settled at Amity Point where he caught dugongs and turtles. He married a local woman named Juno, and they had 6 daughters.

There are numerous variations of the story of what happened at Amity. I have based my description principally on the testimonies of coxswain John Forsyth and Fernandez Gonzales in two different court cases, which substantially agree.

After their boat ran aground, all but one of the convicts followed the directions they had been given to Amity Point. Robert Mitchell stayed behind with the coxswain and constable. As soon as the others had gone, he told Forsyth that he wanted to give himself up.

Mitchell had been an inspector of police before being sentenced to transportation for the forgery of a cheque. He ended up at Norfolk Island after further forgery in Hobart. He was the only convict not later found guilty of piracy.

There were usually around 150 people living at Amity Point, including a few non-Indigenous people such as Fernandez. The convicts tried to gain Fernandez’s confidence by masquerading as shipwrecked sailors, but he was suspicious, as only two were doing the talking while the others remained silent. However, he readily gave them food.

When, smelling a rat, Fernandez refused to lend them his boat to go to town for provisions, they pulled out their revolvers and told Fernandez to go to their grounded boat where their captain would explain things. Fernandez arrived there, and the coxswain Forsyth explained the real story. They returned to Amity as six of the pirates were leaving in Fernandez’s boat. They had stolen food, clothing and a gun, and fired warning shots as they left. Three of the nine convicts had been left behind.

A few days later, a fisherman by the name of Timothy Duffy arrived at Amity, and he took the constable, coxswain and three convicts back to Brisbane. Fernandez, anxious for the pirates to be captured, sailed to Cleveland, and then walked the 25 kilometers to Brisbane to give his evidence to the police.

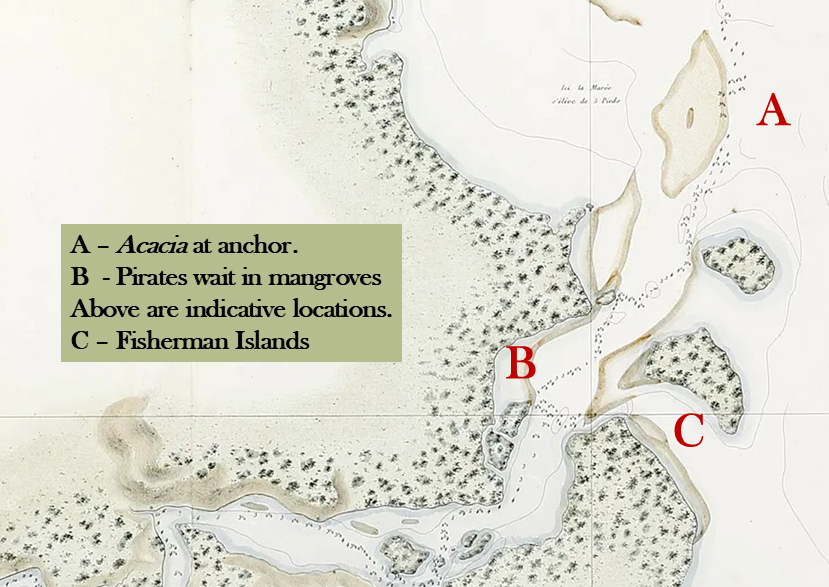

Bluff on board the Acacia (map reference 3)

The next morning the pirates brazenly boarded the barque Acacia moored near the river mouth, again passing themselves off as shipwrecked sailors, and were invited to breakfast (map reference A below). They had disguised their distinctive convict clothing by wearing it inside out.

While they were enjoying their bacon and eggs, the pirates watched the customs boat with six armed constables row past, setting off to fruitlessly search for them. On board the Acacia were some of the Harbour Master’s crew, who had just guided the ship out into the bay. After asking about the entrance to the river, the pirates set off knowing that before long, the Harbour Master’s men would be returning in their boat. They rowed a short way up the river and hid in the mangroves near Luggage Point, (map reference B below).

Theft of the Harbour Master’s boat (map reference 4)

When the Harbour Master’s boat passed on its way back to Brisbane, the pirates quickly rowed out from their hiding place. Pulling out their pistols, possibly not loaded, they forced the crew to change boats. They also donned the crew’s clothing, leaving them with convict uniforms. The pirates disappeared around Fisherman Islands (map reference C), making the Harbour Master’s crew believe they were heading south to Cleveland.

The pirates took all the oars, and the Harbour Master’s crew made their way upriver using pieces of wood to paddle. After a laborious journey to Brisbane, wearing convict clothing the hapless crew were placed under arrest until they were recognised.

Robbery under arms at Bulwer (Map Reference 5)

The pirates’ next stop was Bulwer on Moreton Island, where the Pilot Station had been based since 1848.

This time their story on arrival was that they were searching for a group of men in a boat who had that morning robbed people on their ship of £200. This seemed plausible to pilot Captain Watson as he had seen a strange boat, and he invited the pirates into his house. Once inside, they pulled out their weapons and ransacked the house for clothes, money and provisions, including Watson’s supply of rum. One report mentions that “they indulged in a slight carouse before they left the place“. Perhaps this put them in a cheery mood, as they agreed to the pilot’s pleading to be left a bottle.

Some of Watson’s children were returning to the house, and the pirates shot at them when, confused, they didn’t stop when ordered to. Fortunately, no one was injured. Captain Watson was very glad that the female members of his family were visiting Brisbane that day.

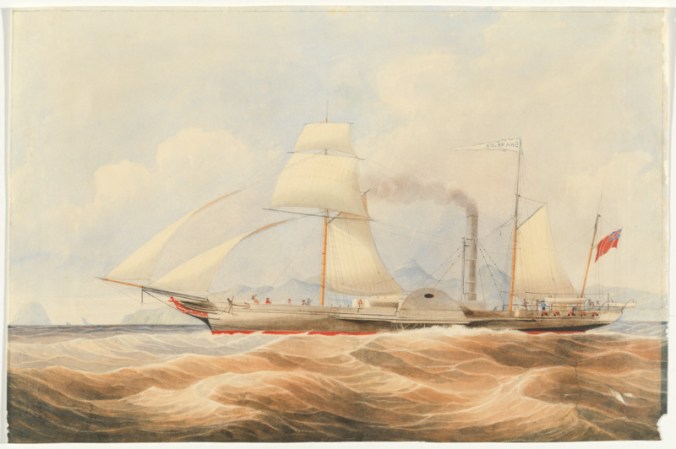

Before leaving, the pirates staved in the side of the pilot’s boat, but Watson was able to make repairs and sailed to Brisbane to report the crime. Captain Wickham, the Government Resident, took control of the paddle steamer Swallow, which had been about to head up to Ipswich. Its departure to search for the pirates was delayed as the engineer refused to go, and a replacement had to be found.

The search was fruitless, and the general opinion was that the pirates had left Moreton Bay, skirting around the top of Moreton Island via Freeman’s Channel, and were heading south towards the Tweed. The pirates had, however, headed north to Wide Bay.

Wickham offered a reward of £60 for any free person “who shall cause the said Convicts to be apprehended“. In the event that a convict offered the information, Wickham would recommend that the Governor award a conditional pardon. Months later, the Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land offered a further £100 reward, but by then the pirates were all in custody.

The chase (map references 6-9)

Some weeks after the Bulwer incident, the pirates were back in Moreton Bay. They later said that they had sailed to Wide Bay where one of their number had been before, but had received such a hostile reception from the local inhabitants, that they turned about and returned.

They were spotted one evening and the next day, close to Bulwer, found them close to one of the Harbour Master’s boats. They unconvincingly tried to pass themselves off again as shipwrecked sailors, and one of the pilot’s men, “Joe the Frenchman“, took a shot at them but missed.

The steamship New Orleans had anchored at the mouth of the river a week earlier to reload with coal. She was on her way from San Francisco to Sydney carrying men eager to try their luck on the Australian gold fields. A party of armed volunteers from among the passengers set out to search for the pirates but had no success.

A few days later Eugene Lucette, a fisherman, turned up with the Harbour Master’s boat that the pirates had stolen. He’d seen them haul the boat up in the mangroves near Lytton and disappear into the bush. Lucette was one of 15 convicts sent from Mauritius to Moreton Bay in 1840. He obtained his Certificate of Freedom in 1847.

A posse was assembled by Water Police Magistrate William Augustine Duncan, who also fulfilled the roles of Sub-collector of Customs, Guardian of Minors, and Immigration Commissioner. It was guided by indigenous trackers and included Chief Constable Sneyd and his men, as well as volunteers including Fernandez Gonzales, who was looking for revenge.

The pursuit was something of an anticlimax. Welsby2 describes how after two days, the trackers led the posse to Highgate Hill where they found the pirates’ camp fire. They were following the ancient Aboriginal pathway to the Goodna district, which later became Hampstead and Gladstone Roads.

Guided by the trackers, they found another campfire with signs that the pirates had shot, cooked and eaten ducks from the Yeronga lagoon.

The next day, the 13th of May, the pursuers caught up with the six pirates. Weakened by lack of food, they gave up without a fight, much to the chagrin of Fernandez, who was hoping for a revengeful shootout. Welsby2 says that they found the escapees near Bundamba. However, contemporaneous newspaper reports say it was around 8 miles (13 kilometres) from Brisbane, or close to Wacol, more likely given that the weakened pirates were on foot.

Trials and tribulations

The convicts captured in March

The three convicts who had been captured at Amity Point some 13 weeks earlier had been held in irons at Brisbane Gaol before being sent to Sydney. One, an Irishman named Clegg had tried to escape at Amity but had been quickly recaptured. They were to be tried in Hobart, as at the time Norfolk Island fell under the control of the Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land.

On the way from Sydney to Hobart, their ship was forced to take shelter from bad weather at Twofold Bay. James Clegg again managed to escape from his shackles and swam some 5 kilometres to shore. It was thought that he had drowned, but a policeman at Port Albert, Victoria, recognised him months later. He had one last attempt at escape coming up the Derwent to Hobart, when yet again he managed to escape from his shackles.

The other two, Dennis Griffiths and Robert Mitchell, were tried at Hobart for escaping, and “piratically stealing a launch, three pistols, three bayonets, three coats, thirteen casks, ten blankets, sails, &c, the property of her Majesty.”

Robert Mitchell, who maintained he was an unwilling participant, was supported by the testimonies of both the coxswain John Forsyth and the convict constable George Boardmore. Boardmore appeared in court dressed in his “Magpies”. Mitchell was found not guilty while Griffiths was sentenced to be transported for life, to be worked in heavy irons in a quarry gang for the first year.

The 6 convicts captured in May

Coincidentally, the Brisbane Assizes were held the week after the remaining 6 convicts were captured near Goodna. Roger Therry, the NSW Chief Justice, presided and the Attorney General John Plunkett prosecuted. At that time, the old male convict barracks were used for court sittings.

There was confusion about the identity of the 6 convicts. Although it was almost certain that they all had existing heavy sentences, “for more abundant caution” Plunkett decided to try them for the first crime committed at Amity Point. Jeremiah Sullivan, Jacob Cooper, James Godfrey, John Meek, Joseph Davis, James Merry, and Thomas Claydon were indicted for “stealing from the person of Fernando Gonzales, at Amity Point , on the 25th March last, one whale-boat, one gun, 100lbs. flour, two shirts, &c. ; they being then and there armed, with certain offensive weapons, to wit, pistols“.

All 6 were found guilty and sentenced to be transported beyond the sea for 15 years, which was the lightest sentence for such a crime. It would have meant little due to their previous sentences. Thomas Claydon, for example, had already been sentenced to life imprisonment three times.

More trials

Late in 1853 there were further trials in which the ex-pirates were sentenced to life for stealing the boat and stores from Norfolk Island and assaulting John Forsyth the coxswain, “putting him in bodily fear for his life“. Some of them were further sentenced in a magistrate’s court to 4 years hard labour in chains .

Further escapades

Seizure of the Lady Franklin

The Lady Franklin was a barque built at Port Arthur in 1841. It was named after Jane Franklin, well known as an explorer and philanthropist, who was the wife of the governor of Van Diemen’s Land at that time, Sir John Franklin. It was frequently used to carry stores, convicts, soldiers, and others to and from Norfolk Island.

The Lady Franklin left Hobart for Norfolk Island on the 16th of December 1853 with 22 convicts on board, including the 9 Moreton Bay pirates. They were accompanied by a sergeant and 10 soldiers from the 99th Regiment.

Twelve days later, the convicts rebelled and took control of the ship. They had laboriously cut through a 3 inch (7 cm ) plank of eucalyptus hardwood with the handle of a tin pannikin, enabling them to escape from their lock-up and appropriate arms stored on deck.

Captain Willett was unconscious for a day after being given a severe blow to the head. They sailed for 11 days, and having failed to capture the passing schooner Emily Hort, were running short of water. Near Fiji, the convicts left the Lady Franklin in the ship’s boat and cutter. They cut the ship’s rigging and broke the chronometers to prevent a chase.

The Lady Franklin limped back to Hobart under the command of Captain Willett, who had injuries including a broken shoulder as well as several teeth knocked out. Hobart was soon awash with rumours, especially regarding the behaviour of the soldiers. One newspaper reported that

“some say they were hocussed by a woman on board, and rendered all but insensible; but from whatever cause, they almost to a man failed to render assistance“.

Sergeant Allan, who had been in charge of the soldiers, was court-martialed along with a few of his men. He had surrendered after the convicts threatened to murder “every man, woman and child” on board. The trial lasted for 8 days, and a decision wasn’t announced for two months while the soldiers waited in jail. Allan was reduced to the rank of private with a recommendation for clemency. He was later reinstated. The scapegoat was Private Michael Durr who was sentenced to transportation for life.

Rounding up a few of the escapees

In 1852, HMS Herald arrived in Australia to undertake survey work in the South Pacific. There is an interesting connection with the Lady Franklin, as in 1848 the Herald had searched for Sir John Franklin’s missing expedition that had been exploring the North West Passage. In 1854, the Herald was used to survey the waters of the Fiji Islands.

At Levuka, the crew found one of the boats of the Lady Franklin, and “Ginger” Merry gave himself up. Two of the other Moreton Bay pirates, Joseph Davis who had been the ringleader, and Denis Griffiths, fled to Naviti with two Fijian women. They were taken into custody after the locals were given what was described as a ransom of a barrel of gunpowder and five muskets.

Griffiths managed to escape, but in February of 1855 Merry and Davis faced the court in Hobart.

All of the witnesses who had been on the Lady Franklin testified that the two had moderated the actions of others who wanted to murder all on board. Merry spoke quite eloquently in his own defence, citing the injustices meted out to him on Norfolk Island by Commandant Price. Price had become infamous for “the morbid ferocities of his rule”.

Despite all of this, they were both condemned to death with a recommendation for clemency. Later their sentence was reduced to 6 months with hard labour at Port Arthur. The other six Moreton Bay pirates were never heard of again.

Appendix – the story of John Meek

Detailed records were kept of convicts transported to Australia. Rather than summarise the records of each of the nine involved in this story, I have selected one to illustrate the lives of these men who ended up in the hell hole of Norfolk Island.

From soldier to convict

John Meek was a private in the 54th Regiment of Foot based in Dublin where in 1843 he was court-martialed for desertion. He was sentenced to 14 years imprisonment, and transported to Australia. The records also mention an extension of 9 months for being drunk on duty and a punishment of 100 lashes for desertion.

Convicts were identified by the ship and year of transportation and his label was Orator, 1843. Meek arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in November of 1843.

Description

Convict records give a detailed description and Meek’s is as follows.

House servant, Height 5’5″ (165cm), Age 21, sallow complexion, oval head, dark brown hair, no whiskers, round visage, medium height forehead, dark brown eyebrows, light brown eyes, broad nose, medium mouth, medium chin, home place Crecy Common near Buckingham.

Remarks -large scar on left eye, mermaid with comb and glass with 50 in it, two bottles glass, rose, John Holmes, 2 crosses and 5 dots, Caroline Rogers, skull and crossbones, flag, goblet, 1838 and heart on left arm, skull and crossbones, coffin with E on it, flower pot and flowers, JH, woman, on right arm, foul anchor and capstan, JH enclosed in wreath, , rings on 2 middle fingers right hand, anchor, JM, CR, body of a woman, 1840, heart 2 rings on middle finger left hand. D on left side.

Surgeon’s report (on the voyage): No offences; employed as Boatswain. General conduct, very good, an active chief constable and good disciplinarian.

Punishment in Australia

- 1844 Absconding – 6 months of which 3 months hard labour in chains

- 1845 Neglect and willful mismanagement of work – 14 days hard labour

- 1846 Larceny 5 pounds – 6 months hard labour

- 1846 Absent without leave – 6 months hard labour in chains

- 1846 Misconduct in making use of improper laugh – 48 hours solitary

- 1847 Absconding – 12 months hard labour in chains added to existing sentence

- 1847 Misconduct defacing and severing work – 14 days solitary

- 1847 Making use of obscene laugh to a watchman – 6 days solitary

- 1847 Misconduct in behaving disrespectfully towards an order – 14 days solitary

- 1847 Misconduct in being dressed at back of his sleeping berth and having a leg iron broken – 14 days solitary

- 1849 Absent without leave all night – 3 months hard labour

- 1849 Absconding – 4 months hard labour

- 1849 Misconduct in giving the name of another man as his own – existing sentence extended 6 months in chains

- 1850 Misconduct in being absent from work on a pretext of sickness – reprimanded

- 1850 Burglary at Oatlands, putting in fear Thomas ? and William Rawlings with menace and threat – sentenced to death but commuted to life transportation and sent to Norfolk Island for 10 years.

Meek along with four others had absconded from Tunbridge Station and had a short career as bushrangers before being apprehended by three constables. His punishment on Norfolk Island is not recorded but is likely to have included lashing, solitary confinement, working in a chain gang and time on the treadmill.

- 1853 Piracy – 2nd life sentence, 4 years hard labour in chains

- 1854 Absconded after taking part in the seizure of the Lady Franklin.

References

Most references appear as hotlinks in the text.

- Hughes, Robert “The Fatal Shore” Collins Harvill, London 1987, Page 549.

- Welsby, Thomas. edited A.K Thomson “The Collected Works of Thomas Welsby” Jacaranda Press, Brisbane 1967, Volume 1, page 281.

© P. Granville 2025

GREAT ARTICLE THANKS Paul – from Ray Pini

https://pctingalpa.com.au/our-history/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the snippet of history that touchs on Highgate Hill Paul.

When i walk down Boundary Street I see the descendants of those pirates and other rogues in the street; thin, short, suntanned and wizened, often with life’s damages showing as vividly as their tattoos.

In 1985 I was renovating in Newtown, Sydney. If I had stayed in that building as you have done in Dornoch terrace I would hope to have had as thorough an inventory of its history as you have of yours. The care paid to details in plaster and wood is, I think, the spirit from the past, for example, in those carved brackets. At a current hourly rate and using hand tools, how much would a carpenter need to charge you today? $100s of dollars per set I think. And where would he source the timber?

Warm regards

John Cleary

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thankyou so much for another fascinating and well researched article.

I have an ancestor Joseph Genders who was sent to Norfolk Island 1791 and left for Tasmania in 1808. I am beginning to do some research into his story.

https://peopleaustralia.anu.edu.au/biography/genders-joseph-31420

Thanks again

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much for your comment . It looks like you have some very interesting research ahead of you.

Paul

LikeLike