Various astrological sources state that Sagittarius rules the thighs and legs. Charles Julius Jones was born on the 13th of December, making him a Sagittarius. Whether you believe in such things or not, Charlie’s life was certainly ruled by his legs, in hapless and eventually tragic ways.

Early days

Late in 1883, Phillip and Teresa Jones and their 3 children Lucy, Ada and Hamilton arrived in Brisbane from England on the steamer Nuddea . A year later Charles Julius was born at Rosewood. By 1889, they were living in the West End area, and Hamilton and Charles were enrolled in the West End State School. In 1889, Mary Ann gave birth to another son William, and in 1894, the family moved to Carlton Street, Highgate Hill.

In 1899, Phillip Jones was visiting Gympie. He had been drinking at Dunlea’s Hotel, and became quite drunk. Coming out of the hotel, he fell heavily onto the road, and subsequently died with a fractured skull. A widowed Teresa didn’t have the money to go to Gympie for the funeral.

Charlie became known locally as a good swimmer. He worked as a newsboy to help support the fatherless family.

Shark attack

In the middle of a 32 degree January day in 1902, Charlie, one of his brothers, and a few mates crossed over Dornoch Terrace from Carlton Street and walked down the slope to the river for a swim off the rocks.

It was common for boys to do this, and my grandfather told me that he often swam in the river at about the same point in time. As described in my post “Making a Splash“, in 1902 the nearest public swimming pool was the Metropolitan floating baths at the end of Edward Street. Not only was it far away, but also the boys were unlikely to have been able to afford the three pence entry.

The other boys had left the water when Charlie cried out that he had been bitten by a shark. He made it back to the shore and was rushed to Davies Pharmacy at West End which served as an unofficial community first aid centre. When Davies saw that the flesh and sinews of Charlie’s left calf had been badly torn by the shark, he phoned the ambulance.

Charlie recovered from his injuries after treatment in the General Hospital. He became a successful member of the South Brisbane Swimming Club that was based at the baths built in 1902 at Kurilpa Point. He was also known as a promising boxer.

Hamilton Jones goes to war

In July of 1914, the British Imperial Government declared war on Germany, and Australia as a dominion was also automatically at war. In September, Charlie’s older brother Hamilton enlisted, and in May of 1915 landed at Gallipoli with the 2nd Light Horse. A week later, his thumb was blown off and he was invalided back to Australia.

Hamilton was a sawyer and Secretary of the Timber Workers Union. He was one of 13 members of Queensland’s now defunct unelected upper house, the Legislative Council, nominated in 1917 by Premier Ryan to allow his legislation to be passed. In 1922, they voted themselves out of existence.

Marriage and enlistment

Charlie worked as a storeman at the Brisbane Milling Company on the river at Stanley Street, South Brisbane.

At some stage he had gained the nickname of “Chinchilla”, usually contracted to “Chiller”.

He was living with his mother, who by 1913 had moved to Watford Terrace in Browning Street.

At the end of January 1915, Chiller married Mary Ann Parsfield at the People’s Evangelistic Mission House on Leichardt Street, Spring Hill. In July, just 6 months later, Chiller enlisted in the army. Australian troops were still fighting at Gallipoli, and there was a surge in recruitment. At the time, he would have heard of Hamilton’s wounding.

Chiller’s medical examination gives his height as 5′ 8½” (174mm) and his weight 130 lbs. (59 kilograms) and notes a large scar on his right leg. At almost 30 years of age, he was considered “middle-aged”, and older than most of the other volunteers.

Chiller was part of the 11th reinforcements of 15th Battalion, which was made up largely of Queenslanders. The battalion had gone ashore at Gallipoli on April 25th and was still there when Chiller departed on the troop transport Seang Bee in October.

The Seang Bee arrived at Alexandria at the end of November, 1915. Just a few weeks later, British forces evacuated Gallipoli and returned to Egypt. Chiller went into training. The troops that had fought at Gallipoli were resting and regrouping and he was posted to “A” company of 15th Battalion.

Pozières

The 15th sailed for Marseilles in June of 1916 on the Transylvania, a former liner. The following year she was sunk by a German U-boat with the loss of 412 lives.

The Battalion headed north to the battlefields of the Somme. Before going into action, men of the 15th were trained in trench warfare. Chiller was selected to be a “bomber”, or grenade thrower.

These men were chosen for their strength, as not only were they required to throw the 765g Mills Bomb as far as possible, but they also carried a load of bombs. Chiller’s strength from boxing training would have come to the fore.

At Pozières, the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Australian divisions captured and held a strategic high area, with an appalling 23,000 men killed, wounded, or taken prisoner over 42 days. These losses over a few weeks were similar to those of over 8 months on Gallipoli.

In early August, 4th Division, including 15th Battalion, moved up to the front line under cover of darkness to relieve 2nd Division, which had suffered many casualties. The German artillery were laying down a heavy barrage. Confused in the dark, the guides led Chiller’s “A” Company into barbed wire. Sergeant-Major Fleet later described the experience1.

Travelling through narrow trenches in full marching order, falling or walking on or slipping upon dead men, wire overhead, wire under foot, feet tangled in wire, wire around your neck, wire tangled in your rifle, or your gear, it was a hell of a night.

The 15th remained on the front line until early September. Towards the end of this period, they were involved in attacks on the heavily fortified German position at Mouquet Farm, where they suffered further heavy casualties. It’s hard for us to imagine today the conditions that they endured.

The large number of unburied dead lying about in the mud, their bodies swollen to outrageous proportions, emitted a stench equalled only on Gallipoli…So nauseating was the whole position that strong men were freely sick.2

In September, Chiller was promoted to corporal.

Wounded at Gueudecourt

In January of 1917, 15th Battalion was back on the front line near Gueudecourt. The Somme River was “one block of ice“, in what was the coldest winter for 80 years. Food delivered at night to troops on the front line froze before it could be eaten, with temperatures dropping to 12 below zero.

Here, the grotesque shapes of what were once human beings lay carpeted with snow. Some of them had become part of the frozen earth itself where they waited the warmth of spring and the burial parties.3

The Australians were tasked with keeping the enemy under pressure in preparation for a spring offensive. The Battalion war diary describes how on the 1st of February at 7pm, 226 men from “A” and “C” Companies attacked what was known as “Stormy Trench”, a key position in the German line. The attack was successful, with the capture of 52 prisoners.

Sergeant Farr and his bombers, including Chiller, were sent in to “mop up“. The Germans mounted a strong counterattack at 4.30am and Chiller and a few others were injured and unable to walk. Under a heavy artillery barrage, and with no bombs remaining, signal flares wet, and machine guns out of action, there was no option but to leave the wounded behind.4,6

Chiller’s Red Cross file includes several consistent eye witness accounts, such as the one below.

.

Prisoner of war

Chiller was taken prisoner and sent to a military hospital at Cambrai. This French town was occupied by German forces from 1914 to 1918.

Although later accounts mention bullet wounds to his legs, German records say that he was wounded in the right foot and thigh by hand grenade shrapnel.

By June, Chiller had recovered to the extent that he was transferred to a prisoner of war camp at Soltau in Lower Saxony.

In October 1917, Teresa Jones received a letter from Chiller, and as was common at the time, she sent it to a newspaper to be published. From this letter, it appears that he underwent an operation at Munster before being transferred to Soltau.

A few lines to let you know how I am keeping. I have left Munster Hospital, and I am very glad to say I am able to get about without the help of a stick, but my right leg is still weak. I am now at Soltau Camp. It is a lovely big camp. I expect to be getting about just as well as ever in a couple of weeks. My wounds have healed up wonderfully quickly. Dr. Holmon, of Munster, shook hands with me, and said I was one of the best patients he ever had. I am now receiving parcels of clothing and foodstuffs from the British-Australian Red Cross Society, also bread parcels from Copenhagen. I am well off for food, so don’t worry on that account. From your loving son, Charles Jones. Reg. No. 3338, Corporal C. J. Jones, 15th Battalion, AIF., Soltau, Lager 1, Baracke No. 35, Hannover. Deutschland, c/o Australian Red Cross Prisoners of War Department, 54 Victoria-street, London, S.W.

Repatriation

Following the armistice in November of 1918, prisoners of war were transported back to England. Chiller arrived on Boxing Day. Thomas Chataway5 recounts how members of the 15th Battalion in London gave a dinner to a large number of prisoners of war who returned in a bunch. It’s possible that Chiller was there.

In March, Chiller wrote to Bob Wilson complaining about the terrible weather, telling him of his travels around Britain, and that he finally had a sailing date. He commented that “My legs are as good as ever. I can walk as good as ever”.

Before leaving England, Chiller sent a photo to Bob. On the back he wrote “We just got these photos of our final booze up before leaving England, so excuse grins. I am your old pal Chiller. 16/3/19.”

In the photo are three others who sailed from Australia with Chiller on the Seang Bee over three years earlier. Joe Emerson had received severe gunshot wounds at Pozières in 1916 and was wounded again two years later at Amiens. Robert Ford, like Chiller, had been taken prisoner of war at Stormy Trench. Francis Gatley received severe gunshot wounds to the head in 1916, and a year later was one of 1,170 Australians captured by the Germans in the ill-planned First Battle of Bullecourt.

They boarded the Plassy in mid-March for the 40 day journey.

Back in Brisbane, Chiller was reunited with his wife Mary Ann, his mother Teresa, and others of his family after an absence of almost 4 years. For the previous few years Teresa and Mary Ann had been patiently waiting for Chiller’s return at Eva Villa in Vulture Street.

Chiller found work as a lift operator at the Treasury Building. A later newspaper article commented that “he was popular with his fellow employees, both by reason of the efficient manner in which he carried out his duties, and the romance attached to his long and strenuous period of active service“. Like most returned soldiers, he would have glossed over the horrors that he had witnessed.

He and his brother Hamilton both purchased war service homes built on McIlwraith Avenue, Norman Park.

Disaster

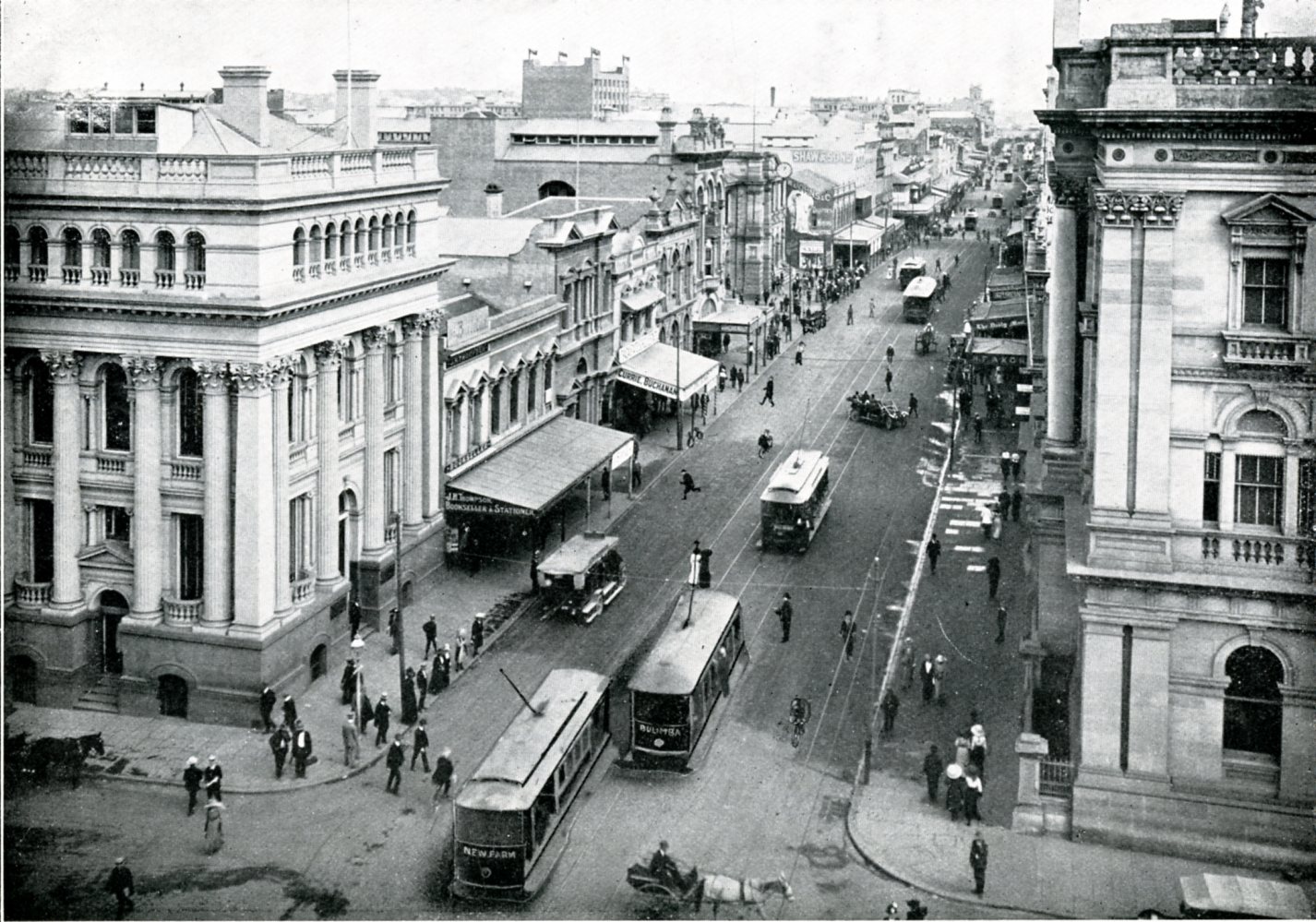

Chiller’s return to peaceful civilian life was unfortunately not to last long. Early in October of 1920, he jumped onto a tram that had already started moving down Queen Street from the Creek Street stop. Chiller slipped and fell into the arms of a mate and both fell onto the roadway. Chiller’s legs shot out onto the tram tracks and a wheel passed over both of his legs.

His right leg was almost completely severed, and the other had compound fractures. Initially, it was thought that he would not live, but Chiller survived with both legs amputated above the knee. He was to remain in hospital for 6 months.

Fund raising

Of immediate concern after his condition stabilised were the repayments on the couple’s war service home. These houses typically cost around £700, and with 5% interest, repayments on this amount were almost £50 a year for 25 years, .

Gavin “Guvie” Wilson was a Kurilpa local who described his occupation in the electoral role as “of independent means“. He was heavily involved in Rugby League and possibly knew Chiller from when he was a junior player. “Guvie” established a committee to raise funds to assist Chiller and Mary Ann, and it had its first meeting at the West End School of Arts a few weeks after the accident.

The committee, as well as advertising for donations, held a number of fund raising activities. The major one was a day long event at Davies Park in March of 1921, which included the first rugby league match of the season between two top teams, Wests and Valley, and school athletics races. In the evening, there was a “battle of the bands” involving 11 local brass bands.

Just out of hospital, Chiller was able to attend.

Despite the bad weather, there was a fair attendance. Valley defeated Western Suburbs 8 to 6 in the rugby league game, and Southport won the band contest.

By the time the fund raising efforts came to an end in June 1921, the committee had raised £672, allowing Chiller and Mary Ann to retain their home.

Fruit stall

By 1922, they were running a fruit stall at the gates of the Supreme Court in George Street, handily close to the Roma Street markets. Possibly Chiller’s wartime cobber Joe Emerson, who worked at the Court before and after the war, had pulled a few strings to help.

Chiller went through some hard times and was arrested twice for drunk driving. The first time was in 1927. A newspaper account entitled “Cripple Asleep In Sulky” mentions that he was carried into the court.

Jones had a drink, and went to sleep in his sulky. A constable roused him up, and then arrested him. The horse was standing, and there was no traffic about.

In 1929, he was fined the large sum of £5 for a similar offence.

In 1927, Chiller wrote a letter to the editor complaining that the new Brisbane City Council had restricted the 50% reduction in rates for servicemen on pensions that he had enjoyed under the previous South Brisbane City Council. He mentioned that their income from the fruit stall was only around 15 shillings a week, and their combined pensions amounted to £1/3/10½ . Their total weekly income was less than half of the basic wage which was £4/8/- in 1927.

Running the fruit stall wasn’t without its incidents. In 1927, a thief took some jewellery and a set of false teeth from Mary Ann’s handbag after distracting her.

The fruit stall was located under a huge jacaranda tree.

In 1935, a massive branch almost a meter in diameter, weakened by dry rot, came crashing down, missing the stall by inches. After a taxi driver shouted out a warning, a couple standing nearby ran for safety, receiving only minor injuries. Mary Ann had left the stall just minutes before to buy a casket ticket. She called it “a lucky escape“.

The heart of a lion

In his final years, Chiller became bed-ridden and suffered from a chronic gastric ulcer. Debilitated, in 1946 he died from pneumonia aged 61. In an obituary in a newspaper boxing column, Chiller’s long time friend Joe Emerson commented that “He had the heart of a lion. He never gave up, never failed to keep his chin up“.

Mary Ann passed away in 1956. She was buried alongside Charles.

References

- History of the 15th Battalion. Lieutenant T. P. Chataway. William Brooks & Co. Brisbane 1948. p119.

- ibid p133

- ibid p147

- ibid p152

- ibid p237

- Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918 Volume IV, Chapter 2 p 31.

© P. Granville 2024

What an incredible story.

LikeLike

Such stamina, determination and resilience demonstrated by Charlie. It is amazing that you were able to research and obtain all this detail about this man’s life in Brisbane and his overseas service. Thank You for such an enjoyable read.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Dianne Thanks very much for your comment. I’m glad you enjoyed reading Charlie’s amazing story .

LikeLike

A wonderful story of “Chiller” Jones, Paul and you have done a lot of research, congratulations.

I also published a story of “Chiller” in the Generation magazine of Genealogical Society of Queensland in June 2013 (Vol 35 No 4), which I titled ‘The Shoebox – a story of Charles aka Chiller Jones’ telling the tale from the contents of a shoebox I was handed following the death of my uncle, Harold Wilson. Harold was the son of Chiller’s mate, Robert Wilson and his brothers including Gavin, and prior to WW1 Robert & Chiller worked together at Brisbane Milling Company.

LikeLiked by 1 person