Today, Sunday is a day of leisure for many, with time spent shopping, eating out, playing sport, and on other leisure activities. This situation has evolved slowly over a long period from the position of any work or public leisure activities on a Sunday being an anathema to most people and often illegal. Along the way, there was angst, stale bread, and the ripping up of cricket pitches.

The sabbath

Observance of a day of rest every week was one of the twelve commandments which, according to the Jewish Torah, were revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai and inscribed by the finger of God on two tablets of stone. In the year 321, Emperor Constantine declared Sunday a day of rest in honour of the sun god Apollo. Constantine later adopted and patronised Christianity, and by 386, Sunday was being referred to as the Lord’s Day. Observance of this commandment became a central tenet of the Christian Church.

Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy.

Six days shalt thou labour, and do all thy work:

But the seventh day is the sabbath of the LORD thy God: in it thou shalt not do any work, thou, nor thy son, nor thy daughter, thy manservant, nor thy maidservant, nor thy cattle, nor thy stranger that is within thy gates:

For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that in them is, and rested the seventh day: wherefore the LORD blessed the sabbath day, and hallowed it.

King James Bible, 1611, Exodus 20:8-11.

The Lord’s Day in early Brisbane

Sunday was recognised as a day of rest from the beginnings of European settlement at Moreton Bay in 1824. It was the only day that convicts were not required to work.

Australian colonies inherited British acts of Parliament. Some acts, such as those dealing with witchcraft, night poaching, and the protection of stocking frames, were repealed in Queensland over the years. However many remained in force in Queensland until 1984.

A number of Acts of Parliament restricting Sunday activities were passed during the reigns of Charles I and II. One in 1625 stated that “There shale be no meetings, assemblies or concourse of people out of their owne Parishes on the Lord’s Day within this realme of England, or any of the Dominions thereof, for any sports or pastimes whatsoever”‘

The 1677 Sunday Observance Act stated that “noe Tradesman, Artificer Workeman Labourer or other Person whatsoever shall doe or exercise any worldly Labour, Busines or Worke of their ordinary Callings upon the Lords day or any part thereof (Workes of Necessity and Charity onely excepted)”.

Despite these laws, the attitude in Brisbane to the day of rest was often relaxed, much to the disgust of some in the community who wrote scathing letters to the editor.

In 1876, a Lord’s Day Observance Society was formed in Brisbane with Anglican Bishop Hale as its president. This was modelled on the society formed in England in 1831. They were concerned with such developments as the Government commencing train services on Sundays in 1865, and fifteen years later rubbing salt into the wound by discounting ticket prices on the Sabbath.

The Society fades from the news from around 1890, however the influence of churches in politics continued to be strong and influenced laws relating to Sunday activities.

The sale of alcohol

Over the years, the most common prosecution by far related to Sunday trading was for selling alcohol.

On its foundation in 1859, the colony of Queensland inherited existing New South Wales legislation which outlawed Sunday pub sessions. In 1862, the sale of alcohol was allowed from 1 to 3pm, but strangely it could not be drunk on the premises. Queensland’s 1863 law mirrored this legislation, however, police usually turned a blind eye to breaches and many pubs allowed drinking on the premises and opened for much longer. Things changed in 1884, when a crackdown commenced in Brisbane, probably at the urging of temperance groups.

The temperance movement had been growing in Australia since the 1830s with the founding of Friendly and Temperance Societies such as the Independent Order of Rechabites, the Good Templars, the Band of Hope and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, all strongly connected with nonconformist Churches.

They successfully lobbied Parliament to adopt much more stringent conditions on the sale of alcohol and granting of liquor licences in the 1885 Licensing Act. See my post “Nicholas Walpole Raven And The West End Pub with No Beer” for an interesting example of the difficulty in obtaining a licence after 1885.

Many of the colony’s parliamentary representatives were members of Churches that strongly advocated the complete abolition of alcohol, and were very receptive to the lobbying of the various temperance groups. For example, under the electoral system of the time, there were two members for South Brisbane, Simon Fraser and Henry Jordan. Simon Fraser (see my post The Three Torbrecks) was a staunch member of the Congregational Church whilst Henry Jordan was a lay preacher in the Wesleyan Church on Vulture Street.

The Sunday trading issue continued to flare up from time to time. On one Sunday in 1934, police used “a fleet of rapid motor cars” to raid all hotels from Brisbane south to the border, acting on complaints that Sunday trading was rampant. The following year, Sunday opening was still so prevalent that members of Licensed Victuallers’ Association voted to close hotels on Sundays, which was in any event illegal.

As well as no Sunday opening of pubs, they also closed at 8pm on other days, although somewhat perversely they opened at 8am. After a period of laxity, police started to strictly enforce this in 1940. In October, large numbers of Australian troops, many about to be sent to North Africa and Singapore, rioted in Brisbane’s CBD. Police were unable to control the rioting, which continued until 2am.

After long debate, the following year pub opening hours were changed to 10am to 10pm, but Sunday opening was not introduced.

Finally, the 1965 Liquor Act allowed Sunday opening of hotel lounges from 11 am to 1 pm and from 4pm to 6pm, but only more than 40 miles (64 kilometers) from the Brisbane GPO or in “designated tourist areas’, of which there was but one, Redcliffe. Exceptions were made for restaurants and dining rooms when a meal was consumed.

In 1970, there was a push to relax these rules, and teetotaler premier Bjelke-Petersen left resolution of the issue to his liberal colleague, Dr. Peter Delamothe, as it was a “city issue”

Despite opposition from some church leaders, Delamothe pushed through changes to the Act, including extending Sunday trading to Brisbane, allowing bars as well as lounges to open, and admitting women to public bars.

When a group of women arrived the West End’s Boundary Hotel in November of that year to test the law, they were refused service by the publican, Mrs. Pitt. She called the police from across the street, but they were unsure of the new law and retreated back to the Police Station. The women remained at the bar but had to ask men to buy their beers as they were refused service.

Finally in 1992, the restricted trading hours were largely removed.

Shop Opening

The New South Wales Police Act of 1838 required that the “Lord’s Day to be duly observed by all persons” and specified only a limited number of traders who could open, such as “butchers bakers fishmongers and greengrocers until the hour of ten in the forenoon”. This legislation became part of the Queensland legal framework. From time to time particular Sunday activities came to the fore. Here are a few examples.

Newspapers

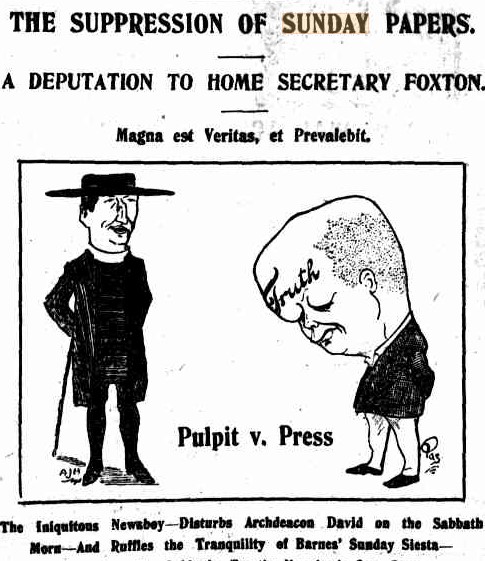

The issue of newspaper sales on Sunday flared up early in the 20th century. In March of 1901, a deputation of clergymen met with the Queensland Home Secretary Justin Foxton to complain about the issue of noisy newspaper boys early on Sunday mornings, described as “discordant squalling on Sunday mornings of a newspaper, and now two papers“.

Foxton was sympathetic. Legal advice was that specific legislation was required, and by October, a bill was before parliament. It would have made illegal the publishing, distributing, selling, circulating and disposing of newspapers on a Sunday.

It failed to progress, and in September of the following year, a group of 26 representatives of Protestant churches and associations returned to meet with Foxton. This included the Venerable Archdeacon A. E. David, who complained that Church of England services were disturbed by the sounds of newspaper boys outside, desecrating Sunday.

The Truth newspaper, whose Brisbane launch in 1900 had created the problem and was only published once a week on Sunday, featured Archdeacon David in a cartoon along with the controversial Sydney-based owner of the various Truth newspapers around Australia, John Norton.

Foxton attempted to get the bill suppressing Sunday newspapers through parliament in 1903, but the Philp Government fell and was replaced by a cross-bench coalition led by Premier Morgan which did not pursue the issue further.

Bread Sales

Responding to the demand for freshly baked on Sundays often landed bakers and their employees in court. There was a spate of prosecutions through the 1920s, based on breaches of the bakers and pastrycooks award. Not only bakers, but also carriers and shopkeepers who received bread on Sunday were fined over the years.

Bread was baked on a Sunday, but could not be transported or sold until Monday. In 1934, one baker was even fined for giving his nephew who worked for him some loaves to take home from work on a Sunday. Proponents of Sunday sales pointed out that workers’ lunch sandwiches on Monday were made with Friday’s bread.

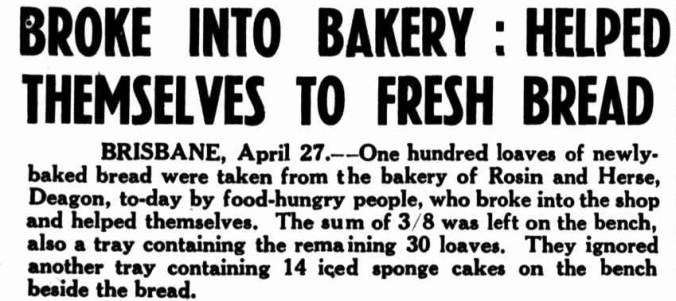

On a Sunday in 1947, hungry people broke into a bakery where bread had been baked for the next day. A queue formed and a total of 100 loaves of bread was taken, with payment left on the bench. There had been no bread for sale for 3 days due to an Anzac Day holiday.

In 1953, enterprising bakers started selling partially cooked bread rolls that allowed families to enjoy fresh bread on Sunday. From around that time, supermarkets grew in popularity, and large bakeries increasingly focused on supplying them with packaged sliced bread. Small local bakeries started to disappear.

By the 1970s, the restriction on Sunday sales of bread had been removed. This allowed the rapid growth of small “hot bread” in-store bakeries, which was a return to the old days of small local bakers. They catered to a strong demand, and long queues would form on a Sunday morning.

Other common prosecutions for Sunday trading over the years related to the sales of cigarettes, soft drinks and ice cream.

Changes in Sunday trading laws

Over time, the focus of Sunday trading moved from meeting religious obligations to the social impacts on those who were required to work on Sundays, the need for time-poor people to shop on Sundays and the adverse effect on small traders of allowing large retailers to open. By the 1980s, many types of small retail shops were classified as exempt and allowed to open on Sundays, in recognition of the desire of the public to shop in their free time. These included a wide range from food, fruit and vegetable shops and restaurants to antiques, camping equipment and sporting goods shops. In Queensland today, a complex set of rules applies.

Sunday leisure

Fishing

In 1871, a correspondent to the Brisbane Courier complained that on a Sunday there were “no fewer than 5 boats and punts well ladened with anglers anchored at the site of the proposed bridge” (see my post “The Fascinating Story of the First Victoria Bridge” ). This was “highly insulting to the feelings of those who study to observe the law and spend the Sabbath in a manner becoming to its sanctity“.

Forty years later in 1914, there were still those who were aghast at the sight of people fishing on Sunday, this time from Orleigh Park.

“On Sunday last an excellent catch of flathead was made in the Orleigh reach by some West Enders, who, if they do not break records in fishing, are credited with breaking the Sabbath by a few hypocritical wowsers living up that way, who turn up their eyes with horror when the lads do a bit of Sunday fishing.“

Cinemas

Cinemas started operation in Brisbane in the 1890s, and from around 1910, purpose built cinemas began to be constructed all over the city. They were, however, closed on Sundays. A 1935 newspaper article compared Brisbane to London and US cities, where there were no such restrictions.

“There is no hint of the gloom which hangs over an Australian Sunday, when streets are deserted in the day time and few people walk disconsolately up and down the main thoroughfares, bored to distraction.”

During World War 2, yielding to pressure from the armed services, Sunday screenings were permitted from 1942. After the war, this ceased. Sunday cinema had to wait until 1968, when the Brisbane City Council allowed opening from 1pm until 10.30pm. Some cinemas had been opening illegally before then.

Alderman Jones said his administration had considered several factors in drafting the amendments. Lack of enough to do on Sundays, it was claimed, led to large numbers of youths and girls who drifted aimlessly through the city on Sundays.

Representatives of the Roman Catholic and Anglican churches had no objections, but the Queensland Council of Churches spokesman, the Reverend R. E. Pashen, commented that “Sunday is the Lord’s Day, and it is a shameful commentary on the community’s outlook that it should be held in such low esteem that yet another part of it is to be whittled away”

Sport

Organised sport had long been forbidden by local government regulation, and this aspect of observance of the Sabbath turned nasty in 1921. The year before, a group of tennis players had requested permission from the South Brisbane City Council to use the Musgrave Park courts on Sundays, but had been refused.

The Council continued to wrestle with the issue through 1921, with at times acrimonious debate. Alderman Woodland in particular was disgusted at the Sabbath breaking that was occurring.

“The youths and men who congregated in the parks on Sunday were only the riff-raff and the rabble, men without backbone”

Twenty three religious bodies had written urging councillors to ban all sport in parks on Sunday. Meanwhile, a deal had been struck with the South Brisbane Cricket Club for the use of Davies Park (see my post The Davies Park Story) and a number of ovals were bring prepared with soil that had been brought in and grass planted.

It appears that some informal groups had been playing on the new pitches on Sunday, and the Saturday night after, extensive damage was done with the surface of two practice wickets destroyed. Blame was placed on “puritan brigands” but the culprits were never identified. There was talk of a vigilante group to guard the pitches against further attacks.

As it transpired, the council passed a by-law a few days later with the following wording.

“No person shall in any part of the city parks or reserve play or take part in any game of football, quoits, bowls, hockey, cricket, or any other sports or games on Sundays.”

After World War 2, local councils increasingly turned a blind eye to Sunday sporting activities. Paid admission to sporting activities was not allowed, but many organisations got around this by asking for “donations” at the gate.

The ban on Sunday sport sometimes caused great disappointment. On a Saturday in December of 1950, a large crowd patiently waited outside the Woolloongabba Cricket Ground for the gates to open on the second day of the first test match against England. Play was cancelled due to a wet wicket and couldn’t be resumed on Sunday due to the prohibition. There were few people waiting when the gates opened on Monday,

There were cracks in the wall. The Australian Tennis Championships, now known as the Australian Open, took place at Milton, Brisbane, in 1956. Sunday matches were held after rain delayed play. The Reverend R. Pashen complained that “the Christian Sunday is being sabotaged again in the interests of commercialisation”.

In 1962, restrictions on Sunday sport in Brisbane were removed.

The seriousness attached to the observance of the Sabbath in times gone by seems strange to most Australians now, although it still remains an important tenet of faith to some.

© P. Granville 2025