This is the third of a series of posts about local families whose businesses in South Brisbane and West End grew to become household names before disappearing. I previously looked at tinsmith Thomas Cole and the Queensland Can Company and Thomas Dixon and his tannery and boot factory. This post looks at South Brisbane soft drink manufacturer, Thomas Tristram.

Joseph Tristram

In 1823, Thomas Tristram’s father Joseph was born in Macclesfield, Chester. At the age of 16, Joseph enrolled in the 12th Regiment of Foot, one of the oldest regiments in the British Army, founded by the Duke of Norfolk in 1685. He served a total of 28 years in the 1st Battalion, never rising above the rank of private.

After six and a half years stationed in Mauritius, Joseph returned with his battalion to Newry, County Down, in what is now Northern Ireland. There in around 1853, a son Thomas Tristram was born to his wife Mary Elizabeth nee Smith. Details of Joseph and Elizabeth’s marriage remain elusive.

It was to be a short posting in Newry, as in 1854 the first Battalion was sent to Australia, where it remained until 1867 performing garrison duties. These included defence of the colonies, surveying, exploration, policing, and supervision of convicts. The Battalion also spent time in New Zealand and took part in the New Zealand Wars.

The Melbourne Argus reported the arrival of the Empress Eugenie carrying the third contingent of the Battalion in November of 1854, having departed from Cork in late July. Amongst the 167 rank and file soldiers, 25 women and 34 children were Joseph, Elizabeth and toddler Thomas Tristram.

Thomas Tristram’s early years

Thomas lived in various cities during his childhood, as Joseph was moved around between the Australian colonies. Along with other army children, he would have attended schools in the barracks with teachers employed by the army.

A small detachment of 28 men of the Battalion, including Private Tristram, along with 3 women and nine children, was sent to Brisbane early in 1861 . There they performed guard duty at the new Queensland Government House. In 1866, they were involved in quelling the Brisbane Bread Riots. Later that year, a detachment, including Joseph, was sent to New Zealand to join the remainder of the battalion, where they participated in the Second Taranaki War.

In May of 1867, the 1st Battalion left New Zealand and returned to England. Joseph was discharged before they left and went back to Brisbane, where his family had probably remained. His 28 years of service entitled him to a pension of 13 1/4 pence a day.

For a period of time in the 1870s, Joseph held the licence for the Wheat Sheaf Hotel on Logan Road in the vicinity of Holland Park, but otherwise there is little record of him. Elizabeth died in 1886, and Joseph in 1890.

Soft drinks

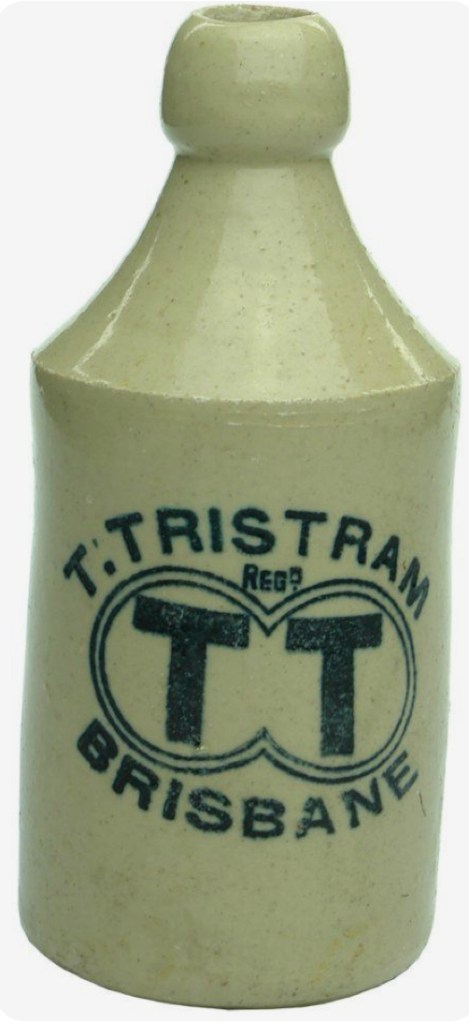

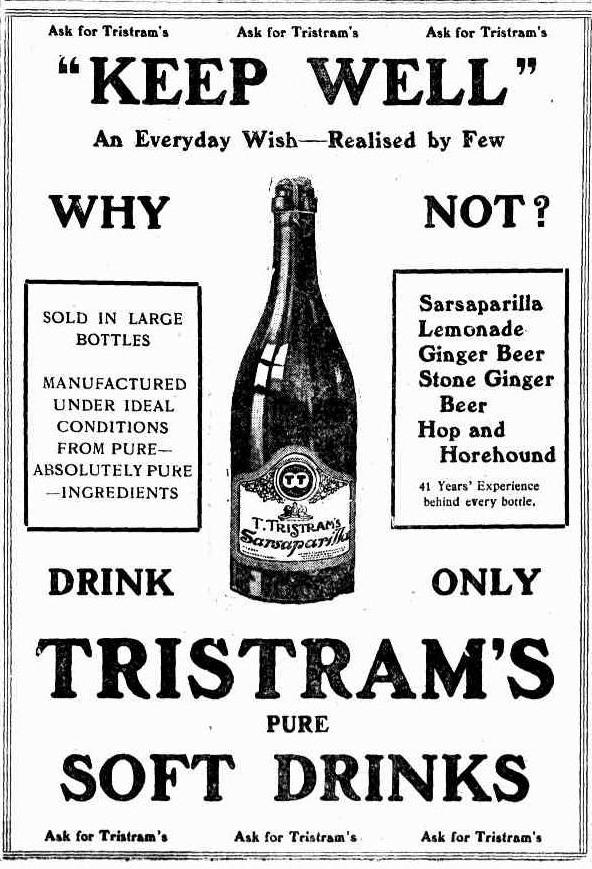

Soft drinks, or non-alcoholic effervescent beverages, produced at the time were of two types. Ginger beer was brewed similarly to beer with a natural effervescence. It contained a small amount of alcohol. Herbal beers made from, for example, dandelion flowers were also popular.

Soda water, also known as aerated water, was made by forcing carbon dioxide through water in a process invented by Joseph Priestley in 1767, as it still is today. Fruit flavours and sweeteners were commonly added.

In the early days of free European settlement of Brisbane, soda water was shipped in barrels from Sydney, although there were some local producers from an early date.

Owen Gardner

At some stage in the 1860s, an adolescent Thomas started working for Owen Gardner. Gardner had arrived in Brisbane in 1851 as a young man. According to one obituary, he made his money on the Victorian gold fields, but another says he was unsuccessful in Victoria and became wealthy through timber-getting in the Maroochy district.

In any event, in 1859 Gardner purchased an aerated water and cordial business located in William Street, near the location of the former Department of Primary Industries building at number 95. This factory had previously been owned by Kent and Drew and was established by Fisher and Gregory in 1853.

A falling out

According to Thomas Tristram’s affidavit in an 1885 court case1, in 1874 he went into business for himself, brewing ginger and herbal beer from the back of his Hope Street home. In 1876, he agreed to a proposal from Owen Gardner to amalgamate their businesses. Gardner built and equipped a factory directly opposite Tristram’s home in Hope Street. Tristram managed the factory without being paid a salary, but received half of the profit from the sale of the ginger beer manufactured by him. He managed all of the accounts of the South Brisbane factory, keeping the ginger beer transactions separate.

The arrangement continued until 1885 when things turned sour. The trigger to the dispute was probably Tristram entering into another partnership with Henry Thomas House.

Unfortunately the partnership between Gardner and Tristram had never been formalised, according to Tristram because Gardiner did not want to incite the jealousy of his other employees. Gardner, in his affidavit, asserted that Tristram had always been his employee, and that there were irregularities in the profits that had been passed on to him by Tristram. For unknown reasons, Tristram had burnt what he referred to as his private memoranda notebooks that Gardner believed were the cash records.

In the civil action Gardner v Tristram, Judge Harding determined that Tristram should pay Gardner the substantial sum of £1,000, however records of the reasoning behind the decision have not survived.

Emily Freeman

In 1865, Emily Constance Freeman was born in the parish of Hedenham, Norfolk, to mother Sarah and father Frederick, who were farmers.

Emily emigrated to Brisbane in 1884, travelling on the Merkara. Thomas Tristram and Emily Freeman married later that year, just 5 months after her arrival.

Tristram’s is born

The partnership with Henry House came to an end in 1886, and Thomas and Emily founded a new firm, T. Tristrams.

The enterprise grew successfully until the devastating 1893 floods which hit Hope Street particularly badly, setting things back significantly.

Emily’s 1952 obituary recounts how Thomas’s health declined from this time and she took over running the business, often working until 11 o’clock at night. She also delivered drinks, carried in baskets from door to door. Thomas died in 1909 from meningitis.

By this time, Emily’s two sons and 3 daughters were old enough to help run the business. Her son Eric eventually took over running the company with his mother.

Changes in technology

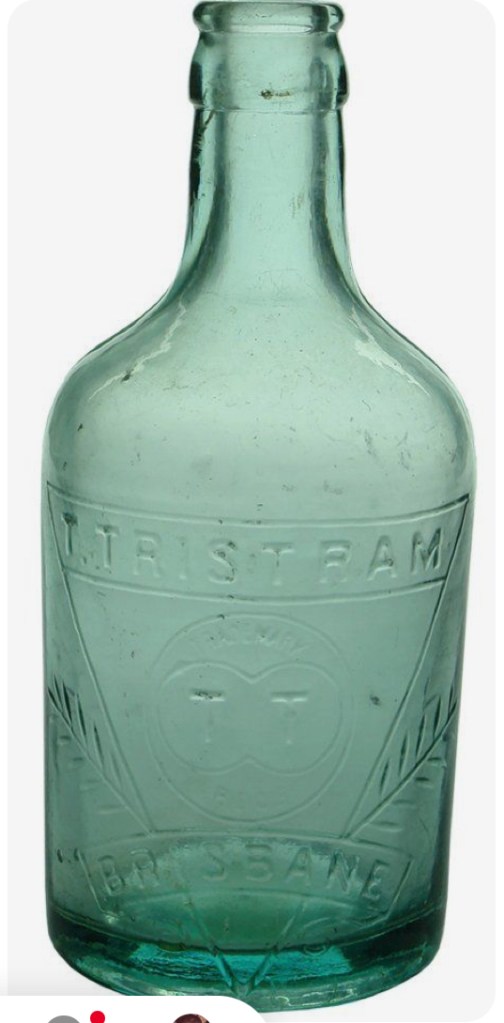

Early in the 20th century the stoneware bottles gave way to glass.

Bottles were sealed by a cork wired down to prevent it popping out. Hand wiring corks required strength and skill and Tristram’s frequently advertised for young women to do this work.

In 1916, Tristram’s introduced crown seals, replacing the labour intensive wired down cork seal. They had been invented in the USA 24 years previously but weren’t introduced to Australia by the American company holding the patent until 1902.

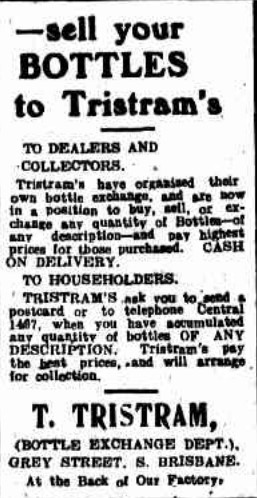

The supply of bottles was a problem, and in 1917 Tristram’s initiated a collection scheme of their own, rather than rely on third party “bottle-ohs” to collect bottles door to door.

The Grey Street factory

In 1918, Tristram’s built a new factory on land at the rear of the Hope Street property, facing Grey Street.

There had been Council plans to widen Grey Street since 1918. It and surrounding streets had been surveyed in 1842 at a width thought sufficient for the village of South Brisbane, but by 1918 this was causing ongoing congestion problems due to the heavy traffic across Brisbane’s then only cross river bridge.

Tristram’s had sought an extension of time to complete the extensive building modifications required, and work didn’t commence until 1933, a year after the Grey Street Bridge had been completed. The front of the building was cut back by 14 feet (4.2m) and the side facing Fish Lane by eleven feet (3.4m) .

Today a remnant of the factory with the 1933 facade still stands on Grey Street, with a distinctive asymmetric roof line resulting from the demolition of the front of the building.

A new factory

The 1920s saw an increase in the consumption of soft drinks. A 1929 newspaper article, commented that “a few years back only certain shops stocked soft drinks, while to-day practically every suburban shop, be it general or specialised store, has its well-appointed ice-chest, and rows of bottles containing all varieties of soft drinks, from the homely lemonade to the latest fruit drink.”

Responding to the increase in demand and reduction in size of the truncated Grey Street factory, in 1929 Tristrams’ decided to build a new factory on Boundary Street, officially in South Brisbane, but often thought of as West End.

With a permanent supply of fresh water from a nearby swamp, it had for many years been the location of a Chinese market garden. In 1914, the company founded by Thomas Tristram’s partner and later competitor, Owen Gardner and Sons, built a new soft drink factory on the site. Gardiner had died in 1888 leaving the business in the hands of his sons.

The new building was designed by architect Arnold Henry Conrad ,who did much to popularize the ‘Spanish Mission’ style in Brisbane. The reported estimated cost was £25,000 and the contract for construction was let to Walter Taylor of Graceville2.

Tristram’s imported state of the art filtering equipment for its new factory.

Tristram’s kept up with the times, and in 1938 installed the latest Meyer Dunmore bottle cleaning machine.

Community involvement

As well as providing employment, Tristram’s allowed the use of its front garden for fund raising events for local charities such as the Queensland Bush Children’s Health Scheme which held garden parties on the lawn in the 1930s.

Tristram’s supported Queensland soccer competitions in Queensland for many years. The Tristram’s Shield, inaugurated by Eric Tristram, was the major knockout cup competition for the Brisbane region from 1921 to 1958.

The Kirk’s dispute

Owen Gardener and Sons had an employee by the name of Thomas Kirkpatrick who, in 1924, had developed a distinctive dry ginger beer recipe which he kept secret. The company marketed it under the name “Kirk’s”.

In 1935, Kirkpatrick left Owen Gardner and Sons after the company became bankrupt. Kirkpatrick, who believed he had personal rights to the recipe and the brand name, sold them to Tristram’s, who began producing his ginger beer using the Kirks brand.

The new owner of Owen Gardner and sons, Robert Sweeney, sued Tristrams, seeking £1,000 claiming that these rights belonged to the Gardner business he had purchased. He was successful, and Tristram’s was ordered to stop using the Kirks brand and pay Sweeney a minimal £25.

A household name

Similarly to many other enterprises, Tristram’s encountered difficulties with material supplies in the immediate post war years. In 1946, a shortage of bottles held up soft drink production as Tristram’s and other drink manufacturers were reliant on the return of used bottles which remained the property of the manufacturer. Mr. A. Davidson, then manager of Tristram’s, estimated that there were more than 3,600,000 bottles being “hoarded” in Brisbane. “Bottle-ohs” plied the streets buying empty bottles for around sixpence a dozen, sorted them, and on sold them to the various drink manufacturers.

Along with other household names such as Peters “The Health Food of a Nation” ice cream, Bex, and Billy Tea, a “Say Tristram’s Please” sign was usually visible at every corner store .

Tristram’s unblemished reputation for hygiene suffered a blow in 1951, when 2 cockroaches were found in a bottle of their soft drink. In the subsequent prosecution, company representatives testified as to how they produced 10 million bottles of drink a year, using a modern £15,000 bottle washing machine, and filling and capping plant worth £30,000. The cockroaches were thought to have entered the bottle in a 10-foot (3 metre) stretch along a conveyor belt, where a human spotter looked for dirt in the bottles. The two managers were fined a token £1 each.

The end of Tristram’s

A major change to the soft drink market had occurred as a result of World War Two. In 1941, the President of the Coca‑Cola Company, R. W. Woodruff, decided to make Coca‑Cola available to all US service personnel, wherever they were serving.

Whilst Coca-Cola had been available in Australia since the early 1900s, its sales had been very low. With Brisbane being the main US military location in Australia, in 1942 a factory was established on Balaclava Street, Woolloongabba. Sales soared, with the factory often operating 24 hours a day to meet the demand of the nearly 80,000 Americans stationed in Brisbane at the peak of the war.

The taste for Coca-Cola soon spread to locals. For example, a 1942 article about young women volunteering as drivers for the US Army commented that “Most of the girls have adopted American customs. They chew gum and drink coca cola.”

From 1950, the Coca‑Cola Company progressively granted franchises at 30 locations across Australia. In 1951, Pepsi entered the Australian market. Local manufacturers responded to the new competition by amalgamating to gain economies of scale. In 1959, Helidon Spa Water Company and Owen Gardner & Sons merged to form Helidon Gardner Pty Ltd, using the brand name “kirk’s”.

Tristram’s decided not to accept an offer to participate in the merger of its competitors.

In 1963, British Tobacco Company, later AMTIL, began expanding into food and beverages. In 1964 it purchased Helidon Gardner, which also held a Pepsi franchise. Helidon-Gardner held over 30% of the Brisbane market with the main competitors being Coca-Cola, Tristram’s and Golden Circle.

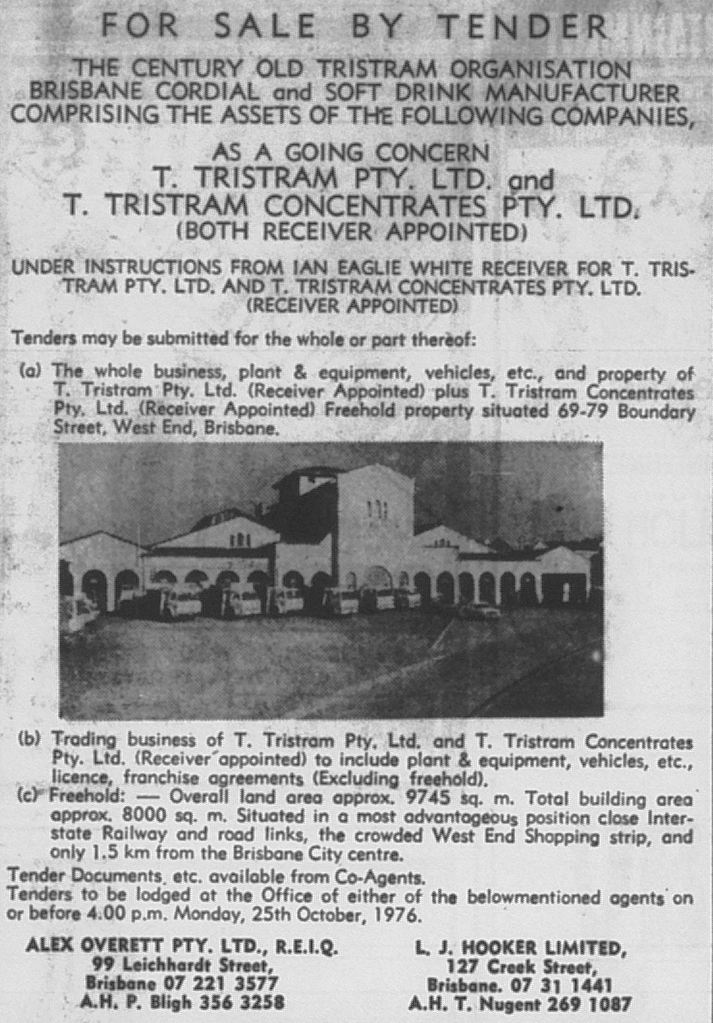

By 1976, the struggle for profitability with increasingly large competitors was lost, and Tristram’s was placed into the hands of receivers. Cadbury-Schweppes purchased the trading business, and the Boundary Street factory was sold in 1979.

In 1970, the Tristram family established Trisco Foods Pty Ltd, now a highly successful award winning producer of food related products.

From factory to shopping centre

After heavy modification, in the early 1980s the building reopened as the West End Markets with the anchor tenant being the cut price retailer Jack the Slasher.

In 2001, Heritage Pacific acquired the property for redevelopment as a mixed use major retail facility and apartments. The centre was subsequently relaunched as the Soda Factory, run by SCA Property Group, who purchased it in 2014 for $32 million. In June of 2024, the property’s sale to a private investor for $42M was announced.

References

- Queensland State Archives, Series ID S5687, Writs Civil – Supreme Court, Brisbane, Item 684.

- The A&B Journal of Queensland, March 10, 1930 Page 13.

Most references appear in the text as hotlinks.

© P. Granville 2024

Hi Paul – great article about Tristrams. Thankyou!

I owe you a copy of the house history that I had done for our home at 24 Dauphin Terrace. I will figure out how to get that copied and drop to you. I know you live on Dornoch Tce, but which number? I can drop in mailbox if you aren’t around. I am not sure when I will get it done but it’s on my list!

Enjoy this beautiful weather.

Jacqui

Sent from Outlook for iOShttps://aka.ms/o0ukef

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Jacqui

Thanks for your comment. We’re at no 132.

LikeLike

Paul, as usual, a great piece of work.

Bill

Dr William J Metcalf

Adjunct Lecturer, Griffith University,

Honorary Associate Professor, University of Queensland,

Brisbane, Australia

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Bill

LikeLike