This is one of a series of posts about local family businesses in South Brisbane and West End that became large enterprises employing many local residents, only to cease operations or lose their identity through a take over. Other posts include James Cole and the West End Can Factory and Say Tristram’s Please!.

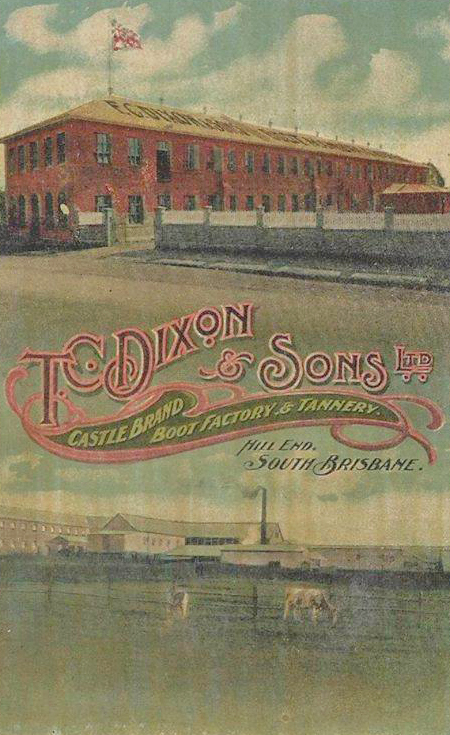

This post looks at tanner and shoe maker T. C. Dixon and Sons and its battles over 100 years with flood, fire, and imported footwear.

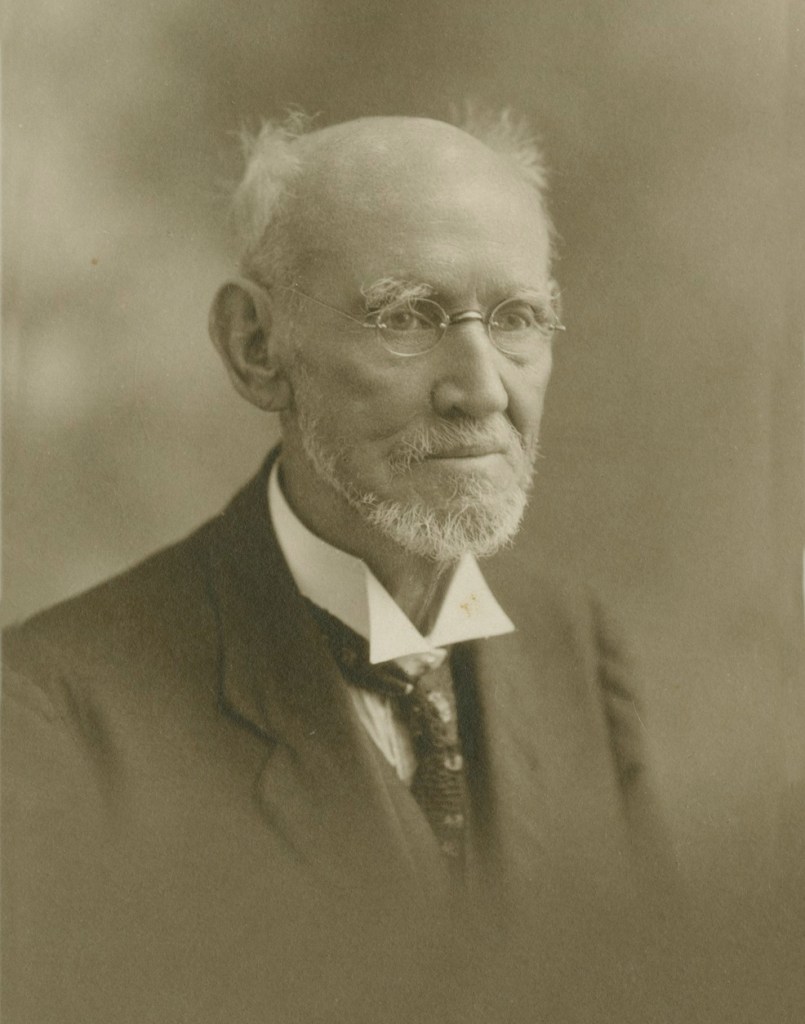

Thomas Dixon

Thomas Dixon was born in 1845 at Bradford in Yorkshire, England. His father, also Thomas, was a prosperous ironmonger.

Along with his elder brother, Joseph Chapman Dixon, he attended the Quaker school at Ackworth, in West Yorkshire.

In 1866, Thomas, by then trained as a tanner, emigrated to New South Wales where he established a tannery in Moruya1.

The move to Brisbane

Thomas’ older brother Joseph, a grocer, had arrived in Australia in 1864. In 1869, he was one of a group Quakers who established a sugar farm and mill on the Mooloolah River. He left the sugar industry in 1895 after suffering large financial losses, and then ran a shoe shop in Gympie for 11 years in conjunction with Thomas. He lived out the rest of his life building up an orchard in Flaxton.

On the advice of Joseph regarding the opportunities in Queensland, Thomas moved to Brisbane sometime around 1873 and appears to have established a tannery at Hill End on leased land. In his memoirs he describes how he “built a 2 story Factory 50 x 20 long, facing Montague Rd. & after sent it down the paddock on a roller.” 3

A tannery requires large amounts of water, and the location he chose was next to an extensive permanent waterhole known as Kurilpa Swamp, which was also being used by market gardeners in the area. See my post Kurilpa – Water, Water Everywhere for more on this.

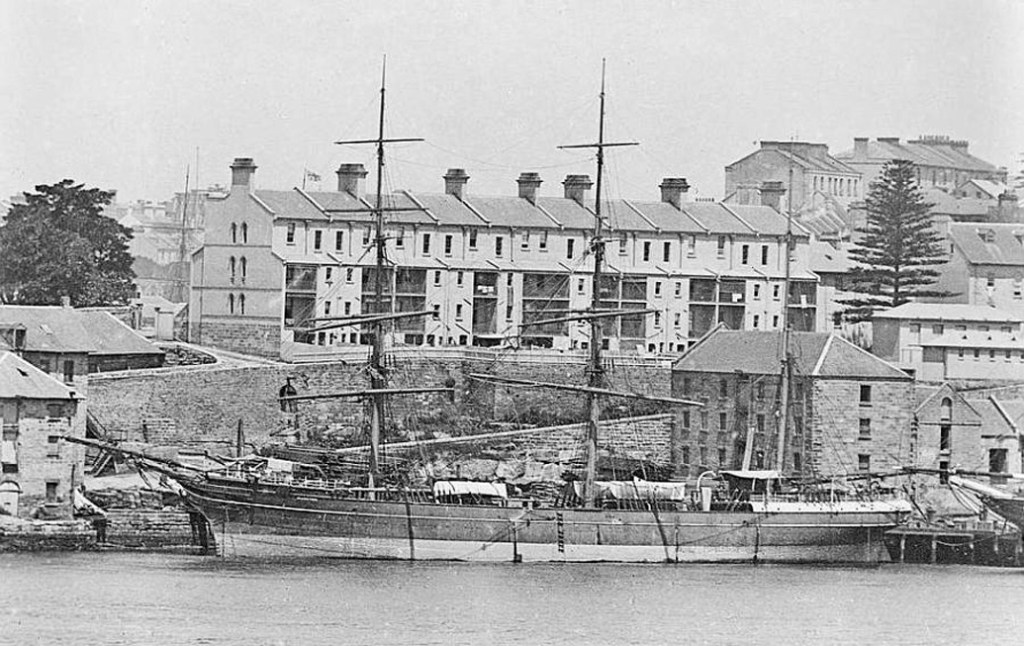

Dixon travelled from Melbourne to Liverpool in 1874 and in early 1875 returned to Australia, this time arriving in Brisbane on board the Francesco Calderon. The trip home was possibly to obtain financial assistance from his family.

Towards the end of that year, Dixon purchased 5 acres of land at Hill End for his tannery, paying £500. The land had been part of Coombe’s Farm, as described in my post The Origins of Orleigh Park . Thomas dug his own tanning pits and would row a whaleboat down river to Bulimba to purchase hides and return with the incoming tide2.

Elizabeth Clacher

The Clacher family were cotters, or peasant farmers, in Gargunnock, near Stirling in Scotland. In 1853, being threatened with eviction, the family comprising Thomas and Ellen along with their four children under the age of 5, emigrated to Australia under the auspices of the Highland and Islands Emigration Society. This charitable organisation had been established the year before. As was all too common, the youngest child Helen, just 13 months old, was one of the four children who died on the voyage.

The Clachers settled in Ernest Street, South Brisbane, where they had another 7 children. In 1877, Elizabeth, who was one year old when the family arrived 24 years earlier, married Thomas Dixon. The next year their first child Ellen was born. Ellen died within a few months, but over the next 15 years Elizabeth gave birth to 7 more children, all but one reaching adulthood.

Ups and downs

In 1878, Dixon established a store in Stanley Street and a boot making factory in Russell Street, South Brisbane, making use of the leather produced at Hill End. He used the brand name TCD, which were his initials. He also built a second tannery building at Hill End.

In 1880, Dixon relocated the boot factory to Hill End and by 1882 had moved his store across the river to George Street. The family lived close to the factory in “Myora” on Montague Road. At a little after one o’clock on a Friday morning in October of 1885, Elizabeth Dixon was awakened by her daughter crying, went to her bedroom, and saw the factory buildings on fire through the window.

The sound of the South Brisbane fire bell after she raised the alarm woke many residents “and rang so persistently that many persons were roused from their beds and, guided by the reflection, rendezvoused at the Victoria Bridge. From that point of observation the fire was seen to be extensive, but too far away for any but the most curious of sightseers and the more zealous of the City Fire Brigade men.”

Nothing could be done to halt the spread of the fire, as the area was outside the range of reticulated water. Five buildings were destroyed, including the tannery and boot factory, along with all the machinery they contained and a large stock of boots, with a substantial loss of around £5,000. Dixon replaced the destroyed buildings and also by 1887 had closed his George Street shop. However, trouble was afoot.

As described in my post The Origins of Orleigh Park, from 1884 the surrounding farm land was subdivided into residential blocks, and house construction soon began in earnest. The local council, at that time the Woolloongabba Divisional Board, received so many complaints about the smell, that in 1886 they wrote to Dixon giving him 6 months to remove the tannery, in accordance with their bylaws.

Dixon avoided this outcome in some unknown manner, only to have the 1893 flood destroy £1,500 worth of his stock and sweep away the tannery shed at the rear of the property.

Not long after the flood, Dixon replaced the destroyed tannery.

Around this time, Thomas purchased a large holding of land in the Blackall Range district where he developed a dairy farm. The property overlapped the site of the future town of Maleny, and as it developed, he donated land for the butter factory, primary school, and School of Arts. In 1912, the family sold the remaining land, subdivided into 18 farms and 40 town allotments.

Employee activities

The company and employees organised recreational activities. For example, for decades, the T. C. Dixon team competed in various cricket competitions run by groups such as the Warehouse Cricket Association. As was common at the time, the company hosted an annual picnic for employees. In 1899, around 200 workers and their families travelled to Redcliffe on the Grazier. After a “sumptuous repast” at a local hotel, sports events were held before afternoon tea and the trip home.

Dixon also built a number of worker’s cottages in the nearby streets to house his workers2.

Expansion

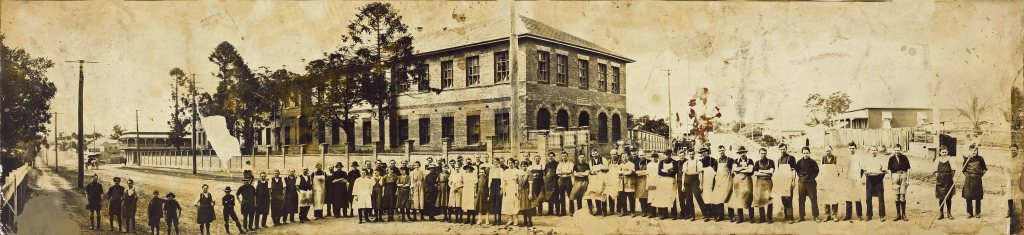

In 1907, needing more factory space, Dixon engaged well known architect Richard Gaily to design a new factory on land which Dixon had purchased diagonally across the street from the existing factory and tannery. Other surviving works of Gailey include Moorlands at Toowong, the Baptist Tabernacle on Spring Hill, Tara House and the Brisbane Girls Grammar School.

The new factory building was opened in April of 1908, with around 200 guests, including employees and their families and friends, attending a celebration. During the evening, Thomas announced that his sons were ready to take on bigger roles, and he changed the name of the company to T. C. Dixon and Sons. After the formal part of the evening, dancing continued almost to midnight.

Less than a year later, in 1909, there was yet another disastrous fire, this time in the two storey wooden factory built after the 1885 disaster. This blaze was thought to be caused by an employee dropping a match after lighting his pipe while leaving the factory at the end of the day.

The Dixon family and many employees who lived nearby rushed to the scene. Despite their efforts and then those of the South Brisbane Fire Brigade, the fire totally destroyed the building and its machinery. The employees on the scene saved what they could. “Bales of singed and saturated kid and leather were snatched from under the firemen’s hose, smelling horribly”

A new brick tannery building was built soon after, and it remains on the site today.

Just 9 months later, Thomas Dixon died, aged 63. Elizabeth passed away 9 years later, in 1918.

The next generation

After Thomas’ death, his son Ernest ran the factory, while William took over management of the tannery. With the depressed economic conditions of the 1920s, Australian shoe manufacture went into decline and imports increased. In 1931, Dixon’s placed a feature in the Daily Standard stressing their purchases from local companies, and asking for local support in return to counter this threat to their business.

“We want that loyalty in Queensland” said Mr. Dixon. “Queenslanders could show the same spirit , and there would be greater industrial progress and expansion”.

Advertisements from the 1930’s for Dixon’s Castle and Pleasurefit brands.

A Tariff Board report noted that British wages in the industry were around 50% of those in Australia, and as a result imported British shoes were significantly cheaper. The Commonwealth Government increased import tariffs, which by 1932 reached 45% for British footwear and 65% for others. This reduced imports to a fraction of their previous levels, and by 1935 local manufacturers were supplying an estimated 99% of the market.

In 1933, Dixon’s were turning out about 2,500 pairs per week, with the capability of producing 8,000 pairs. Their staff totaled 200 in the factory and over 100 in the tannery. By 1939, production had returned to the levels of the early 1920s at around 4,500 pairs a week.

During the Second World War, the company received large orders for military footwear, and by the end of 1940 had already manufactured 80,000 pairs of army boots. In 1944, they won a contract to manufacture shoes to be provided to discharged soldiers, to go with the suit also provided to every soldier.

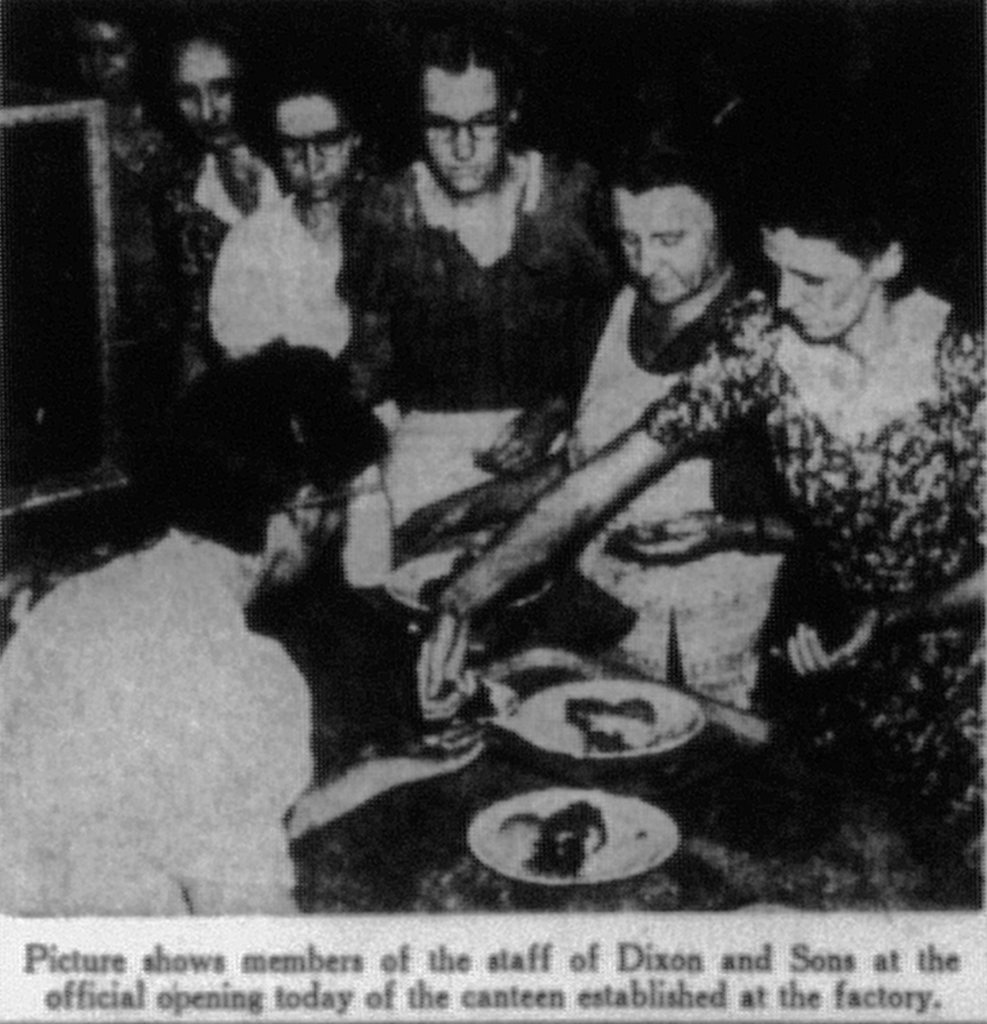

In 1945, Dixon’s opened a staff canteen, providing subsidised meals for the then 180 employees at Montague Road. It provided “a good meal consisting of an entree, a choice of two salads, sweets, and tea or soft drink“.

The post war years with rationing and price controls were at times difficult. Materials were often scarce, threatening production and employment.

In 1952, the State Price Commissioner refused to grant an increase in leather prices to tanners resulting in a critical shortage, as manufacturers reduced production and sold their leather outside the State. Things came to a head when shoe manufacturers ceased operation. Along with other Brisbane factories, Dixon’s laid off all 205 of their employees before the commissioner finally agreed to a price increase.

Also in 1952, there was yet another factory fire, thought to be caused by spontaneous combustion, that destroyed some £2,000 worth of imported linings and wooden shanks.

Having been a source of local employment for so long, Dixon’s had some staff members who had spent their entire working lives there. In 1954, the Telegraph newspaper featured two of these in a special footwear feature.

Rachel Anderson was photographed taking wrinkles out of newly made shoes using an oxygen flame. She had started in 1912 in the socking section where insoles were fitted. Storeman Norman Hall had at the time completed 50 years with Dixon’s having commenced as an apprentice in the machine shop.

Like many employees, Norman lived nearby in Mitchell street, West End. After residing for many years in Montague Road Rachel moved to Toowong, and became one of the many Dixon’s employees who travelled to work on the ferry.

The demise of Dixon’s

By 1970 the winds of change were blowing and the tannery was closed. In 1973, the company relocated its shoe manufacturing to Wacol where they employed 561 staff. The beginning of the end occurred just one year later, when two of the three Wacol factories were closed following a reduction in import tariffs2.

The factory manager, Mr. Keogh, stated that while productivity was very high with over 11 shoes a day being produced per worker, the hourly pay rate of $3 was far in excess of 28c an hour in Taiwan and 72c in Brazil, which were the chief sources of imported shoes.2 The remaining factory closed in 1980.

New lives for Dixon’s buildings

The tannery property passed through several hands, and since 1992 has been occupied by Douglas Partners, a geotechnics, environment and groundwater service and analysis company.

The factory was sold to K D Morris, and in 1975 purchased by the State Government for use as a storage facility. In 1991, after refurbishment, it became the home of the Queensland Ballet, the Queensland Philharmonic Orchestra and the Queensland Dance School of Excellence. In 2000 the building became dedicated to dance. A major redevelopment was completed in 2023, and the building is now known as the Thomas Dixon Centre.

References

- From boots to ballet shoes : the Thomas Dixon Centre celebrating 100 years in 2008 England, Marilyn.; Queensland. Department of Public Works. Brisbane, Qld. : Public Works; 2008

- Courier-Mail September 27, 1974 page 2.

- Dixon’s Tannery (former) Brisbane City Council Heritage Citation.

- Thomas Dixon Centre 601624 Queensland Government Heritage Register

Most references appear as hot links through the text.

© P. Granville 2024

Well done Paul. I look forward to reading all your interesting historical articles which all appear to be well researched. Keep up the good work and I look forward to your next blog on local history.

Regards, Brendan Palmer

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Brendan

LikeLike