While researching the early days of European settlement in South Brisbane, I came across numerous newspaper references to Mary Anne Williams. She was often in trouble with the police and became quite well known in the small community. Her story seemed poignant, and I decided to find out what I could about Mary. But first let’s have a look at the South Brisbane she lived in.

Before free European settlement

In 1824. Governor Brisbane established a settlement in the Moreton Bay area for reoffending convicts, and after a false start at Redcliffe, it was moved to where the City of Brisbane now stands.

The south side of the river opposite the penal colony was largely what would be described now as wetlands. Extensive marshes were drained by a creek that flowed into the river near the location today of Southbank lagoon. This was a busy crossing area where large groups of people would swim across the river together or use communal canoes. On the southside, a pathway led to a habitual camping area along the ridge near today’s Vulture Street and on to the Woolloongabba ceremonial area and the western districts. Behind the swamps was a hunting area known as Kurilpa, the place of the fawn-footed mosaic-tailed rat, a native Australian rodent.

The South Brisbane Mary knew

By 1839, the decision had been made to close down the convict station and most convicts were taken to other locations, leaving only those thought needed to provide labour for the settlement.

By this time, squatters had moved down from the Darling Downs and had settled the upper reaches of the Brisbane and Logan Rivers. While free settlers were not allowed within 50 miles (80km) of the Moreton Bay convict station, with the Governor’s permission ships could call at Moreton Bay and occasionally loads of wool were dispatched from the fledgling port at South Brisbane.

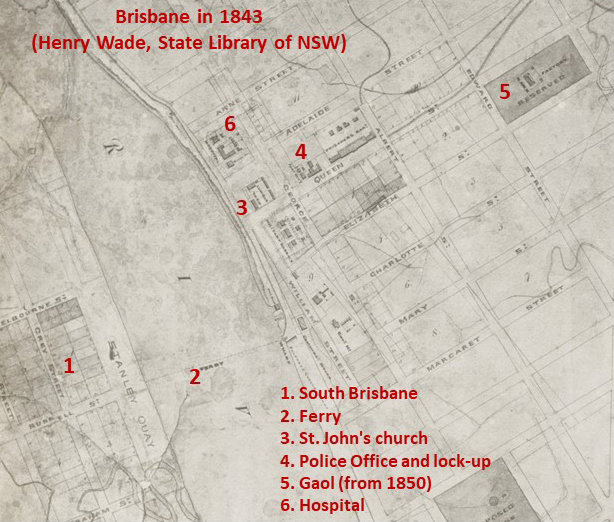

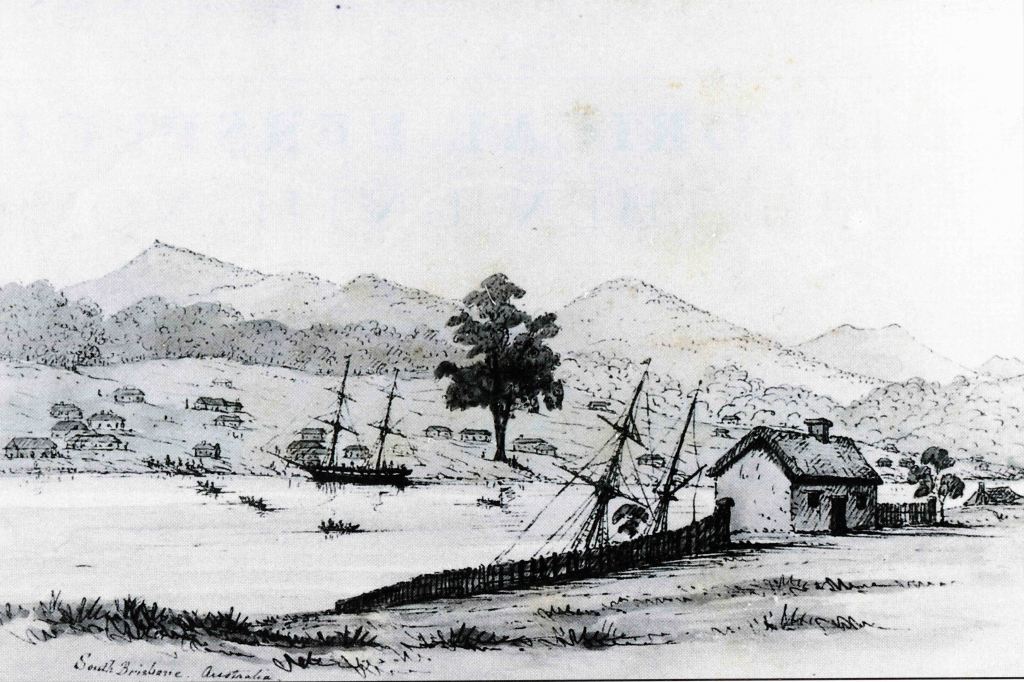

In 1842, Moreton Bay was declared open to free European settlement and squatters’ men began arriving regularly at South Brisbane with bullock teams hauling bales of wool. The first sales of land on both sides of the river were held in Sydney in that year, with complaints about some of the South Brisbane lots being on swampy land, overrun with water at high tide.

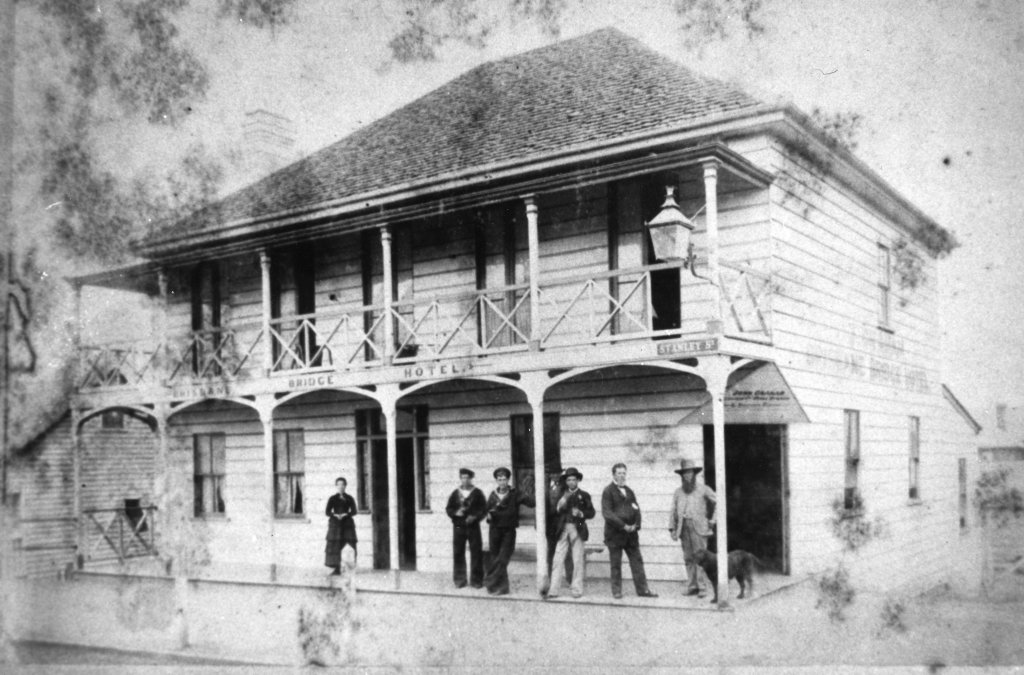

The commandant insisted that the squatters and their men stayed on the south side of the river to separate them from the remaining convicts on the north side. The sale of alcohol was banned, but it wasn’t long before sly grog began to be sold from the few shops established near the southside wharves. The ban was lifted in 1843, and from then the number of hotels increased as shipping and commerce grew.

The German explorer Ludwig Leichhardt was clearly describing the south side of the river in his comment in a letter written in 1844.

“Brisbane town, where the squatters meet at shearing time because they bring their wool there for shipment, is the recognised place for drinking, whoring and folly by night”.

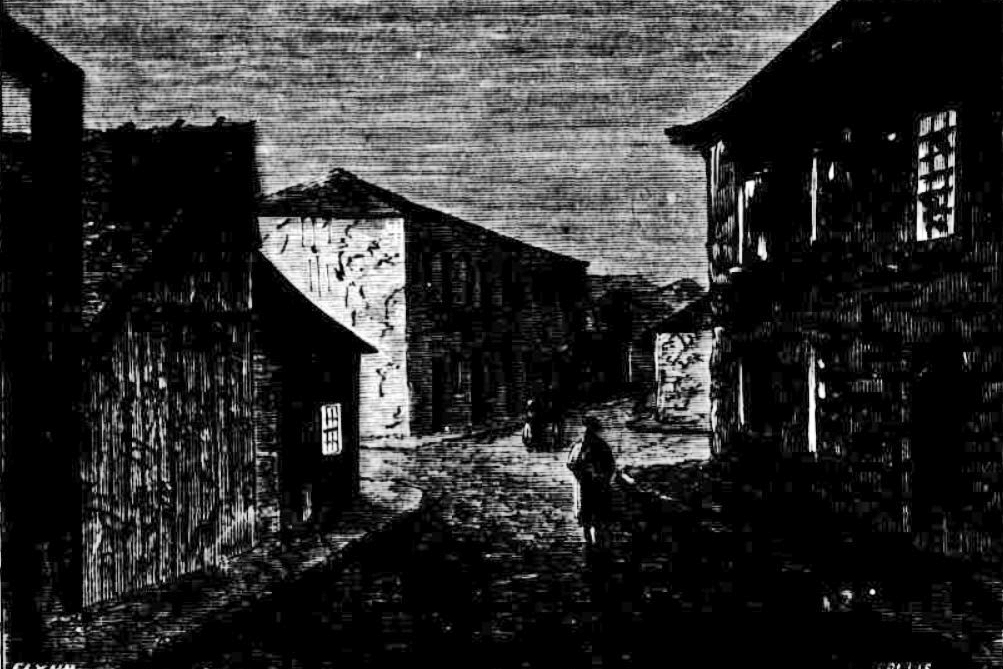

John Sweatman sailed on H.M.S. Bramble on its journeys surveying Torres Strait. The ship called into Moreton Bay in 1846. He wrote in his journal “South Brisbane I did not see much of, it is much more scattered and ill built and altogether “lower” than North Brisbane”.

Another writer recalled his arrival in South Brisbane in the 1840s.

“Passing up the road leading from the water side, in the direction of the accommodation house, we were at once in the midst, pell mell, of bullock bows and yokes wielded and hurled in fearful proximity to our persons. Yells of fiendish blasphemy were uttered on every side, whilst a woman, with her front teeth knocked out from the blow of a yoke, stood shrieking for help in the midst of this rum maddened throng. The Chief Constable, poor old White, in vain assayed to stop the murderous affray, assisted by his meagre staff of convict constables; and it was not until the military guard from the barracks reached the spot that the riot could be suppressed. These matters were far from infrequent occurrences.”

This the South Brisbane that Mary knew.

Mary’s early life

It’s been difficult researching Mary’s origins, as records are scant and contradictory. It’s likely that she was born in Dublin in about 1820 and arrived in Sydney as a child in 1825 on board the convict ship Minstrel. The Minstrel passed through the heads into Port Jackson on the 22nd of August after a voyage from London lasting almost 5 months. On board were 121 male convicts and a detachment of the 57th Regiment. The newspaper report of the arrival doesn’t mention free passengers, but a handful arrived on board most convict transport ships in this period.

Mary’s 1844 marriage record from Brisbane gives her details as Mary Ann McCann, widow, however I’ve been unable to definitively identify a matching earlier marriage and subsequent death of a first husband. The most promising records relate to the 1842 marriage of Mary Ann Gorman to Patrick McCann in Melbourne and the death of a Patrick McCann in Sydney in the same year.

We know that Mary Ann was in Sydney in April 1843 from a newspaper report of the proceedings of the Sydney Police Court and the subsequent gaol admission register.

“Mary Connor and Mary Ann McCann, two of the ladies who had been in custody for eight days, on a charge of stealing a watch from a young man whom they had inveigled into their brothel, in an alley at the bottom of Jamison-street, were both committed“.

Mary was admitted to Darlinghurst Gaol, only to be released by proclamation some 3 months later. The sailor she was accused of robbing had left Australia, leaving the police with no witness.

We have numerous and at times contradictory descriptions of Mary from prison admission registers, including the one from this occasion. She was around 5’2″ (157mm) tall and slender. Mary was variously described as having a fresh or ruddy complexion, her hair brown, red or sandy and her eyes grey or hazel.

Moreton Bay

In February of 1844 Mary married George Williams at St. John’s Anglican church in Brisbane.

Brisbane was a very small remote settlement. The 1846 census recorded a European population of just 829, with 346 of these residing in South Brisbane. Some 40% were illiterate, including Mary who made her mark on the marriage certificate. There was a huge gender imbalance with just 30% female.

George Williams has also been difficult to trace. In 1843, he purchased a 36 perch (910 square metre) block of land in Grey Street, in partnership with James Moyes, for £23. There are later mentions of a George Williams in Ipswich and Dalby, but it is not an uncommon name.

The Brisbane police lock-up

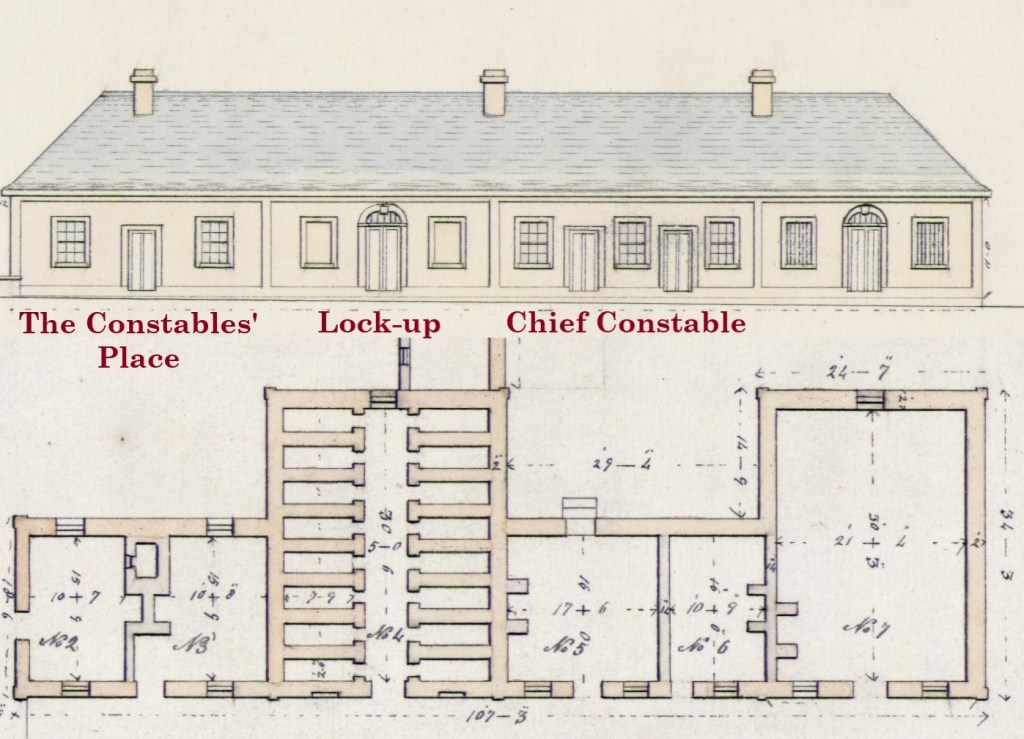

The Moreton Bay Courier was founded in June of 1846, and a few months later its report on the day’s proceedings in the Police Court mentions that Mary was arrested for being drunk and disorderly at South Brisbane. She was described as being ‘respectably dressed‘ but in the lock-up

“she conducted herself in a manner quite unbecoming her sex, and the Bench, to mark their sense of the impropriety of her conduct, sentenced her to pay a fine of fifteen shillings and costs.”

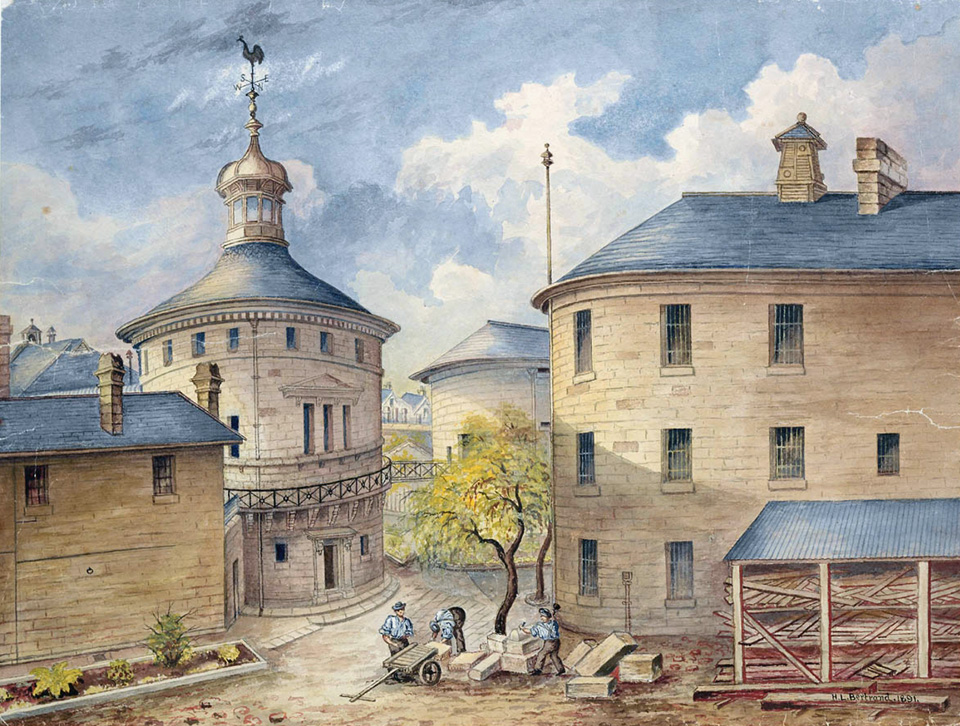

The lock-up utilised cells that had been built in 1828 to place offending convicts in solitary confinement. In 1847, it was described as “a dungeon indiscriminately used for the purposes of detention before trial and solitary confinement after conviction”. The dimensions of each cell were 7′ 9″ by 2′ 6″, or 2.4 metres long and just 760mm wide.

The Brisbane police and the colonial justice system

The “NSW Police in Town Act (Sydney)“ of 1833 created the position of Police Magistrate. A Police Magistrate was able to appoint police constables and their jurisdiction was defined by the Sydney town boundary. In 1838, a further Act extended the framework to other towns in NSW as required. Brisbane’s first Police Magistrate was John Wickham, who took up duty in 1843. The Brisbane town boundaries were surveyed in that year, but weren’t proclaimed until 1846, as described in my post “Vulture Street- From Dotted Line to Bitumen”.

Amongst other roles, a police constable was granted powers to arrest any drunk person in a public place or on the street at any hour of the day and

“all loose idle drunken or disorderly persons whom he shall find between sun-set and the hour of eight in the forenoon lying or loitering in any street highway yard or other place within the said towns and not giving a satisfactory account of themselves.”

The various police forces in the colony remained under the control of local Police Magistrates until 1851, when the role of Inspector General of Police was established in Sydney along with district Provincial Inspectors.

The Police Court, or Court of Petty Sessions, was headed by the Police Magistrate who was supported on the bench by a number of Justices of the Peace, acting as magistrates. They were usually drawn from the upper levels of colonial society. In 1840s Brisbane, for example, their number included wealthy squatter Francis Bigge, whose cousin Lord Stamfordham was private secretary to the Queen and John Balfour, also a squatter. Both were later appointed to Queensland’s new upper house of Parliament. Another was Brisbane’s doctor at the time of transition to free European settlement, David Keith Ballow.

Mary attended the Police Court when charged with being drunk and disorderly or using obscene language. At the time, in all convictions under the Police and Licencing Acts, “informants”, that is the police constables, were given half the fine collected by the Court. For this reason, the handful of constables in South Brisbane were motivated to arrest people like Mary, as it offered the likelihood of a healthy remuneration, at least as long as the fine could be paid.

In 1840, Governor Gipps proclaimed three Supreme Court districts “southern, western and northern ” each of which were to be visited twice a year. The Supreme Court on Circuit dealt with more serious cases. The first sitting in Brisbane was held in 1850 and presided by Judge Therry, who sentenced Mary at the October 1851 Brisbane Assizes to three months with hard labour for theft.

More problems

In September of 1847, in another reported appearance of Mary at the Police Court when she was fined a substantial 20 shillings, the writer commented that “her tippling propensities have made her a somewhat prominent character in Brisbane”.

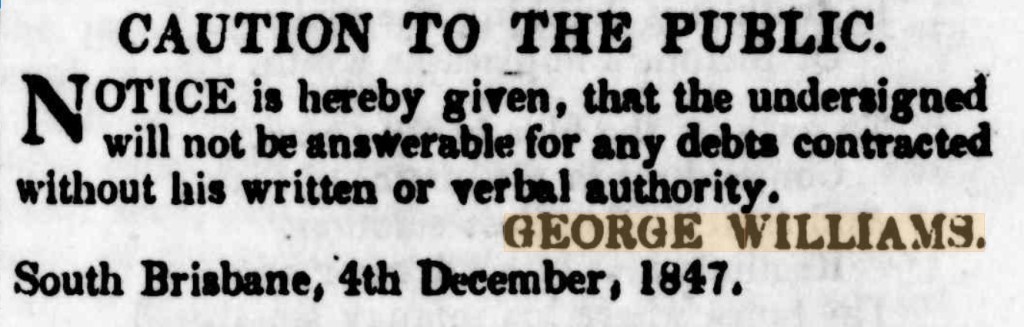

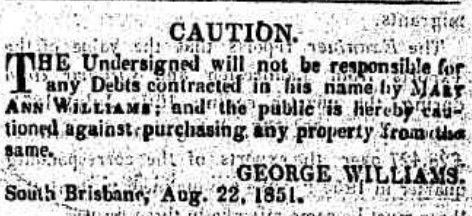

A few months later, her husband George placed an advertisement in the Moreton Bay Courier, warning that he wouldn’t be responsible for Mary’s debts, without actually naming her.

One can’t help but wonder if George and Mary were among the couples referred to by the journalist writing shortly afterwards.

“South Brisbane has long been notorious for the violence and frequency of matrimonial squabbles, scarcely a day or night passing without an exhibition as disgraceful to the parties immediately interested as it is annoying to the respectable portion of the inhabitants.”

The article goes on to describe two incidents occurring one evening in houses a few doors apart. In the first row between spouses, “one woman, who is a reproach to her sex, forgetful of all sense of decency and feminine decorum, indulged in language which would have disgraced the lowest inmates of St. Giles” (a workhouse in London noted for its primitive conditions), setting all the dogs off barking. In the other, after a long argument, the husband shouted out “I am an honest man; I am an industrious man; I am a hard-working man; I am a loving man” and then knocked his wife to the ground after which they retired to their house.

The trials of Mary

In 1848, Mary was brought to trial before the Magistrates’ Court for the usual offence of being drunk and disorderly. In an article headed “A Disorderly Character”, the journalist adopted the typical mocking tone of these types of reports at the time.

“The defendant had of late been rather given to truant wanderings and occasional fits of jollification at the public houses in South Brisbane, which were totally at variance with the vows she made when the conjugal knot was tied.”

Adding to the severity of the approach of the magistrates was her use of obscene language, described as “some of the choicest epithets culled from Billingsgate phraseology“. She was sentenced to two months imprisonment under the Vagrancy Act and taken to Sydney for a second spell at Darlinghurst, as there was no gaol in Brisbane.

Back in Brisbane there were more mentions of appearances in court.

On Monday night last, Mary Ann Williams, being thereto instigated by sundry nobblers and deeper potations indulged in during the day troubled the inhabitants of South Brisbane with an exhibition of her jovial qualities, by “flaring up” rather extensively in the public streets, in company with four or five gentlemen of her acquaintance.

The penalties were getting heavier – this time it was 21 shillings or 48 hours in the lock-up.

The Brisbane Gaol

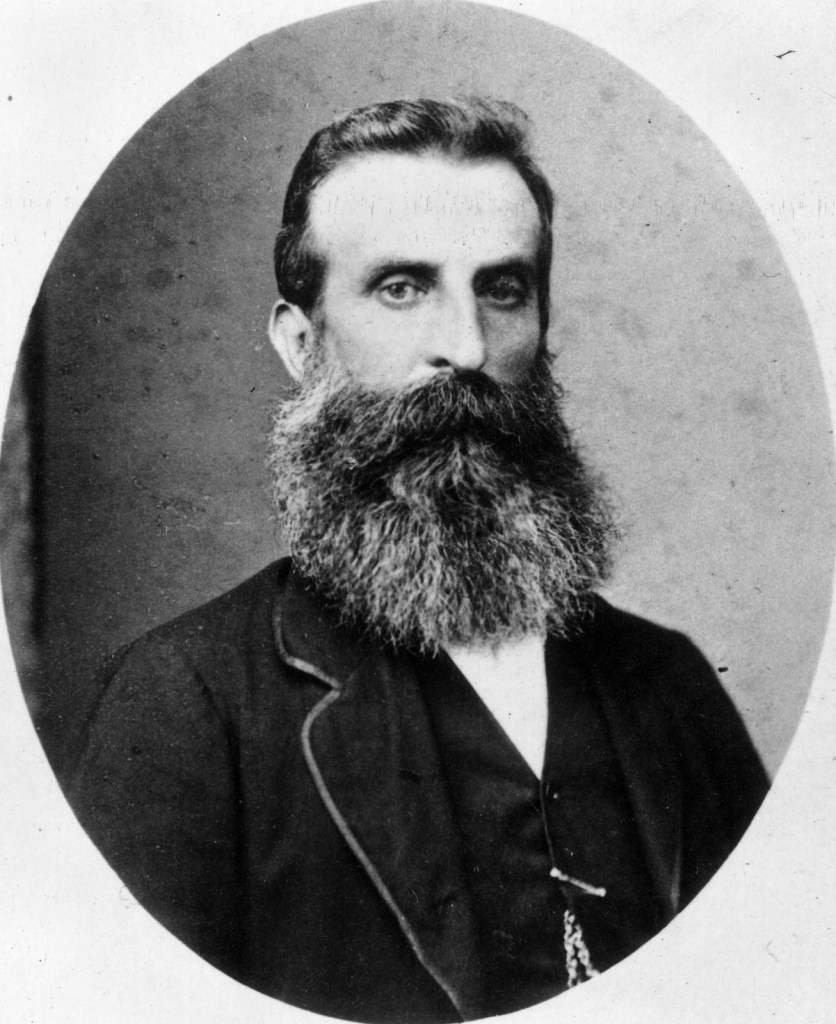

With no gaol in Brisbane, prisoners with longer sentences were sent to Sydney, as Mary had been in 1848. In 1846, the New South Wales Legislative Council had approved the expenditure of £820 to rectify the situation, but it was to be another 4 years before the prison opened, despite the high cost of transporting prisoners to Sydney in the meantime.

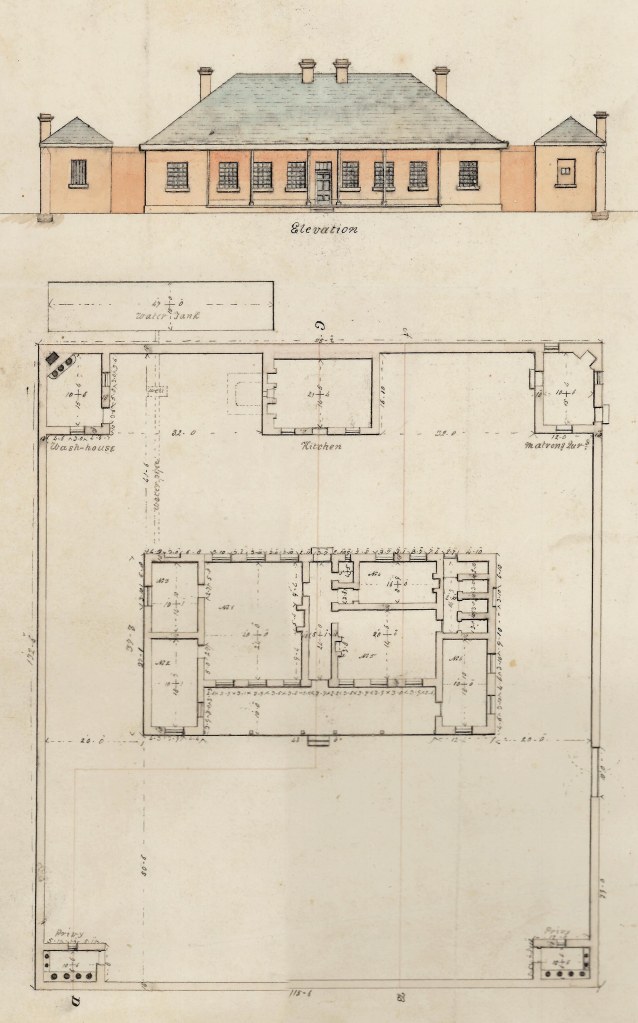

Captain Wickham decided that the best approach was to convert the Female Factory, where the Brisbane GPO was later built, into a prison. It was originally constructed in 1829 as the barracks for female convicts, but had not been used for that purpose since 1837.

The building was inadequate for its new role, being too small and in poor condition with crumbling brickwork. The gaol opened on the 1st of January and continued in operation until 1860, when a new purpose-built prison was inaugurated on Petrie Terrace. The space assigned to female prisoners was limited. In 1850, the first year of operation, 9 women including Mary appear in the registration records out of a total of 181 prisoners. One woman, Sarah Rutherford, was accompanied by two young children for her two days stay.

In July of 1850, Mary was being transported across the river from South Brisbane to the Queen Street lock-up. She jumped into the river and the two constables had some difficulty in getting her back into the dinghy.

Her sentence for drunkenness and obscene language on this occasion was £5 or three months. This was to be Mary’s first stretch in the new Brisbane Gaol, as she was unable to pay the £5 fine. After two weeks, it seems her husband George relented as the fine was paid, and she was released. Over the next two years, Mary was to spend a total of 7 months in this prison, with individual periods ranging from one day to 4 months.

From bad to worse

In 1851, George placed another advertisement in the newspaper this time naming Mary.

In October, Mary was in the lock-up, having been arrested for disorderly conduct. A constable heard a strange noise and found that Mary was attempting to strangle herself with a blanket wrapped around a bar of the cell. Doctor Swift (see my post All that glitters – Brisbane Gold Rushes) was called and copiously bled her. She was placed in a straitjacket. Later in the night, Mary pulled her arm out of the straitjacket and was found bleeding to death from where the doctor had used his lancet and she was taken to hospital.

A few days later, Mary was charged with having stolen a counterpane (bedspread) and net toilet cover from a neighbour, Mrs. Kirkwood. She had left the items with a Mrs. McCann, who had given them to Mary’s husband George who then returned them to their owner. Margaret McCann was a relative of Mary’s, who bought her tea, sugar and other items when she was in prison.

In November, Mary was sentenced at the Brisbane Circuit Court to 3 months hard labour to be served in Brisbane Gaol. Hard labour for female prisoners often meant long hours at the washtub.

It’s chilling to see that both the entries before and after Mary’s are for prisoners condemned to death. Moggy-Moggy, also known as Ohongalee, was an Aboriginal man accused of murdering a sawyer at Pine River four years previously. Although found guilty by the jury, the judge had misgivings over the key witness’s identification of the accused man after so long a time, and Moggy-Moggy was released on the authority of the Governor of NSW.

Angee was one of the many indentured Chinese workers brought to Moreton Bay to alleviate the shortage of labour. The overseer at the station where he had worked had been responsible for Angee serving a prison sentence for theft. He was sentenced to death for shooting the overseer dead in revenge after being released from prison. He was hung inside the prison walls, but in a location visible from Queen Street. The Moreton Bay Courier commented that

“the crowd assembled to witness the awful spectacle was not large, and we observed only one Chinaman; but, disgraceful to say, a large proportion consisted of women and children.”

Things come to a head

By early 1852, George had instigated legal action to formally separate from Mary and pay her an allowance.

In April, Mary was arrested for stealing linen that a neighbour had placed out to bleach on the grass. It was found at George’s house. He was out of town and Mary was staying there in his absence with a 6 year old girl whom she had adopted. Being unable to pay the 40 shilling fine, Mary was back in the Brisbane Gaol for a month.

Mary had only been back out of prison for a few weeks when she landed in serious trouble. Arrested for drunkenness, she told the police that she had seen local fisherman Tim Duffy coming out of the house of solicitor Robert Little with a watch and scent bottle. She said that she had seen Duffy put them in a hiding place. When the police were unable to find the items, she nominated another location where again nothing was found.

Mary then changed her story and said that Duffy had asked her to sell the watch and mentioned another location again in front of the hospital. Surprisingly, despite thinking that they were being made fools of, the police went there to search. This time they found the watch and bottle wrapped in a handkerchief which was proven to be Mary’s.

Duffy was arrested but after some investigation he was released and Mary charged in his place. It transpired that Mary knew the house as Little had organised the marital separation for George. At the Brisbane May Circuit Court hearings, the jury found Mary guilty of theft after hearing evidence from various witnesses.

Chief Justice Alfred Stephen’s summing up was lengthily reported in the Moreton Bay Courier. His sentencing was based not so much on the theft of a £5 watch and a bottle worth one penny, but more on her attempt to place the blame on Duffy. He was reported as saying:

“However she might have hoped to deceive people in this world, there was a God above her who knew -as she herself knew- her deep guilt and whom it would be in vain to attempt to deceive.”

He read out a list of her twenty convictions for drunkenness, obscene language, assaults, and robberies over the previous four years before sentencing her to three years with hard labour and the first fourteen days of each of the first four months to be passed in solitary confinement. Mary leaving the court “made some disgustingly offensive gestures to the police”.

Solitary confinement was usually accompanied by a diet of bread and water or half rations. For female prisoners, hard labour often meant long hours at the wash tub. It was a harsh sentence.

What happened next?

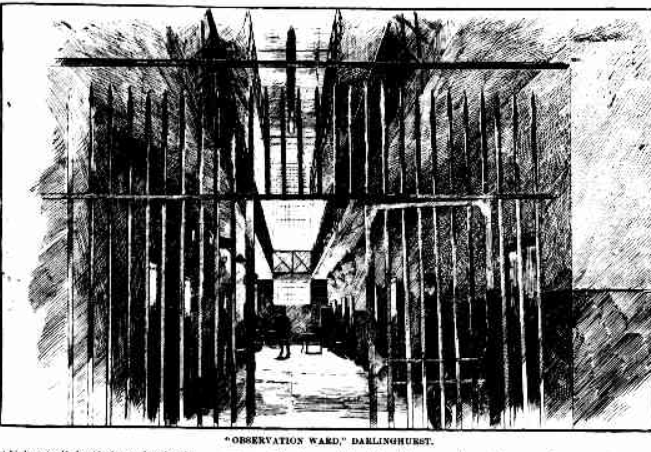

Mary was once again incarcerated in Darlinghurst Gaol. Brisbane Gaol utilised dormitories shared by prisoners of the same gender, whereas Darlinghurst was built to the “separate system”. This was based on the idea that moral rehabilitation would come from keeping prisoners isolated from others for at least part of their sentence or daily routine.

Darlinghurst allowed for the separation of prisoners into eight classes with separate individual cells. The women’s wing was built to hold 156, but would actually on occasion have over 400 female inmates.

Mary’s life after she was released in 1855 is difficult to trace. There is no further mention of her in the Brisbane newspapers so presumably she remained in Sydney.

There were several women with the same name who were mentioned from time to time in official records and newspapers. Some examples include the Mary Anne Williams who arrived as a convict in 1825 and was considered “useless at her work”, another who stole a policeman’s staff in 1853, the middle-aged Mary Anne Williams of “Humpty-dumpty” proportions who ended up in court for ” borrowing” an umbrella around the same time, and another woman of the same name who was given an 18 month sentence for theft in 1855.

Perhaps it was our Mary Anne Williams who, freshly released from Darlinghurst, was sentenced to 48 hours jail in May of 1855 for singing an obscene song in Durand’s Alley. It was an infamous “rookery” known as “the haunt of layabouts and whores“.

(Sydney Illustrated News, 2nd. August 1873)

With little known of Mary’s early life, it’s difficult to speculate on the reasons for her behaviour during the time she spent in South Brisbane. However, it could only have been exacerbated and reinforced by the male dominated legal structures of the time, and the harsh judgement passed on women who strayed from what was considered acceptable social behavior.

References

Most references appear as hot links in the text.

Register of male and female prisoners admitted – HM Gaol, Brisbane

© P. Granville 2023

Thanks Paul. What a fascinating yarn. Certainly brings history alive. I admire your tenacity.

Liz xx

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Liz. Researching the 1840s period is quite daunting!

LikeLike

Enjoyed reading the “biography” of Mary Williams

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks

LikeLike